Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

When you hear the word “Italian,” what does it bring to mind? I think of my grandmother and Sunday afternoon dinners with her fabulous spaghetti sauce. October is Italian-American heritage month, and there’s no better way to celebrate your heritage than to gather around the Italian dinner table and begin recording information about your Italian family history. Italian-Americans, like other ethnic groups, risk losing their unique customs and traditions as they’re assimilated into “American” culture. One way of keeping that ethnic culture alive is to trace your family history and study the lives of your Italian ancestors.

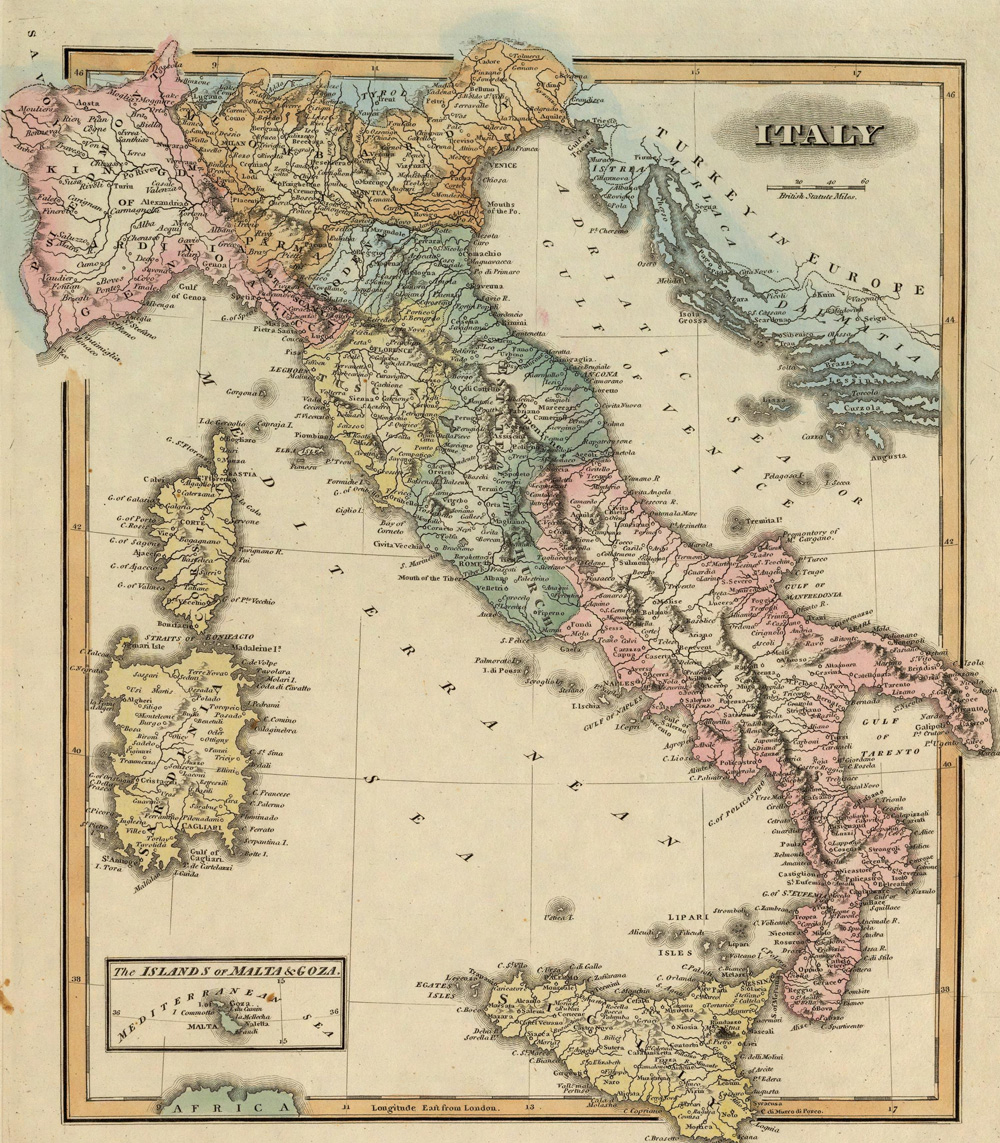

Northern Italians began arriving in America in small numbers during colonial times. Because Italy wasn’t unified until the 1860s, its people considered themselves citizens of a village or region, rather than a nation. In the records you may find these early arrivals recorded by region — Genoese or Florentine, for example — rather than as “Italian.” Those who arrived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were mostly Italian peasants and unskilled laborers from southern Italy — the regions of Abruzzi, Molise, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria and Campania, parts of Latium, and the island of Sicily.

One of the most common mistakes researchers make when tracking their Italian origins is anxiously jumping the ocean too soon. No one wants to trace the wrong ancestors, which is entirely possible if you don’t thoroughly research each generation in America. Follow these 10 steps to keep from “drowning” in the ocean and to make your Italian research more successful and fulfilling.

Step 1: Begin with home sources

To start your search, you need to know certain information — names, dates and places — and sitting around the dinner table after a nice Italian meal with a glass of vino and some relatives is a good opportunity to get this information. (I’ve yet to meet an Italian family that doesn’t love to talk about relatives who aren’t present. You may get some of your best stories this way.) All research begins with the who, where and when. In order to successfully research your Italian immigrants and continue the search in Italian records, you need to learn your ancestors’ full original names and the dates and places of their births. This information is usually obtained from oral family history or by scavenging through your home or relatives’ homes (with their permission, of course) for documents such as passports, citizenship papers, alien registration cards and birth, marriage or death certificates.

Record all the statistical information you find on pedigree charts and family group sheets, noting where each piece of information came from. Record the family stories in a notebook for now.

Step 2: Learn about genealogy in general

Next, read a basic how-to book on genealogical research methods and sources, such as Emily Croom’s Unpuzzling Your Past: A Basic Guide to Genealogy, 3rd edition (Betterway Books), Desmond Walls Allen’s First Steps in Genealogy (Betterway Books) or Christine Rose and Kay Ingalls’ The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Genealogy (Alpha Books). Everyone has the same starting point, whether your ancestry is Italian, German or Irish, whether your ancestors arrived in 1600 or 1900. Once you’ve looked at all the basic genealogical records, such as vital record certificates, censuses and so on, you’re ready to look for a naturalization record and passenger arrival list.

Step 3: Find naturalization records and passenger lists

From family stories, you may already know when your ancestors came to America and even the name of the ship — or you may have no clue. Look for naturalization records first, since those may tell you the date of arrival and the name of the ship, depending on when your ancestors came. To learn how to access naturalization records, see my new book, A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Immigrant and Ethnic Ancestors (Betterway Books) or Loretto Dennis Szucs’ They Became Americans: Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins (Ancestry).

Next, look for the passenger arrival list. Sources to help you find and use these records include my book listed above and John Philip Colletta’s They Came in Ships (Ancestry). If your Italian ancestors arrived between 1880 and 1899, an unindexed time period for many passenger lists, then look for the multi-volume series Italians to America: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. Ports, 1880-1899, by Ira A. Glazier and P. William Filby (Scholarly Resources), also on CD-ROM.

In the near future, there will be a massive database of New York passenger arrivals available at Ellis Island (see Family Tree Magazine, January 2000). This database is also supposed to be accessible through the Family History Library in Salt Lake City and its worldwide Family History Centers.

Step 4: Learn about Italian records

Once you’ve uncovered all American records for your Italian ancestors, it’s time to start learning about researching in Italian records. There are several books to help you:

• A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Italian Ancestors by Lynn Nelson (Betterway Books). This guide shows you how to research your Italian ancestors using the microfilms of the Family History Library.

• Finding Italian Roots: The Complete Guide for Americans by John Philip Colletta (Genealogical Publishing Co.). Colletta’s guide takes you into records in America and Italy.

• Italian-American Family History: A Guide to Researching and Writing About Your Heritage by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack (Genealogical Publishing Co.). My book focuses on researching Italians in America and how learning the folkways and customs of Italians can help your research.

• Italian Genealogical Records: How to Use Italian Civil, Ecclesiastical, and Other Records in Family History Research by Trafford R. Cole (Ancestry). An in-depth look at the records available in Italy and how to access them in person and from abroad.

Step 5: Study how your ancestors lived

While you’re learning about records in Italy, start learning about your ancestors’ lives. Keep in mind that you aren’t just looking for names, dates and places. Go beyond the skeletal pedigree chart and family group sheet — the who, where and when — and seek the person behind the name — the why, how and what was it like? Why did your ancestors come to America? How did they manage once they got here? What was it like to be a stranger in a strange land? Genealogical records don’t ordinarily tell us these answers.

