Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

So your ancestors appear to have disappeared. From the census, where they’d been consistently listed for decades. From the J section of the city directory. From tax lists that recorded your family’s payments for years.

You may eventually find your kin somewhere else and piece together an explanation behind their move. On the other hand, your family might still be exactly where you last saw them, but something else changed: the city or county boundary, the street name or their address. To figure out which scenario applies to your situation, ask yourself four questions about the place where your family lived and the neighbors who resided nearby. Once you determine whether it’s your family or their address that was the moving target, you’ll be able to track down that census, city directory, tax or other record you need.

1. Are you looking in the right state and county?

Let’s say you find a relative listed in Brooke County, Va., in the 1840 census. You look for an address for the Brooke County courthouse to order her marriage record, only to find that no such county exists in Virginia. That’s because Brooke County was among those that seceded from Virginia in 1862 to form West Virginia.

Boundary changes have occurred with surprising frequency in counties, colonies and states. In 1712, for example, Carolina split into North and South Carolina. About 20 years later, Georgia was carved from South Carolina. If you lived in northern Massachusetts in 1820, you would’ve woken up one morning to find you lived in the brand-new state of Maine. Several states have disputed their common borders, including Ohio and Michigan, and Iowa and Missouri.

As territories evolved and young states grew, their county boundaries changed and multiplied. Ohio had nine counties when it became a state in 1803; today it has nearly 10 times that number. California has more than doubled its original 27 counties, revising most of its boundaries since achieving statehood. County boundary changes persisted well into the 20th century in many states. To a lesser extent, they still happen today: Broomfield County, Colo., was created in 2001.

You have several options for learning the boundary history of a particular place, from researching the original legislation that established counties to reading state or county history books. But the easiest way is to consult a boundary reference tool online. The Newberry Library’s

Atlas of Historical County Boundaries compiles all boundary changes chronologically and geographically.

Unfortunately, its handy interactive map has been disabled for some time; a new version is being tested. A newer online tool called

Historical US County Boundary Maps utilizes that atlas’ data and lets you look up the boundaries of a certain place as of an exact date, overlaid on a present-day Google map.

To use it, type a present-day address (or even just a town and state) and a date or year into the boxes. Hit Go. You’ll get an interactive, present-day Google Map overlaid with county boundaries as of the historical date you’ve specified.

Above the map, the county name as of your specified date is shown, along with the most recent law or change that led to the boundaries you’re viewing. If you want to see a full timeline of all the counties (and states) your spot on the map has ever been a part of, just check the box beneath the map labeled Show Complete County Change Chronology.

2. Are you looking in the right locales?

US cities and towns have changed boundaries even more than counties and states, as they annexed land, separated themselves from surrounding counties and renamed themselves. But you’ll research those changes a little differently. For one thing, there are so many more locales. Today’s maps show nearly 20,000 incorporated places in the United States, and that doesn’t include now-abandoned places. Furthermore, a single state may have several places with the same or similar names—a city, county and multiple townships all called Hamilton, for example. And once you’ve identified the right town, there’s no single online tool that maps all municipal boundary changes.

Look first for place clues in genealogical documents. Confirm the name and type of locale (such as a town, city, village, township or military district). Note whether the county is mentioned, as well as any nearby towns that may help you find it on a map. US census listings typically have the city, county and state written across the top of each page. Digitized city directories may include this information in the front pages.

Obituaries, military enlistments, probate records and other records may mention a locality’s name but not fully describe where it is. Look it up in the

Geographic Names Information System, a master database of present-day and obsolete places, including landmarks such as knobs, arroyos and mines. You may discover several options for a locale within a single state. Take it a step further by consulting US Geological Survey (USGS) topographic maps back to 1879 at the

USGS National Geologic Map Database. Here, you can visually explore both man-made and natural landmarks on downloadable high-resolution maps.

If you’ve found an ancestor’s property, use deed or patent descriptions to identify the town’s original name and gather other location clues. A few municipalities and counties have online databases of deeds and property descriptions, but most don’t (or they may include only recent transactions). You may be able to research deeds in microfilmed indexes and deed books. To find these, run a place search of the FamilySearch online catalog and look under the Land and Property heading. Click to borrow the film for a fee through your local FamilySearch Center (if you’re lucky, the catalog will link you to digitized records on the FamilySearch site). If you don’t find microfilm for your ancestor’s town or county, check with the local historical society. You may need to research deeds in person or hire a local researcher. See our deeds research guide for more.

If your ancestor acquired land from the federal government, search the millions of digitized land patents at the

General Land Office Records website. Properties are described by county and by township, range, aliquots (a legal land description) and section (a mapping system used to survey public lands). In many patent entries, you can click a box to see the description on a modern map. Look at the patent image to see whether the owner was a resident of another place at the time of purchase.

Once you’ve identified a town, research its boundaries at a given time to make sure you’re looking for your family in the right local records. This is especially important in New England, where many genealogical records are kept on the town level. Outside New England, you still may find local records of value: birth and death records that predate statewide vital recordkeeping, tax and voters’ lists, city directories, neighborhood-level maps and more.

Pay special attention to the boundaries of towns that are now part of a major metropolis. As cities have grown into each other over time, they may have merged, been annexed into one another or experienced significant land loss or gain. For example, the former cities of Auraria and Highlands are now part of Denver, Colo. New Orleans only had seven wards in 1805; by 1874, it had 17. If the city has a shoreline, look closely at that, too. You may find evidence of receding or filled-in shorelines that would’ve impacted your ancestor’s property.

3. Did the street name or address change?

By now, it’s clear that you can trust very little to remain unchanged on old maps. Street names and house numbers in cities are no exception. Many cities standardized their street naming and numbering practices in the late 1800s or early 1900s, renumbering houses to fit the grid. Neighborhoods that were annexed to a nearby city sometimes changed their names and numbers. Main thoroughfares are renamed—to this day—in honor of local heroes or to accommodate popular tastes. Development can reroute roads or break them up into sections and lead to renaming. Streets and even entire neighborhoods might be cleared for highways and other projects.

If you’re trying to trace an address backward in time through name changes, try these steps:

- Find the property description in the deed recording the property transfer. Look for the lot and block number and subdivision name. Older deeds very often didn’t list street addresses.

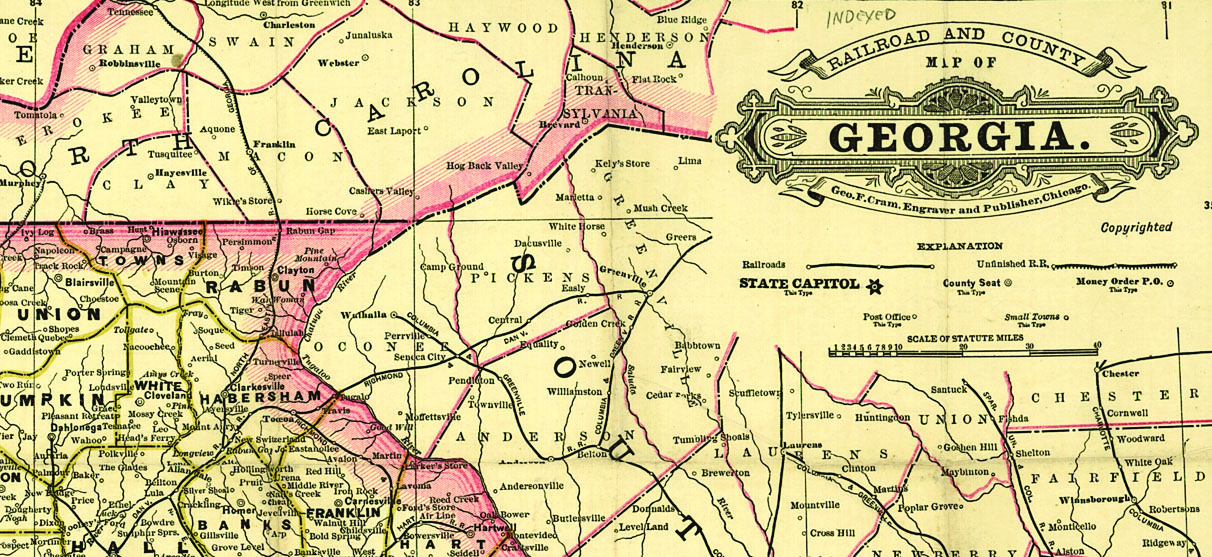

- Look for old plat maps created by the local or county assessor showing property ownership, lot boundaries, block names and neighborhood developments. Ask for these at town or government offices, local historical and genealogical societies and libraries. Search online in your favorite web browser with the city, state and the phrase plat map. Browse major online map collections such as David Rumsey Map Collection and the Perry Castañeda Library Map Collection.

- Check Sanborn fire insurance maps or historical atlases such as Baist’s real estate atlases (search for Baist real estate atlas and a city name) to see building structures and possibly street addresses.

- Look for a guide to local street name changes in the local history or genealogy section of your local library, or an online database such as that hosted by the New Orleans Public Library. Local genealogical society websites often have information on changes, and you may find them detailed in city directories published that year.

Once you have an address, search US census records by street name and house number, following the step-by-step instructions in the box on the previous page. This can help you find elusive ancestors in the census; see whether other relatives lived there previously or subsequently and learn more about the history of the home.

4. Can the neighbors help?

If you can’t find your family’s home in a given census or city directory, their neighbors may be able to point you in the right direction. First, note the names of your family’s neighbors in previous or later censuses and city directories. For the latter, keyword-search for the address in digitized directories or consult the criss-cross listings (if the directory has them), which are arranged by address. Then search for the folks next door and see if your family is near them. You may find that your relative’s name was written or indexed differently than you’d expect. You may also learn that someone else lived in their home at the time, or that the home doesn’t appear to exist.

Our case study demonstrates how you might compare the neighbors in two different record sets—in this case, a map and a US census listing—to confirm they refer to the same set of people. Several men named “J. Felix” lived in Somerset County, Pa., at the same time. The number of neighbors names appearing in both the 1876 map and the 1880 census helps confirm that the J.A. Felix on the map is the same as the John A. Felix in the census.

These strategies and principles all come together in the example. In that instance, maps pointed the way to street and address changes, with neighbors’ names providing the final clues. That complicated research path eventually led to the home’s front door—right where it was supposed to be.

More Online

From the May/June 2017 Family Tree Magazine