Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Family history is full of surprises — just ask the folks who’ve brought their family’s treasures to be appraised on PBS’ Antiques Roadshow. One woman’s great-aunt left behind a ruby bracelet that a Roadshow expert valued at $165,000. Another appraiser judged a sampler made in Monture County, Pa., in 1838 to be worth $40,000 because of its excellent condition. A Boston highboy passed on through nine generations was priced at $50,000.

These are just a few of the discoveries from PBS’ most-watched series, which begins its fifth season in January. The show travels from city to city “in search of America’s hidden treasures.” Experts identify antiques brought in by everyday people, explain how much those items might fetch at auction and why — the Boston highboy would be worth twice as much if its original finish hadn’t been removed, for example.

But identifying heirlooms can also tell you something about your family: Who made this object? When and where did it come from? Is it typical or unusual for its time period? And that’s what most guests on Antiques Roadshow — who invariably say they aren’t going to sell their treasures — are really interested in.

So haul those heirlooms out of hiding. Let Antiques Roadshow give you a primer on 10 common types of antiques and tips to help you learn what your relatives left behind.

Furniture

The US government legally defines an antique as any object 100 years old or older. So if the chairs, beds and dressers passed down through your family are less than 100 years old, they’re considered used. Just because a piece is antique, however, doesn’t necessarily mean it’s highly valuable. Reproductions, for example, have only moderate value even if they were made more than a century ago.

The pinnacle of the antiques pyramid is period furniture: made when the design was first popular and new, and generally the most valuable. Period furniture may be of mediocre quality, but it’s always a legitimate product of its time.

How do you know if a piece of furniture is antique? Look for the these signs:

• Wear: Run your fingers underneath or over the back of the piece. Sharp edges can indicate recent manufacture.

• Irregularity: Before the 1840s and the Industrial Era, furniture never had machine-made parts. Look for hand-hewn undersides, uneven veneers and irregular widths between screw threads. Circular saw marks, plywood, staples and uniform dovetails (the “teeth” that hold wood joints together) are sure signs of modern construction.

• Color: Old furniture has either acquired a rich, deep color or it has faded.

• Form: Certain designs were typical only in certain periods.

Even more important than age is quality. The piece we value today is always crafted of rare or beautiful woods or cased in beautifully matched veneers. Carving is highly sculptural, with every detail crisp.

Silver

Pick up a silver spoon, tray or creamer and turn it over. Is the back or bottom impressed with the name of the maker, odd-looking symbols, or the word sterling? If not — if it’s stamped EPNS instead — you know two important things about it: It isn’t old. And it isn’t silver.

It may look like silver, polish like silver, even have a firm place in your family’s history as being silver — but it’s unquestionably Electro-Plated-Nickel-Silver. Base metal, unfortunately, beneath a silvery skin.

Silver was infinitely recyclable, which made fraud a lot easier. So England established a legal silver standard in the 14th century, requiring 925 parts silver in 1,000 parts of metal (pure silver is too soft to be useful). A symbol called a hallmark also had to be punched into each piece attesting to its silver content. So it’s not difficult to identify authentic silver because it comes to you impressed with useful information, such as the “maker’s mark,” or when and where it was made. All you need is a hallmark book to track the “footprints” that silver-smiths left behind — and perhaps find clues about the family members who owned it.

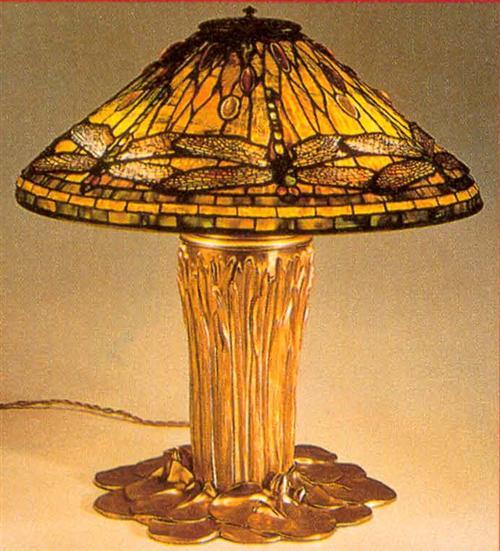

Common household objects such as furniture, dishes and lamps may be revealing their history — if you know how to look for it. The design and form of this pair of English chairs (left), this Queen Anne highboy and Windsor chair can indicate when and where they were made — some styles are typical of a particular era. Blue-and-white porcelain is common in many countries; look for a mark on the piece that will help you identify its date and place of origin. Because Tiffany lamps were so successful, they inspired many competitors. Check the lampshade — most genuine Tiffanys bear a marked copper label.

Porcelain, Pottery and Glass

When you turn over a plate or glass, you’ll often find marks — the factory name, a pattern name, a country of origin or some not-too-cryptic symbol. That’s good news if you’ve got ceramics or glassware you want to identify. Reference books list thousands of marks that, properly deciphered, tell how old a piece is, where it was made and whether it’s rare. In this realm, you’re most likely to stumble across European or American 18th- or 19th-century wares.

- Porcelain and pottery: Porcelain design tended to imitate the valuable silver of its own era, so a general silver book can help you recognize the shapes common to each design period and enable you to readily date those ceramics. Pay attention to condition and quality; ornamental objects are usually more valuable than cups and saucers.

- Class and crystal: Here’s one category where age isn’t important (glass doesn’t reveal its age, anyway). Value increases if a piece is rare or unusual — the most expensive pieces are one of a kind. Don’t get high hopes for Grandmother’s jelly glasses, stemware, tableware, cut glass or carnival glass — they’re too common to have unusual value.

Paintings

Many of the paintings we find, buy or inherit look “old.” But are they? You can begin to determine a painting’s age by examining the following features:

- Support: The flat surface that holds the paint, such as canvas, wood panel or paper. Canvas is usually a piece of linen primed with a coat of gesso to keep it from absorbing the paint, then pulled tight over a wooden frame (stretcher) and nailed to the back. In pre-industrial times, linen was hand-woven. Look for uneven weaving and lumpy raised threads, as well as darkening from age.

- Stretchers: Their wood should be age-darkened and have soft edges. Old stretchers sometimes have more than one set of nail holes (a sign of re-use or relining) and often have writing on them.

Next you need to determine if the painting is legitimate — that is, do the details on the front match the time when it was supposedly painted? (Only an expert can verify authenticity.) Be on the lookout for anachronisms in the subject (you should never find an 18th-century painting of a steamboat, for example), dates and technique. Carefully examine the signature. Artists sometimes used a symbol, or added words such as fecit (made by), anno (in the year of) or pinxit (painted by). Beware the word da (Italian for “after”); it usually means that the artist painted it in imitation of an existing painting.

Most of our grandmothers didn’t own “important” jewels. Grandma was far more likely to have owned modest jewelry — a locket, perhaps, or an enameled bracelet, maybe a string of pearls with a ruby clasp. But the jewelry she wore still probably reflected the aesthetics of the day.

You can determine your jewelry’s age by evaluating these key elements:

- Materials: Is the setting silver, gold or platinum (look for marks on the metal)? Is the centerpiece a precious stone (diamond, ruby, sapphire, emerald), semiprecious stone (amethyst, topaz, garnet, turquoise, opal, citrine, aquamarine, lapis lazuli, jade) or organic material (pearl, tortoiseshell, ivory, coral, amber, jet)? Are the stones real?

- Technique and style: During the 16th and 17th centuries, gems had closed-back settings, and in the 18th and 19th centuries, a piece of foil was added between the gem and the back to enrich the color of the stone. Gems began to be set in prongs during the 1800s. Art Deco’s dazzling, geometric designs surfaced in the 1920s, followed by “white” jewelry — diamonds and platinum — in the ’30s.

Be sure to thoroughly examine old jewelry for flaws that diminish its value. You can usually feel if a piece has been repaired, and the back should be as well-made as the front.

Clocks and Watches

Four criteria determine if a clock or watch has value. Mechanical complexity, the maker’s reputation and a fine aesthetic all contribute to a timepiece’s value, but first and foremost is condition. Ideal timepieces are not only in their original condition — they work, too. Extensive repair or missing original parts seriously diminish a clock or watch’s value. What should you look for in an old timepiece?

- Clocks: Tallcase (commonly called “grandfather”) clocks often have new movements (the gears and parts that make it tick). Check for gaps between the clock and dial. Condition is crucial for bracket, shelf and mantle clocks. Engraving or an original key can increase their value.

- Watches: About 95 percent of all pocket watches, railroad watches and wristwatches aren’t valuable. A watch is worth more if it has an elaborately painted, enameled, jeweled or gold case, or has jewels in the movement. Gold watches should be stamped with 14K, 18K or 750; marks of “Guaranteed for X years” and “GF” indicate gold-plating. Key-wound watches are usually older than stem-wound pieces.

Metalwork

Many antique metal objects can still be found today. But if we arrange the metals in descending order of value — bronze at the top, followed by brass, copper, pewter and iron — our “finds” will be bottom-heavy. Let’s look at the objects typical of each kind of metal:

- Bronze: It’s heavy and distinctly cold to the touch. Genuine bronze sculptures exhibit clear, sharp detail in every feature; always show finishing-file marks; and don’t rust. When bronze weathers, it acquires patinas of lustrous brown, brilliant blue or the familiar turquoise-green. White metal, or “spelter,” is an easy-to-recognize imitation. Spelter is never cold to the touch, doesn’t show file marks and corrodes with age. When scratched, spelter looks gray rather than bright gold.

- Brass: This metal was ideal for complicated shapes such as candlesticks, fireplace furnishings and warming pans (round boxes that held hot coals and could be slid between sheets to warm an icy bed). Brass is often coated in lacquer to keep it from tarnishing. One way to date brass candlesticks is to look at their underside; after 1890, they were left unfinished and appear roughened.

- Copper. By the 18th century, copper was made into practical objects such as kettles, pots, stills and dry and liquid measures.

- Pewter: Most pewter we find today is in the form of 16- to 20-inch plates. American examples can often be distinguished by a molded edge around the rim. Pre-19th century pewter is rare and is frequently marked.

- Iron: In the 18th and 19th centuries, blacksmiths fashioned wrought (hand-forged) iron into practical objects such as hinges, door hardware, axes and trivets. Ornamental wrought iron was expensive, custom-made work, and is correspondingly valuable today.

Rugs, Quilts and Samplers

Textiles are true folk art, combining beauty with utility, freshness, originality and the sweetly awkward touch of the human hand. And since cloth is fragile — wearing, shredding or fading with age — we’re lucky to have antique textiles at all.

- Rugs: Only handmade rugs are valuable. Look for dyes in genuinely old rugs to shade, often in the middle of a design. Called abrash, the color change results from inconsistencies in different batches of wool yarns and is not a flaw. Folk rugs include rag, hook, yarn-sewn and Shaker braided rugs; too-strong, too-fresh colors are signs of a modern folk rug. Native American rugs are highly collectible.

- Quilts: For women, quilts were a welcome creative outlet and justifiable source of pride. They’re also unique among antiques. With quilts, age is less important than beauty — the more brilliant the colors, the more elaborate the design, the more the quilt is worth. Machine stitching isn’t even a drawback. It’s simply a convenient tool for dating quilts: an indication that a piece must have been made after 1850 (when sewing machines became widely available). Amish, African-American and American flag quilts all command a premium. Knowing the maker’s name adds to a quilt’s value.

- Samplers: Thousands of samplers still exist to tell us about the times, values and independent views of the girls who made them. Alphabet samplers were the most common, but girls also stitched maps, animals, people, buildings and even genealogies — samplers that recorded births, deaths, marriage dates and quite literally family “trees.” The easiest tool for dating a sampler is the date, often stitched in. Unusual motifs and departure from the ordinary add to a sampler’s value, as does its presence in the original frame.

Toys, Dolls and Collectibles

Collectibles don’t have much intrinsic value, but they do have serious nostalgia value. In this realm, condition and rarity rule.

- Toys: Because the majority of toys were mass-produced, they can usually be dated by their maker’s marks, by marks denoting their country of origin and (after 1870) by their patent numbers. The US Patent Office will provide the maker and date of the patent application for a small fee. The most valuable toy is the toy that’s never been played with (even the packaging should be like new).

- Dolls: Dolls are classified by the material from which their heads are made — china, papier-mâachée, wood, bisque, cloth, plastic. Dating can often be tricky; check for clues such as marks and physical characteristics.

- Collectibles: The choicest collectible will still be in its original box — if there was a box — and as close to “untouched” as its years and function allow.

Books and Manuscripts

Here’s the category for Uncle Harold’s first-edition Huckleberry Finn and Great-aunt Petunia’s Civil War diary. A few tips on evaluating them:

- Books: “First edition” is the key word in collectible books. If no edition number is listed on the back of the title page, consult a reference book to learn which edition matches the publication date. Remember that the fewer there are, the more valuable a book becomes. And signed books (especially with rare signatures) command a premium. No matter how old the book, its condition will be compared with brand-new books today.

- Manuscripts: Letters, deeds, wills and speeches can illuminate history in surprisingly revealing ways. You can confirm age by papermaking technique. Doubt the validity of presidential signatures; for instance, “Lincoln-signed” land grants were so numerous because land agents were given authority to sign for the president.

Finding an Appraiser

Acquiring antiques expertise is a lifelong task — one that requires years of looking, listening and reading. So if you’re in possession of a potentially valuable object (and if Antiques Roadshow isn’t coming your way soon), you’ll want to know how to find a good appraiser, and, most particularly, an appraiser who’s knowledgeable about your category of objects.

To locate a qualified appraiser, call the appraisal department of an auction house (see the box at left) or contact the American Society of Appraisers, the Appraisers Association of America or the International Society of Appraisers. Such groups keep databases of members throughout the country and their specialties and are happy to refer you to someone in your area.

Of course, the value of antiques isn’t measured just in dollars and cents. Whether it’s a toy train you stumbled upon in Dad’s attic or a quilt that’s been passed down from Great-great-great-grandma, every family heirloom has a story to tell. The memories and history that surround it keep your family history alive — for you, and for the generations to follow. It could be worth $5,000 to a collector or only 50 cents, but as part of your heritage, it’s priceless.

- Artifacts and Heirlooms recording form and Heirloom Inventory form (free downloads)

- Best practices for handling keepsakes (free online article)

- Heirloom Preservation Made Easy on-demand webinar (available from Family Tree Shop)

ADVERTISEMENT