You’ll want to explore the broader, common experiences and trends, the day-to-day activities and the folkways of Italian-Americans, such as:

Food — Anyone know an Italian who doesn’t like to eat? Whenever possible, Italian immigrants prepared and ate food they were used to eating in Italy. Those growing up in Italian households probably remember that food was a crucial part of family celebrations and daily life. Food represented the family, being a product of the father who earned the money to buy food and the mother who prepared it.

So how will learning about your family’s food habits help your genealogical research, besides adding some new recipes to your collection and a few inches to your waistline? Italian food is regional and may lead you to the area in Italy where your family came from, if you don’t already know this information. Or it may explain why your family ate certain foods and avoided others. When I interviewed my grandmother’s cousin about the family’s food habits, I learned they always had pasta at dinner meals, they only ate meat once a week — usually chicken, but they had a preference for eel — and pizza to them meant left-over bread dough topped with olive oil, onions and some tomatoes (no cheese). When I read about food preferences in Waverley Root’s The Food of Italy (Vintage Books) for the region of Apulia where my family originally came from, I learned this is precisely how my ancestors had eaten while still in the Old Country.

“Birds of passage” — By reading social histories of Italian-Americans, you may discover the reason your ancestor appeared on several passenger arrival lists. Many Italian men were “birds of passage” — immigrants who went back and forth between America and Italy several times before bringing their families over. This was the case with my great-grandfather, Albino DeBartolo, and it was puzzling to me at first. He originally came to America in 1905, went back to Italy a year or so later, came back to America in 1909, went back to Italy a year or so later, and finally returned to America for good in 1912. His wife and four children arrived the following year. Social histories gave me the probable reason for his behavior.

Southern Italians in general had a high rate of return migration — 30 percent went back to Italy within five years of arrival in America — so always check for your male ancestors in more than one passenger arrival list. The goal for many Italian men was to earn enough money in the United States to be able to return to Italy and buy land. Some men traveled back and forth to Italy several times before deciding to settle in America and bringing their families over. And since settling in America was not their original goal, birds of passage were also less likely to become naturalized citizens until after they’d lived in America for a number of years. My great-grandfather was a bird of passage who never became a US citizen, despite more than 35 years in America.

Naming patterns — The traditional naming pattern for southern Italians is to name the first son after the father’s father; the second son after the mother’s father; the third son after the father; the first daughter after the father’s mother; the second daughter after the mother’s mother; and the third daughter after the mother. If you don’t know the names of your immigrant ancestors’ parents, you can make an educated guess about their forenames based on this pattern.

For example, Salvatore and Angelina (Vallarelli) Ebetino named their children as follows:

1. Frances

2. Fortunato

3. Fortunato

4. Stella

5. Isabella

6. Felice

7. Michele

8. Michele

9. Salvatore

From this, we can reasonably guess that Salvatore’s parents’ names were Francesco and Stella, because of the names of the first son and daughter, and that Angelina’s parents were Fortunato and Isabella, because of the names of the second-born son and daughter. Further research confirmed this was exactly the case. Notice, also, that they named two children Fortunato and two Michele. This is because the first Fortunato and the first Michele died in infancy, and the names were used again (known as a “necronym”) for the next child born of the same sex to preserve the naming pattern.

These are just a few of the many Italian customs you may want to explore. Studying the social history will help you to better understand what you find in the genealogical records, help explain your ancestors’ behaviors, and give you great background material when you’re ready for step 10.

Step 6: Check neighbors and relatives

Make sure you’ve done all of your homework in America. By skipping generations here and becoming too anxious to start research in Italy, you increase your chances of tracing the wrong ancestors. If you haven’t found the name of your ancestors’ home village by the time you’ve completed steps 1-5, then your next step should to be to research your ancestors’ neighbors and relatives in America. Obtain the same types of records for these people as you did for your ancestors.

Italians tended to settle with friends and relatives from their homeland — think of all the “Little Italys” in major cities such as New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco and St. Louis. In fact, the people from a particular Italian region, city or village tended to settle in specific regions, cities or even certain city blocks once in America. In the 1890s in New York City, the area between Houston and Spring streets was occupied by Sicilians, while Italians from Genoa settled on Baxter Street.

Though Italy was unified by the time mass numbers of southern Italians began emigrating, these people still considered themselves primarily citizens of a town and were very regional. Language dialects varied from village to village and were incomprehensible to the residents of other regions; thus, Italian newcomers clustered in America with people who spoke their dialect. So discovering where neighbors and relatives came from may help you learn where your ancestors came from.

Step 7: Learn about your ancestors’ village

Of course, visiting your ancestors’ home village can’t be surpassed, but if you can’t make a trip to Italy, you can still learn something about the village from America. Depending on the community’s size, you may be able to find information about a village in travel guide books or on the Internet. Another good place to learn about a province or region is through Italian cookbooks: Look for ones that focus on a particular region of Italy, such as Flavors of Puglia by Nancy Harmon Jenkins (Broadway Books). Besides giving you recipes, these books often offer some historical and cultural background of the area.

Step 8: Bridge the ocean

Now you’re ready to bridge the ocean. You can do that several ways, most of which don’t require a plane trip. Work your way across the Atlantic in this order:

View Italian microfilmed records from the Family History Library. Through the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, you can access many types of records from throughout the United States and Italy. The library has more than 28,000 rolls of microfilmed original documents from Italy alone. I traced my Italian ancestors back to the late 1700s just from these microfilmed records, without ever leaving America’s shores.

If you can’t go to Salt Lake City, you can rent films for a small fee from one of the worldwide Family History Centers. To find a center near you and to see what records are available for Italy, search the Family History Library Catalog. Keep in mind, however, that while the Family History Library has an extensive collection, it doesn’t have every record for every time period or locality. Microfilming in Italy is still ongoing, so keep checking even though you might not find records for your ancestor’s village just yet.

The records will be in Italian, of course, but armed with a good Italian-English dictionary, you shouldn’t have any problem. Cole’s Italian Genealogical Records and Nelson’s A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Italian Ancestors show examples of the civil vital records and give translations.

Write to Italy to obtain records. The books listed in step 4 (except mine) will tell you how to write to Italian record repositories and even give you form letters translated into Italian that you can adapt to your family’s specifics. The Italian postal system has a reputation for being the worst in the world, however, so if you don’t get a response in about eight weeks, you might try sending your request again.

Hire someone in Italy to do research for you. Another new Web site can help you find a researcher in Italy: My Italian Family <www.myitalianfamily.com> provides research services for anyone who wants to explore the genealogy of their Italian families through a network of Italian and American researchers. But always be cautious of the researcher you hire — whether here or in Italy. Ask for the researcher’s credentials and when you might expect a report. It’s always better to get a referral from someone, rather than hire someone unfamiliar to you. By networking with other genealogists here in America who are interested in Italian ancestry, you can learn who you should hire in Italy.

A statue in Verona and a vineyard illustrate more than Italy’s romantic image — they also show the social and cultural context your ancestors lived in.

Make a trip to Italy to do the research yourself. While you may think this is obviously the best way to get records on your Italian ancestors, it may not be. Birth, marriage and death records are usually kept at the village’s civil registration office, and although one village may let you look through the ancient records until you’re blue in the face, another may restrict access. For example, when I was in Terlizzi, Italy, population of about 2,500, I was given carte blanche to the civil vital records. In Potenza, just 15 miles away and with a population of about 100,000, the clerk wouldn’t even let me breathe on the record books. If you’re in a situation where you can’t look at the documents yourself, have specific goals in mind and a list of names and dates, so the clerk can easily look things up for you, assuming that person is willing to do so. Remember, it’s especially hard to sweet-talk the clerk into looking up records, or possibly allowing you to look at the records, if you don’t speak the language.

Step 9: Find relatives in Italy

Not all of your ancestors’ relatives came to America. No doubt you have distant cousins still in the native village. Of course, one way to locate relatives in Italy is through the Internet, but remember that older family members in remote villages in Italy probably don’t even have computers. The good old-fashioned telephone directory and a letter may be your best bet. You can access Italian telephone directories on the Web at <www.teldir.com/eng/it>.

Step 10: Write your Italian ancestors’ stories

In this day and age when Italian families are often split by distance and there may be a loss of cultural heritage, it becomes all the more important to record your family’s history. But don’t just leave a collection of charts with names and dates. Write the stories of your Italian ancestors. If you combine family information with genealogical data and social history, future generations can gain an appreciation for what it took for their ancestors to leave their home in Italy and settle in America.

And don’t forget to preserve those gossipy family stories and food memories, too. For example, after one sumptuous dinner at Grandma’s house, where the family “oohed” and “aahed” over her spaghetti sauce, we all insisted we wouldn’t leave until we had her recipe. She shrugged her shoulders and said, “What recipe? You just open a jar of Ragu. Why spend all day making sauce when you can just buy it already made?” Of course, we were crushed, but today when I serve spaghetti made with Ragu, I proudly boast that it’s my Italian grandmother’s recipe. Tradition has to start somewhere, doesn’t it?

A version of this article appeared in the October 2000 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT