Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

You might say my third-great-grandfather Joel Stow epitomized the “American way.” After all, the story of this country’s settlement is largely the saga of the way west, as families in search of land and opportunity left the increasingly crowded Eastern Seaboard. These pioneers followed a tangled network of roads, canals and rivers into rough-and-tumble territories that became settled, civilized new states. Tragically, of course, America’s Manifest Destiny — as columnist John O’Sullivan termed the doctrine of predestined expansion across the continent — also led to the displacement of Indian tribes from sea to shining sea.

Joel’s and my other Stow ancestors’ part in this moving story took place mainly between Virginia and Alabama, with stops along the way. By studying common migration patterns, I was able to narrow their possible locations and focus my record searches. Tracing your own family’s paths back into American history can prove crucial to identifying previous generations and, eventually, figuring out where and how they arrived on US shores. Knowing the network of trails American pioneers traveled can help you guess where to start looking. These research tips and trail overviews will help you understand routes that brought Americans westward, so you can begin to trace your family back eastward — and back in time.

US Migration Chains

Starting about 1837, Joel Stow manned one small link in the US migration chain. He ran a ferry on Alabama’s Tallapoosa River, which settlers and traders crossed as they pushed ever deeper into the “Old South-west.” His customers may have come down the Fall Line Road, which followed a band of river rapids and linked the towns that grew up along them. The Fall Line Road took travelers from Virginia all the way to Augusta, Ga. From there, the Federal Road headed west through Columbus, Ga., and across Alabama to just south of the Tallapoosa, before angling toward Mobile.

Stow’s family (at least my part of it) didn’t migrate much farther, winding up in nearby Opelika, Ala. There, they intermarried with other Virginia families that took the Fall Line Road or other paths through the Carolinas and Georgia. Because that was such a common migration pattern — almost every branch of my mother’s family used some variation of it — I knew where to start searching for Joel Stow’s parents. The Stows’ last stop before Alabama was likely either Georgia or the Carolinas; a generation or two further into the past, I knew I’d be looking in Virginia.

North Carolina indeed turned out to be the answer, as I found using one of the best and simplest sources for tracing migrations: the US census. Beginning in 1850, it named all free individuals, not just heads of household, and added the state of birth. Sure enough, Joel Stow’s 1850 entry says North Carolina. For confirmation, though, I turned to the 1880 census — the first to also list birthplaces of people’s parents. The 1880 entry for Joel’s son, my great-great-grandfather John Ashley Stowe, shows his father as born in North Carolina. (John’s wife, according to family lore, added the e to make the surname look “fancier,”) Searching North Carolina marriage records, I’ve identified an Abraham Stow as the likely father of Joel. If I hadn’t been able to find answers in the census, I could’ve started searching for the Stow surname in Georgia — especially the places through which migrants might’ve passed en route to the Tallapoosa River. Next I would’ve hunted in the Carolinas, where indeed there are at least two branches of Stows.

Using Records to Find Migration Answers

Though certainly the easiest source for migration answers, the census isn’t the only place you’ll find clues to your ancestors’ paths. Check for birthplaces in cemeteries, church records, military records, family Bibles, probate files and newspaper obituaries. Remember, a family might have made an intermediate stop between their hometown and the place they settled for good. Many of my Southern kin, for example, were born in Virginia or North Carolina, lived in Georgia and died in Alabama. I’ve found valuable clues in their easily overlooked Georgia records.

Land records, which may list a buyer’s or seller’s last residence, can be useful even when the information isn’t so obvious. You can search databases of land records, such as the Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office patents, for your ancestors’ legal footprints where they may have left no other evidence. That database contains information on government land sales. Transactions between private citizens (deeds) would show up in county courthouses. Once you’ve found an ancestor’s land, take note of families with neighboring tracts. Even if their surnames aren’t familiar, they may be your relatives, too, since neighboring families often migrated together and intermarried. Likewise, if you get stumped tracing your family, try searching for the neighbors. If neighbors of your Ohio family all came from Lancaster, Pa., it’s worth checking to see if your ancestors made a stop there, too.

Study the roads and routes that often brought people to your family’s hometown. Follow them eastward to identify locales where your ancestors might’ve paused — for a few years or a few generations. Then check census and other records in those places. It may help to compare your family’s arrival date in each place with the timelines of possible routes they traveled and places they stopped. Consult histories of those places: Even if these books don’t mention your family by name, they can give clues to why and from where settlers in the area arrived.

Collections of old maps — many now posted on the Internet — can help you trace your ancestors’ route. The University of Alabama’s historical map collection <alabamamaps.ua.edu/historicalmaps>, for example, helped me pinpoint where the Federal Road and the Tallapoosa River most nearly intersected. Many state archives have map collections, and the University of Texas’ Perry-Castaneda Library has historical maps from across the country <www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical>.

Consider your ancestors’ possible motives for embarking on the often-perilous journey west, and match their movements to mass migrations at that point in history. Did the Gold Rush lure your family to California? Did they, like many of my forebears, catch “Alabama fever” in the first half of the 19th century, as former Indian lands were opened to settlement? Your ancestors might’ve had less pecuniary motivations for migrating, such as the Latter-day Saints who followed the Mormon Trail to Utah starting in 1846, or my great-great-grandfather the Rev. Robert R. Dickinson, a “circuit rider” Methodist minister in Alabama in 1840.

Migrations were involuntary for some, such as the 16,000 Cherokee who followed the Trail of Tears to Oklahoma in 1838, or the Nez Percé who fled the US Cavalry in 1877. Histories of displaced tribes will help you sort out their movements, as will Bureau of Indian Affairs records at the National Archives and Records Administration <archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/075.html> and Family Tree Magazine‘s April 2004 American Indian research guide.

The Most-Traveled Land Routes by Destination

Note that although knowing popular historic roads can solve many migration mysteries, not every pioneer used them. We’ve grouped the following most-traveled land routes geographically by destination, so you can start your research where your ancestors ended up.

Kentucky and Tennessee

Wilderness Road: It’s easy to forget America’s frontier once was Kentucky and Tennessee, the 15th and 16th states admitted in 1792 and 1796, respectively. Daniel Boone and George Rogers Clark blazed the path to the American interior. Boone led his own and five other families through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky in 1775, pathfinding what later became known as the Wilderness Road. Word of the bluegrass paradise Boone reportedly found over the Appalachians spread swiftly through a population eager for an alternative to high taxes, crowded coastal states and post-Revolution economic woes.

By the time Britain formally ceded the trans-Appalachian west to the new United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, thousands had already made Kentucky their home. During the 17 years between Boone’s trailblazing and Kentucky’s statehood, some 70,000 settlers surged through the Cumberland Gap. By the 1800 census, the Bluegrass State’s population had exceeded 220,000.

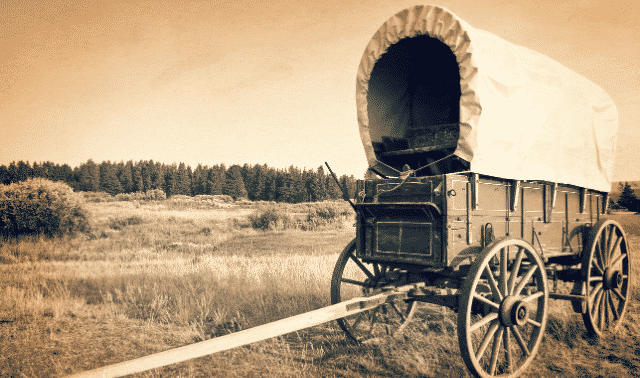

At Bristol, Va. (then called Sapling Grove), the Great Valley Road gave way to what was originally called Boone’s Trace through the Cumberland Gap. The route became known as the Wilderness Road after 1796, when it was widened to accommodate Conestoga wagons.

Some Kentuckians-to-be followed Zane’s Trace to Maysville, Ky., on the Ohio River. Tennessee-bound settlers took the Knoxville Road south from Kentucky to the Nashville Road, or took the Nickajack Trail from Fort Loudon (now in Tennessee) to the Chickasaw Trail (later renamed Robert’s Road).

Richmond Road: Many settlers bound for Kentucky traveled this route through Virginia from Richmond to Fort Chiswell, where it joined the Great Valley Road. Others followed the Great Valley Road from Maryland or Pennsylvania.

Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia

King’s Highway: Incorporating the Boston Post Road that first carried mail between Boston and New York in 1673, the King’s Highway could be considered America’s first interstate highway. It eventually stretched 1,300 miles south from Boston through most of the Colonies’ important cities, to Charleston, SC, a journey of two months or longer.

? Great Valley Road: Known to Indians as the Great Warrior Path, the forerunner of this trail reached all the way from New York to present-day Salisbury, NC, where it connected with the Great Trading Path. Its feeders included the Philadelphia Wagon Road, which in the 1740s, linked up with the Pioneer’s Road from Alexandria, Va., and went on to the Scots-Irish settlement of Winchester, Va. Pioneers from this route began streaming into the Shenandoah Valley. Among those following the Great Valley Road into the Shenandoah and on to the Piedmont region of western North Carolina were Scots-Irish, Quakers and Mennonites. The Great Valley Road also became an important feeder into the Wilderness Road.

Fall Line Road: The route my ancestors used followed river towns through the heart of the Carolinas. Beginning about 1735, travelers would leave the King’s Highway at Fredericksburg, Va., and head southwest to Augusta, Ga., founded in 1736 at the head of the Savannah River. Other towns near the route include Cheraw, SC (founded about 1750); Camden, SC (started by Quakers as Pine Tree Hill in 1751); and Raleigh, NC (established in 1792). Eventually, many Alabama- and Mississippi-bound pioneers would follow the Fall Line Road to join the new Federal Road in Columbus, Ga.

Carolina Road: An alternative to the Fall Line Road, the Carolina Road (also known as the Upper Road) tracked farther to the west, through Hillsboro and Charlotte, NC, in the 1750s. It originally extended only to Greenville, SC, but in 1828 connected to the Federal Road at Athens, Ga.

Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas

Federal Road: Historians Henry deLeon Sutherland Jr. and Jerry Elijah Brown write, “The chances are good that all who trace their ancestry to anywhere in Alabama south of the Tennessee Valley have a forebear who came over the Federal Road.” The route was born in 1806, when Congress appropriated $6,400 for a road to carry the mail between Athens, Ga., and New Orleans. It was widened and partly rerouted in 1811 to better accommodate military needs for the looming war with Great Britain; construction went west to east, connecting Fort Stoddert, Ala. (north of Mobile), to Fort Wilkinson, Ga., on the Chattahoochee River, where the route merged with the original postal path. Combined with the defeat of the Creek Indians in 1814, the Federal Road sparked the greatest mass migration in the nation’s history up to that point. By 1820, more than 200,000 people had taken up residence in Alabama and Mississippi.

Natchez Trace: The first major north-south route in the Southern states, the Natchez Trace followed Indian trails from Nashville, Tenn., to Natchez, Miss. (on the Mississippi River). After negotiations with the Chicasaw and Choctaw tribes for safe passage through their lands, US troops began building north from Natchez and south from Nashville, joining in 1803. The 500-mile route was upgraded in 1806, and briefly supplanted by the Jackson Military Road, which reached New Orleans in 1820.

Enterprising barge and keelboat pilots would sail down the Mississippi, unload their cargo and sell their boats, then return on the Natchez Trace, where they often met other frequent travelers — bands of thieves. Besides the threat of robbers, settlers traveling the trace had to brave clouds of mosquitoes and horseflies. No wonder the trace was nicknamed “the Devil’s Backbone.”

New York and Pennsylvania

Mohawk Trail: Pioneers in New York began to migrate west along the Mohawk River Valley as early as 1725, and by 1770, the Mohawk Trail reached from Albany to Buffalo. After the Revolutionary War, the overlapping Catskill Turnpike brought more settlers west. Finally, in 1825, the Erie Canal provided a 350-mile waterway from Albany to Lake Erie.

Braddock’s Road: British Gen. Edward Braddock built this route — the first to cross the Appalachians — connecting Cumberland, Md., on the Potomac River to the Monongahela River south of present-day Pittsburgh. In 1813, construction began on the Cumberland Road (later, the National Road), which followed much the same northwesterly route.

Pennsylvania Road: Incorporating the Great Conestoga Road and the later Lancaster Pike, the Pennsylvania Road stretched from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh at the head of the Ohio River. Much of the route from Harrisburg west followed the early path of Forbes Road, blazed during the French and Indian War.

Northwest Territory

Zane’s Trace: In 1796 and 1797, when Ohio Territory first opened to legal settlement, Col. Ebenezer Zane built this road (also a route to Kentucky) through Ohio between Wheeling, WV, and Maysville, Ky. The segment between Wheeling and Zanesville, Ohio, also called the Wheeling Road, was ultimately upgraded and incorporated into the National Road.

National Road: Soon after Ohio was carved out of the Northwest Territory and admitted to the Union, Congress passed legislation in 1806 to build the first federally funded interstate highway to transport eager settlers there and beyond. Originally called the Cumberland Road, the route came to be known as the National Road by 1825 because of its funding. Construction of the 600-mile span, which eventually stretched from Cumberland, Md., (incorporating the old Braddock’s Road) to Vandalia, Ill., began in 1811. The westernmost 89-mile section connecting Indiana to Vandalia, then the capital of Illinois, opened in 1839, though the final stretch through Indiana had to wait until 1850.

In a history of the road, P.D. Jordan wrote of the streams of migrants: “Covered wagons had been forming an endless procession ever since the Cumberland Road was opened. After they settled Pennsylvania, they filled Ohio. When Ohio land was no longer available, they clumped on into Indiana to erect their homes and plant their fields on the banks of the Wabash. They clung to the National Road like a mosquito to a denizen of the swampy American Bottoms. It was the people’s highway, and the people crowded it from rim to edge until their carts, wagons, stages and carriages challenged one another for the right of way.” Today, US Route 40 follows the National Road.

Chicago Road: An 1821 Indian treaty gave the US government the right to build a road between Detroit and Chicago. The crude and curvy road, built between 1829 and 1836, brought pioneers west by the thousands to settle southern Michigan and Illinois. Today, the Chicago Road survives as US Route 12 and the famed Michigan Avenue.

State Road: Connecting to the Chicago Road, the State Road extended west from Chicago through Elgin and Rockford to Galena, Ill., on the Mississippi River. After the discovery of lead in the 1820s, Galena (from the Latin word for lead sulfide) became a boomtown while Chicago was still a village.

The Southwest

Old Spanish Trail: Following a rough network of Indian footpaths, the Old Spanish Trail became the route — rather, routes, as several variants developed — between Santa Fe and Los Angeles. The 2,700-mile trail crossed deserts, canyons and Death Valley to connect these key outposts of what was then Mexico, from 1829 to 1848.

El Camino Real de los Tejas: During the Spanish colonial period, this was the primary overland trail from what’s now Mexico, across the Rio Grande to east Texas and the Red River Valley in what’s now northwest Louisiana. San Antonio, Nacogdoches and Laredo were founded along this ever-changing, 2,500-mile route.

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro: This north-south route connected Mexico City with what’s now northern New Mexico. Recently named the newest national historic trail, its US section stretches from El Paso, Texas, to San Juan Pueblo, NM.

Santa Fe Trail: More a commercial route than a migration path, this famous trail also was traveled by gold seekers and by American troops who seized Santa Fe in the war with Mexico. The 1,200-mile route through five states, from Franklin, Mo., to Santa Fe, NM, served travelers from 1821 until the railroad arrived in 1880.

Utah, California, Oregon and Washington

Mormon Trail: After a mob killed Mormon founder Joseph Smith in 1844, new leader Brigham Young began planning to move his 11,000-some followers from Nauvoo, Ill. After reading John C. Frémont’s report on the West published that same year, the Mormons chose the Great Salt Lake region as their destination and set out in 1846. The Mormon Trail crossed Iowa and the Missouri River to the site of present-day Florence, Neb., where the travelers set up winter quarters. Then they followed the north bank of the Platte River from Fort Kearny, Neb., to Fort Laramie, Wyo., where they turned southwest to Salt Lake City. By 1869, some 70,000 Mormon faithful had made the trek to their “new Zion” in Utah.

Oregon Trail: Originally blazed — in reverse — by fur trader Robert Stewart in 1810, this harrowing route from Missouri to Oregon first carried wagons in 1836. Though Marcus and Narcissa Whitman’s missionary party had to abandon their wagons 200 miles shy of their destination in the Walla Walla Valley, they showed the way for thousands who would follow to Oregon and later Washington. The mass migration began with a wagon train of more than 100 pioneers who left Elm Grove, Mo., in 1842.

The Oregon Trail covered 2,000 miles across seven states, and some 34,000 travelers in all perished en route — 17 deaths per mile. It stretched from Independence, Mo., to Fort Kearny, where the route then paralleled the Mormon Trail along the Platte River (except on the south bank) and across Wyoming to Fort Bridger. There the Oregon Trail turned northwest through what’s now Idaho. At The Dalles, Ore., migrants had to choose between the treacherous Columbia River or, after 1846, the safer but longer Barlow toll road across the Cascade mountains to the Willamette Valley. By the 1850 census, Oregon numbered 12,093 people; a decade later, the new state boasted 52,495 inhabitants.

California Trail: A small band of 58 Oregon Trail trekkers split up at Soda Springs, Idaho, after passing Fort Bridger, in 1841. Half went to Oregon while the rest blazed the California Trail. They followed the Bear River, crossed the Great Salt Lake Desert and braved the Sierra Nevada Mountains. In the years to come, more than 300,000 people would follow in their footsteps to destinations in California and Oregon. Not all survived the trip, including 40 of the infamous 87-member Donner Party. In 1846, after taking the ill-advised Hastings Cutoff — a supposed shortcut — the party reached the Sierra Nevadas late in the year and got trapped all winter.

Migrants catching “gold fever” from the 1848 discovery of gold at California’s Sutter’s Mill tried various other routes and cutoffs. Some headed north of the Great Salt Lake, through a corner of Idaho, rejoining the trail at the Humboldt River. From Nevada, the Lassen Route aimed north of Sutter’s Mill, while the southerly Carson Route headed southwest.

De Anza Trail: In 1776, long before California’s gold rush, Spanish Lt. Col. Juan Bautista de Anza led almost 300 people over 1,200 miles to settle Alta (Upper) California. The first overland route connecting New Spain with San Francisco, the US segment begins at Nogales, Ariz.

For detailed information on these routes and less-frequently used byways, consult the resources in the toolkit on the opposite page and see Beverly Whitaker’s Early American Roads and Trails Web site <freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~gentutor/trarls.html> (especially her downloadable PDF guides to 18 trails). However your ancestors arrived at wherever you’ve found them in records, retracing their routes can lead you to new discoveries about your family and their journey through history.

A version of this article appeared in the March 2008 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT