Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Imagine someone showing up at your American ancestors’ door every 10 years and taking a group photo of the household. You’d want all of those pictures, wouldn’t you? They’d show a time-lapse biography of your family. You’d study each person’s age progression, how hairstyles and fashions changed, who appeared or disappeared (and when) and how the backdrop changed over time.

The US census is that decade-by-decade picture—albeit in words. Every decade, census-takers compiled a list of nearly all American households. As time went on, they gathered slightly different—but increasingly more—information. By the late 1800s, censuses could tell us who lived with whom and how they were related, how well they lived, what work they did, and sometimes when or where they were born, married and died.

Censuses are so data-rich that they’re among the first places you should look for your family history—and you should keep coming back to them. It’s difficult to absorb everything on the first pass. Revisit your ancestors in censuses to find clues you missed, interpret new finds or confirm you’re on the right track.

We’ll show you what’s in census records, how to find your ancestors’ records, and how to extract every possible clue.

Census Record Coverage

The US Constitution calls for a nationwide population tally every 10 years for congressional-representation purposes. The first was in 1790; the most recent was in 2020. Additionally, the federal government picked up part of the tab for an 1885 census of some states and territories, so that counts as a federal census, too.

Census-takers were to visit each household. It might have taken weeks or months to visit everyone, but all information collected was supposed to reflect the household as it was on a specific date. The official census date (see a list of official US census dates) is important when you’re calculating household members’ birth years based on the age in a census, or if someone was born or died around the time a census was taken.

Over time, standardized questions, census forms and procedures developed. Enumerators received instructions about the direction to proceed around neighborhoods, the intent behind questions and how to code a variety of answers. For some censuses (see below), enumerators asked a set of supplemental questions of those in certain population segments, such as veterans or those with disabilities, to capture social, economic and public health information.

Details in Census Records

Genealogists might cluster US censuses into three groups: the least informative (1790–1840), the fairly informative (1850–1870) and the most informative (1880–1950).

1790–1840

These early censuses name only heads of household, and count others. The 1830 census was the first to use a standard preprinted form. Here’s a breakdown:

- 1790–1810: names the head of household with tallies of other household members by age group, gender, race (white, black or Indian), and free or slave status

- 1820: same as above, plus tallies of aliens and workers in agriculture, commerce and manufacture

- 1830: drops the industrial categories and added tallies of the deaf, “dumb” and blind, segregated by race and age

- 1840: reintroduces employment tallies for various industries; adds military veterans receiving pensions; and tallies those in school, illiterate white adults, and “insane” and “idiots” cared for at public expense

1850–1870

Beginning in 1850, every free household member was named, and homes and families were numbered in order of visitation.

- 1850: name, age, sex and color of each free person; value of real estate owned; place of birth; whether married or attended school within the year; whether an illiterate adult or “deaf and dumb, blind, insane, idiotic, pauper or convict;” and occupation of males over 16

- 1860: adds value of personal property

- 1870: adds more-detailed age, race and literacy descriptors. This census adds indicators for parents of foreign birth; month of birth or marriage if occurring within the year; voter eligibility; and whether a victim of voter discrimination. Names the formerly enslaved for the first time.

1880–1950

Beginning in 1880, the level of family history detail in the census rises to a new high. Home addresses, family relationships, and more put these among the richest existing sources for American genealogy:

- 1880: adds street address, relationship of each person to head of household, marital status, everyone’s profession, months unemployed, illness or disability on date of visit, parents’ birthplaces

- 1890: adds more-detailed capture of race, household structure, naturalization status and disability/illness; number of children borne/living and years in the United States; months attending school; parents’ birthplaces; whether a homeless child, convict, prisoner or Civil War veteran/widow; native tongue (if not English). Sadly, all but a handful of schedules for this census were ruined after a fire.

- 1900: removes native tongue, adds month and year of birth, whether an English speaker, years in present marriage, year of immigration/number of years in the United States, homeownership/renter status.

- 1910: removes birth month and year, adds occupational and unemployment details, Civil War veteran status, and language of non-English speakers. Less detail requested on schooling and disability.

- 1920: removes childbearing data, adds year of naturalization, mother tongue for self and both parents, whether living on a farm

- 1930: adds value of home/rental, radio ownership, age at first marriage, mother tongue of foreign born, English language ability, unemployment, military veterans mobilized (and for which war)

- 1940: adds informant to the census taker; highest school grade completed; place of residence on April 1, 1935; and details on employment status, occupation, involvement in public emergency work, income amount and source.

- 1950: asks for many of the same details as 1940, but relegates questions about education to only a subset of respondents.

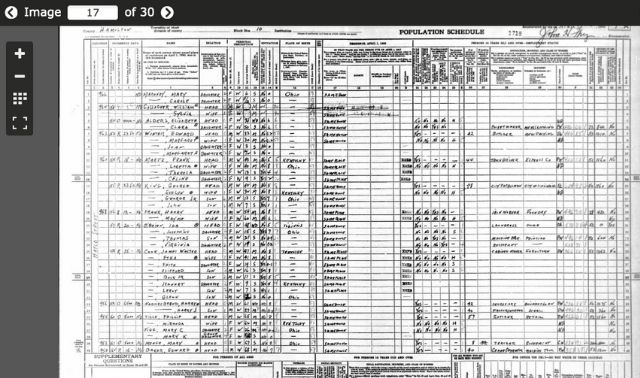

Sample Records

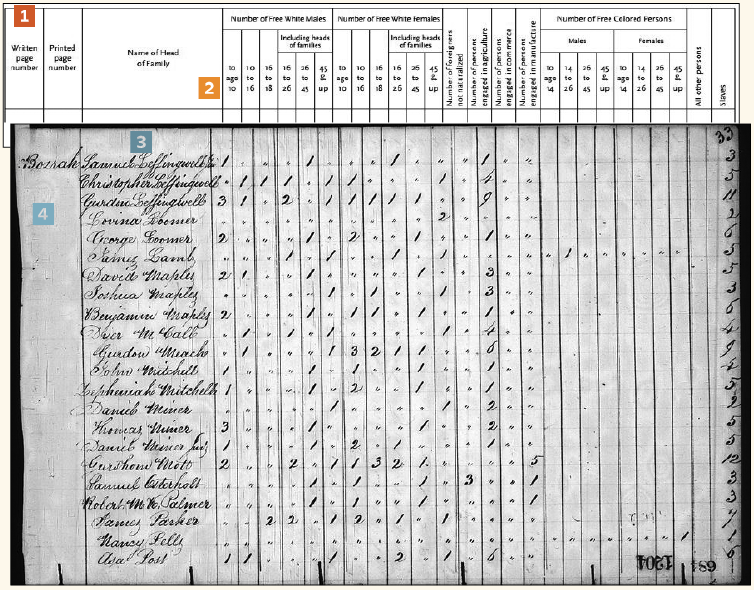

1820 Census

- The earliest censuses didn’t use preprinted forms. This page doesn’t have column headers. Using a blank census form, as shown here, makes the census easier to read.

- Without a preprinted form, missing columns are possible. When you extract data onto a blank census form, note any missing columns and take this into account when interpreting data.

- Only head-of-household names appear in this census. Use the tally marks to identify likely household members based on what you know from later censuses and other sources. Remember, not all may be relatives.

- This list is in alphabetical (not household) order, a rearrangement occasionally done by early census takers. This makes it easier to spot others of the same surname. If you’re looking for the neighbors, check maps, land records and other sources that would show who lived where.

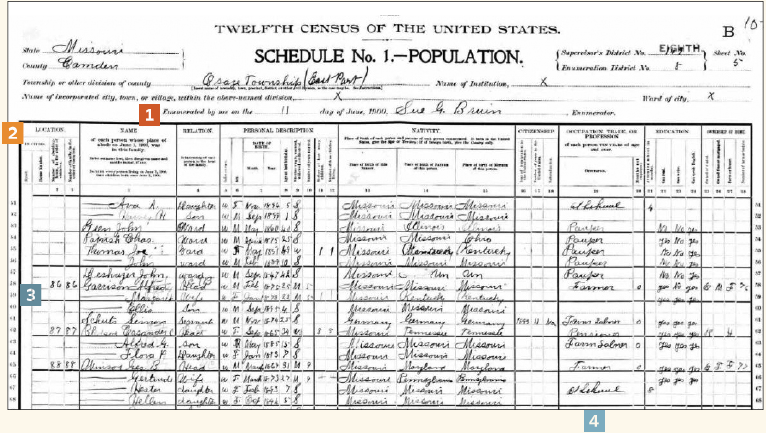

1900 Census

- Note the actual date the census was taken—June 11. The information recorded should reflect the official census date, June 1, but sometimes births or deaths occurring in the interim weren’t accurately logged.

- Later censuses like this one collected a variety of data. This one requests birth month, year and place for household members, and birthplaces of their parents. Extract all the information (including what you already knew) onto a blank census form.

- Households are numbered in the order the census taker visited them. Browse through a few pages for familiar names and neighborhood makeup, such as a dominant ethnicity and common occupations.

- The occupation column may include nonworking terms such as at school (for students), pauper, pensioner and at home (for homemakers). These clues may point you to school, poor relief, pension and other records.

How to Access and Use Censuses

Original and microfilmed population schedules are at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), but most originals are closed to researchers. It’s easier to find relatives by searching digitized, indexed versions of decennial censuses at major genealogy websites. Online versions of the 1885 population censuses for most or all of Colorado, Florida and Nebraska, and the territories of Dakota and New Mexico, are at Ancestry.com.

Per privacy laws, US censuses are restricted from public view for 72 years. As a result, the 1950 census is the most-recent available for research as of writing. The next, the 1960 census, will be released in April 2032.

Search tips

Try to locate each relative in every census taken during that person’s life. Begin with the most recent census in which someone should appear and work back through time (then forward, to help verify your death date for the person). You’ll be able to track migrations and note slightly (or widely) different answers to similar questions over the years—even for categories you’d expect to be consistent, such as age. You might discover surprises and detours in relatives’ lives.

Search first by the person’s name. If needed, use the site’s filters to narrow your search to a specific census and location (state, county or town). Restrict your results to see just census records. (There’s usually a filter called something like “restrict by record type.”) Then broaden the location if you can’t find the person.

Census takers didn’t ask people how to spell their names, so misspellings are common. In addition, indexers may have made errors when transcribing the names to create searchable indexes. To overcome these problems, try spelling variations, nicknames, different combinations of first and middle names and initials, and both maiden and married names for women. If the site allows it, you can leave out the name and search on other variables. Keep track of your searches in the Online Database Search Tracker.

Still can’t find someone? Browse the census in a probable location. You can do this on several genealogy data websites. Beginning in 1880, you may need to know the enumeration district (ED) as well as the town or county to browse by location (the city of Chicago alone has nearly 200 EDs in 1880). One-Step Webpages by Stephen P. Morse offers several tools for finding EDs; on the home page, scroll to the US Census section.

Your ancestor might simply not appear in a given census. At times, the census missed people. And almost all of 1890 census was destroyed in a fire; lost, too, were significant portions of the 1790 through 1810 censuses. In such cases, look to census substitutes—records created around the same time with similar information. These include state censuses, tax records, school censuses, voter lists and other local enumerations. Consult state and local genealogical guides for availability.

Censuses often contain clues to extended family. The easiest way to jump back a generation is to find an aging parent living with an adult child. Use the head-of-household column to confirm the relationship. Remember that a “mother-in-law” is the head-of-household’s mother-in-law, not the spouse’s. Other strategies include:

- For 1850 or later, look for your relative as a young person in a parent’s household. You’ll be more confident you’ve got a match if your ancestor had an unusual name, if the family lived in the same neighborhood, the birth years match, and/or there’s only one reasonable search result. But treat these findings as circumstantial evidence and seek other sources for the parents’ identities.

- Use non-census records to identify parents: birth, marriage and death records; Social Security applications (SS-5); draft registrations, military service or pension paperwork and more. In city directories, an adult child might have the same residential address as the suspected parents. Once you identify the parents, return to the census and look for them.

- Browse census pages before and after your family’s listing for relatives who live nearby. Do additional research to reveal how these folks might be related.

Documenting census details

As you move across time through censuses, a household picture emerges. A single person marries, children are born and leave home, relatives move in or out, spouses die, a widower remarries. Keep track of all this data properly, and you’ll make a lot better sense of it.

Every time you find a family member in a census, attach the source information to the individual’s profile in your online family tree and/or cite it in your family tree software. Save the record image, too. (You could use a photo editor to add source information right on the document.) If you’re paper-based, print the census image, jot the source information on it, and keep it in that family’s file.

Next, extract every piece of data you find, even if you think you’ll remember it or it doesn’t seem valuable. Census worksheets give you handy blank census forms to copy in your ancestors’ stats under preprinted column headers.

Pay special attention to the “relationship to head of household” column that first appears in 1880. The head of household (usually a man) is designated on the census. Keep in mind that person’s child may not also be the spouse’s child.

You also can use the Census Record Extraction form to create an at-a-glance summary of several types of census data (most useful beginning in 1850). Remember: The same information may be requested in different ways in each census, and even presumably “unchanging” information like birth year may be reported differently over time. The two reports of the same data are valuable, so log each year’s statement for each category.

Errors and inconsistencies in censuses

Note that it’s not uncommon to find someone whose age “changes” by more or less than the expected amount from one census to another (e.g., 22 in one census, then 30 ten years later, then 39 ten years after that). Before birth certificates and Social Security, many people didn’t know or care exactly when they were born. Others misrepresented ages to enroll in the military or marry, and may have kept up the lie. Officials didn’t have a way to double-check for accuracy.

Discrepancies may show up for other reasons. The census taker’s source of information may have been a child or neighbor. Language barriers and cultural prejudices could result in miscommunication and inaccurate write-ups. Mistrust of the government may have led to lies, particularly about income or naturalization status. Someone wishing to hide a former marriage or childbirth might not report these events. Consider which of these reasons might best apply in your ancestor’s case and look for other records to confirm your suspicions.

Using Special Censuses

Several decennial population censuses included schedules for segments of the population, such as military veterans, the enslaved, the disabled, owners of farms or manufacturing businesses of a certain size, and the recently dead. These special “nonpopulation” censuses are available on microfilm and often, on the same genealogy websites as population censuses.

Here are the most-prominent, and what you can expect to find in them:

Agricultural schedules (1850–1880): These list farm owners or managers, acreage, cash value, crops and other products, livestock number and value, and value of homemade goods. Schedules were also created in years outside of this range, but those records are no longer available.

DDD Supplemental Schedule (1880): If the 1880 population census designated any relatives as sick, disabled (either physically or mentally), impoverished, homeless or a prisoner, look for them in the Schedules of Defective, Dependent and Delinquent (DDD) Classes.

Manufacturer/Industry Schedules (1810–1820, 1850–1880): Records from 1810 are largely lost. Reports for 1820 and 1850 through 1880 exist for manufacturers producing at least $500 annually in goods. These contain the name, business/product type, investment amount, values of raw materials and machinery, annual production, number of employees and labor costs.

Mortality Schedules (1850–1880, 1885): During each census, deaths from the previous June 1 to May 31 were logged with the deceased’s gender, age, color, widow(er) status, birthplace, death month, occupation, cause of death and length of illness. The 1870 and 1880 enumerations add more detail.

Social Statistics (1850–1880): These list no names, but they do list churches, cemeteries, fraternal organizations, clubs, schools, libraries, newspapers and other organizations in your ancestors’ communities.

Slave Schedules (1850–1860): These censuses name enslavers, but generally identify the enslaved only by age, sex, color (Black or “mulatto”) and whether a fugitive or manumitted. Use other sources to confirm a possible match for an enslaved ancestor.

Veterans Schedules (1840, 1890): The 1890 census listed Civil War Union veterans and their widows, plus some Confederate veterans. Schedules survive for half of Kentucky and the states alphabetically following it, plus Indian Territories and US ships and navy yards.

Census Record Fast Facts

- First U.S. federal census: 1790

- Frequency: every 10 years, plus 1885 for some areas

- Latest census available: 1950

- Next census available: 1960, scheduled for release April 1, 2032

- Significant missing data in: 1790-1810, 1890

- Location of original records: National Archives and records Administration

- Research online at: Ancestry.com, FamilySearch, Findmypast, MyHeritage

- Search terms: US census [insert year], federal census records [year]

- Alternate or substitute records: State and local censuses, tax records, voter registrations, city directories, Sanford maps (for neighborhood layout). Ancestry.com has census substitute databases for 1890 and 1950.

Version of this article appeared in the July/August 2014 and March/April 2023 issues of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT