Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

It used to be you had to go either to Ireland or the Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City to find records of your Irish forebears. The FHL is still the country’s best one-stop shopping mall for Irish records. It has the largest Irish records collection in America, with more than 11,500 microfilms and 3,000 microfiche, plus extensive map resources, handbooks, directories and more than 3,500 reference books and periodicals covering Irish history, genealogy, geography and more. If you can swing it, a trip to the FHL is worth it for no-wait access to all those records and the non-circulating printed material.

But nowadays, you can access even the following less-obvious sources via online collections of indexes and record images, or by visiting your local Family History Library. Start singing the words of the old tune, “Did your mother come from Ireland? ‘Cos there’s something in you Irish,” because we’re about to share online and offline resources for six often-overlooked paths that will lead you to your Irish roots.

1. Irish Family History Foundation

An online database called RootsIreland.ie connects you to Irish counties’ genealogy centers, which hold local records such as transcripts of parish registers. The nonprofit Irish Family History Foundation (IFHF) operates the website and genealogy centers with a goal to create a mega-database of Irish records from local historical societies, clergy, civil authorities, county libraries and government agencies.

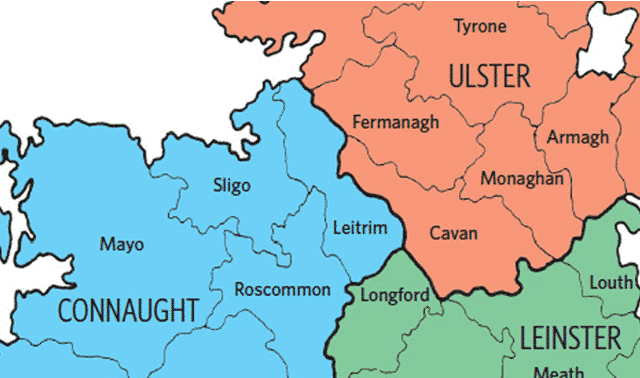

The site currently has extracts from more than 18 million records: baptismal and birth records, marriage records, burial and death records, census records, gravestone inscriptions, passenger lists, and Griffith’s Valuation of Rateable Property (an annual property valuation published between 1847 and 1864). When you visit the home page, click the map of Ireland on the right. Color coding tells you which counties have records online: Only a few areas—a pocket in Dublin and counties Clare, Carlow, Kerry and south Cork—haven’t yet put their records on the site.

Click a county to see available indexes, or use the dropdown menu. You can search indexes for free, though you’ll need to register for an account. The database points you to record abstracts (not the original records).

2. Surviving 1841 and 1851 census records

Most of the 1841 and 1851 Irish census, along with all known records of other 19th century enumerations, were destroyed during the Irish Civil War of 1922 when a fire broke out in Dublin’s Four Courts building. Only the 1841 enumeration of the parish of Killeshandra in County Cavan survived.

But here’s some good news: During the 1910s, Irish clerks used the 1841 and 1851 censuses to prove age on Old Age Pension applications. They searched census returns and recorded what they found on pension forms. Even if your ancestor left Ireland before the 1910s, one of his family members who stayed behind might have applied for an Old Age Pension. The forms provide the applicant’s address at the time he applied, names of the applicant’s parents (including the mother’s maiden name), and the applicant’s address in 1841 or 1851 (county, barony, parish, townland, and street if in a town). Some pension clerks even recorded the names and ages of everyone in the census household, so it’s worth a look even if your ancestor was one of those pre-1910 immigrants.

The original pension forms are at the National Archives of Ireland and the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (for counties now in Northern Ireland). Pension records for Northern Ireland and County Donegal also are online at Ireland Genealogy, where you can pay about $3.30 per record view.

For both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, the pension forms also are on FHL microfilm. To find which roll you need, go to the online catalog and do a Place search on Ireland, then select either Census—1841 or Census—1851. Look for “Census search forms for the 1841-1851 censuses of Ireland.” The indexes and forms are arranged by county, then barony, parish, and townland. First look for your ancestor in the index, which will tell you from which census the form was compiled. Copy the reference number from the index, as this is what you’ll need to find the form on microfilm. You can rent the film by visiting your local FamilySearch Center.

3. Prison records

Harsh times called for harsh measures, and many of our Famine-era ancestors were arrested for crimes such as stealing from a neighbor’s garden. From 1790 to 1924, drunkenness accounted for more than 30 percent of crimes reported and more than 25 percent of incarcerations, according to prison registers on subscription site FindMyPast. Considering that more than 3.5 million names (prisoners, as well as relatives and victims) are listed in the records when the Irish population averaged 4.08 million, the odds are good you might find a relative.

By 1822, Ireland was home to 178 prisons. FindMyPast.ie’s Irish Prison Registers 1790-1924 collection covers a variety of institutions, from county prisons to sanatoriums for alcoholics. Many of the transgressions were minor, such as being “idle” or “a suspicious character.” The registers give details such as the prisoner’s name, address, place of birth, occupation, religion, education, age, physical description, next of kin, crime committed, sentence, and dates of committal and release (or death date).

You can access the collection on FindMyPast.ie with a subscription or with Pay As You Go credits. Go to the Search tab, then click on Courts & Legal. Keep in mind that a county search on this site checks the county where the prison is located, not necessarily the county of birth or where your ancestor lived. The original prison registers are at the National Archives of Ireland in Dublin.

4. National School records

Irish National School records cover from 1831, when National Schools were established, through 1921. School registers typically give the name and age of the pupil, religion, father’s address and occupation, and general observations about the student. Some may record the student’s birth date, attendance, grades, and when the pupil left the school.

Although most school registers are still in the custody of the local school or church, the National Archives of Ireland has them for about 145 schools in counties now in the Republic of Ireland. They date primarily from the 1870s and 1880s. The FHL has some of these registers on microfilm. To see if any might cover your ancestor’s school, run a place search on the county (or city), then look for the subject heading of Schools.

The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland’s school records collection is much more substantial for the six Northern Ireland counties. That repository has more than 1,500 registers, most dating from the 1860s onward, though some date from the 1850s. Better yet, the FHL has these on 80 rolls of microfilm. Run a Place search of the online catalog on Ireland, then look for the subject category Schools. From there, look for “National school registers of North Ireland, 1850-1950: Down, Londonderry, Antrim, Armagh, Fermanagh, and Tyrone counties.”

Then it gets messier: The records are cataloged by the name or location of the school. It might take searching through several registers for an area to find the school your ancestor attended. Additionally, there might be two registers for each school, one for female pupils and one for male pupils. Consult the finding aid “Descriptive Catalogue of Pre-1900 School Registers,” on eight rolls of microfilm, which includes an alphabetical index of schools.

5. Land records

Starting in 1708, land transactions were recorded with the Registry of Deeds in Dublin. This wasn’t mandatory, so not all transactions were registered, but in these records you’ll find deeds of sale, lease agreements, marriage settlements, and wills.

Most likely, your ancestors didn’t own land in Ireland, but that doesn’t mean land records won’t be valuable to your search. Many of our poor rural ancestors leased their small plots of land and cottages, and some leases were recorded among the land records. A common type of lease was a “lease for lives.” This meant the persons named in the lease held the land for as long as someone named in the lease was still alive. Once no one on the lease was still living, the lease ended. The lease usually named three people—often a father, one of his sons, and the youngest son, who presumably would be the longest-surviving tenant.

Leases could also be granted for a certain number of years, or land could be rented on an annual basis without a lease. I found the lease with my great-grandfather, David Norris, as the leaseholder, along with the amount of rent, after his father and older brother died.

After 1782, when some Penal Laws were relaxed against Catholics and dissenting Protestants, tenants could purchase land outright or “in fee.” It might have taken several generations, though, for a family to save enough to purchase the land on which their homes stood. In the late 19th century, the government set up schemes to assist tenants in purchasing the property they leased.

The FHL has microfilmed indexes and deeds (1708-1928) from the Registry of Deeds for all of Ireland. In the library catalog, run a Place search on Ireland and look for the subject heading Land and Property. Then scroll down until you find “Transcripts of memorials of deeds, conveyances and wills, 1708-1929.” The alphabetically arranged Surname Index includes only grantors (sellers). The grantor’s name is followed by the grantee’s (buyer’s) name, county, year, volume number, and deed number. There’s no index to grantees.

It’s easier to search the Land Index, which is arranged by county and barony. Look for all entries for your ancestor’s townland (they won’t necessarily be together or in any particular order). This index gives the parish, grantor, grantee, year, volume and deed number. After finding entries for the townland, search the column for grantees’ names in that townland. You’ll probably need to search many rolls of indexes; each index might cover only a five-year time span. If you find your ancestor in the index, look for the deed in the corresponding microfilm with that year and deed volume.

6. Wills and administrations

Most people in Ireland were too poor to leave wills, but don’t make assumptions about your ancestors. Just as with land records, it’s better to check a source and find nothing, than to assume your family isn’t in the records. I didn’t think any of my ancestors had anything of value to warrant a will, yet I found one for my great-great-grandfather John Norris of Tamlaghtmore, County Tyrone, who died in 1898. Even though he didn’t own land, he did own farming equipment.

Wills can be divided into pre-1858 and post-1858. The jurisdiction for keeping wills and administrations changed in 1858. Before, the Church of Ireland recorded these documents and transferred records older than 20 years to the Public Record Office in Dublin. Unfortunately, the records were destroyed in the Four Courts Fire. A good number of the church’s indexes survived, however, as well as some abstracts. And don’t forget to check the aforementioned Registry of Deeds, as some wills were recorded there.

After 1858, all probates and administrations were recorded at the Principal Registry in Dublin and at eleven District Registries throughout the country: Armagh, Ballina, Belfast, Cavan, Cork, Kilkenny, Limerick, Londonderry, Mullingar, Tuam and Waterford. Each Registry includes several counties. County Tyrone, for example, is part of the Armagh Registry. For a list of counties within the districts, scroll down to the Districts subhead. Original wills between 1858 and 1900 also were destroyed in the fire, but you can find transcribed copies from the 11 District Registries. Wills since 1904 are intact for all 12 registries.

If your ancestors were from Northern Ireland, you can search an index to the will calendar entries for the three District Probate Registries of Armagh, Belfast and Londonderry on the Public Record Office (PRONI) website (click Will Calendars on the right). Calendars were published annually starting in 1858 and contain abstracts of wills and administrations. The calendars are arranged alphabetically by surname and can contain the name of the deceased, address, occupation, date of death, date of probate, whether a will or an administration (meaning no will, but sufficient enough estate to enter into probate) was filed, names and relationships of next of kin, value of the estate, and the registry in which the will was proven. PRONI’s database covers 1858 to 1919 and 1922 to 1943. Part of 1921 has been added, with remaining entries for 1920 to 1921 still to follow. The index links to digitized images from the copy will books for 1858 to 1900, some 93,000-plus images. And it’s all free.

The National Archives of Ireland is trying to reconstruct lost wills of the Republic of Ireland by using abstracts and requesting copies from families and attorneys. Consequently, it now has thousands of testamentary records you can search in the Irish Wills Index at subscription site IrishOrigins.com. It covers only up to 1858, however.

You can find copies of surviving wills and administrations for the eleven District Registries on FHL microfilm. These can be difficult to find and use. In the online catalog, check under Ireland—Probate records, and also under Ireland—Probate records—Inventories, registers, catalogs. If you’re at the library in Salt Lake City, look for the Irish Probates Register. It’s easier to find the correct film using this guide than the catalog.

Another FHL microfilm source to check is “Calendar of the grants of probate and letters of administration made in the principal registry and in the several district registries, 1858-1920.” Find these microfilms in the FHL catalog by searching under Ireland—Probate Records—Indexes.

Whether it’s your mother, grandmother or some other relative who came from Ireland, ‘tis a grand time to be an Irish genealogist. These often-overlooked sources and databases will help you find that “something in you Irish.”

Tip: Two free searchable resources for tracing Irish ancestors include the National Archives of Ireland’s 1901 and 1911 censuses and AskAboutIreland’s Griffith’s Valuation.

Tip: Records generated when an Irish immigrant died may reveal his place of origin in Ireland. Check death certificates, cemetery registers, tombstones, church burial records, obituaries, funeral home records and funeral cards.

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2012 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT