Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

You want something more. The names and dates, the bare-bones facts, the begats of genealogical charting just aren’t enough. You find yourself wondering what it was really like for your ancestors: how it felt to fight the war, expand the frontier, or overcome the prejudices. Welcome to the intersection of family history and “social history.” The study of ordinary people’s everyday lives, social history is history from the bottom up instead of the top down. Instead of focusing exclusively on the elite and famous, social history includes regular folks, women, ethnic minorities, people of varying age groups — in short, your ancestors.

women at work

Eighteen million women went to work outside their homes during World War II, many for the first time, to support defense industries and services. Find out how your female relatives fit into this important piece of social history.

In order to understand whole societies, social historians develop statistics from the same types of records that genealogists use when they research individual families, such as censuses, town and church records, or wills and deeds. But the historians usually are thinking about society collectively and watching for group patterns, rather than researching individuals.

Social history can put meat on the bones of your pedigree charts and family group sheets, adding historical context around whatever information you have on your ancestors. After all, your ancestors were not just individuals. They acted as part of groups, communities, neighborhoods and mass movements, even if they didn’t realize it. They migrated in chains. They settled in enclaves. They married and bore children in patterns. They voted in blocs. They responded to events in the same ways that their relatives and neighbors did or, when they deviated, those relatives and neighbors let them know what they thought about that!

Adding social history to your family history can fill in the missing pieces of your past to help you write about it in narrative form. It can help you understand your ancestors’ decisions and solve mysteries.

START WITH YOURSELF

Just as you do in genealogical research, begin your social history study with what you know about yourself, then your parents. Can you recognize yourself as part of groups such as clubs, classes, ethnicities or generations? Here’s a sample about my parents and me:

I was a late baby boomer, born in 1955. My father was a World War II veteran. My mother stayed home

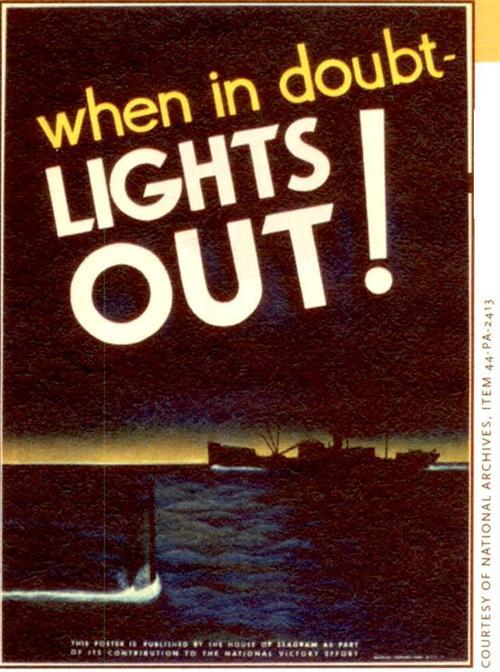

war time

Understanding the times your family lived through — such as the fear of attacks during World War II — gives you a better glimpse of their experiences.

to raise me. We lived in a 1940s development of San Francisco, the Outer Sunset District. Our house was a row house, attached to the neighbors’ houses, with its duplicates strung for miles up and down city streets. Of course my father had used his GI loan. He came home tired every night from his role as the breadwinner. I have in my possession the well-worn copy of Dr. Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Child Care (1946) by which my parents raised me.

Try this exercise about yourself and your parents. Write it out. When you stop, you’ll have created your own family history document worth keeping, so note the date, place and your name on it for posterity.

on the bookshelf

• Bringing Your Family History to Life through Social History by Katherine Scott Sturdevant (Betterway Books, $19.99)

• Generations: Your Family in Modern American History by Jim Watts and Allen F. Davis (McGraw-Hill, $45.80)

• Nearby History: Exploring the Past Around You by David E. Kyvig and Myron Marty (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, $24.95)

• Your Family History: A Handbook for Research and Writing by David E. Kyvig and Myron Marty (Harlan Davidson, $8.95)

General Social Histories

• Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America by David Hackett Fischer (Oxford University Press, $27.50)

• As Various as Their Land: The Everyday Lives of Eighteenth-Century Americans by Stephanie Grauman Wolf (University of Arkansas Press, $15)

• Domestic Revolutions: A Social History of American Family Life by Steven Mintz and Susan Kellogg (Free Press, $13.95)

• Everyday Life in Early America by David Freeman Hawke (HarperCollins, $13)

• The Expansion of Everyday Life, 1860-1876 by Daniel E. Sutherland (University of Arkansas Press, $15)

• Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era by Elaine Tyler May (Basic Books, $20)

• The Reshaping of Everyday Life, 1790-1840 by Jack Larkin (HarperCollins, $14.50)

• The Uncertainty of Everyday Life, 1915-1945 by Harvey Green (University of Arkansas Press, $15)

• Victorian America: Transformations in Everyday Life, 1876-1915 by Thomas Schlereth (HarperPerennial, $15)

Model Family History Narratives

• Defend the Valley: A Shenandoah Family in the Civil War by Margaretta Barton Colt (Oxford University Press, $17.95)

• The Hairstons: An American Family in Black and White by Henry Wiencek (Griffin, $14.95)

• Homelands and Waterways: The American Journey of the Bond Family, 1846-1926 by Adele Logan Alexander (Vintage, $16)

• A Scattered People: An American Family Moves West by Gerald McFarland (Ivan R. Dee, $16.95)

• Slaves in the Family by Edward Ball (Random House, $15.95)

• Stubborn Twig: Three Generations in the Life of a Japanese American Family by Lauren Kessler (Dutton/Plume, $20)

A social historian would analyze home sources as primary sources for clues to everyday life. So gather information in your own household and family to put your family history in context: artifacts, photographs, oral history interviews, correspondence and even handed-down stories. Think of even the mundane things around you (and around your ancestors) as artifacts that reveal social history: tools, utensils, furniture, clothing, food, memorabilia.

Suddenly these matter in a more serious way because you aren’t using them for mere facts. For example, genealogists know that oral accounts are liable to be factually unreliable. But now you’re after exactly those biases, versions, feelings and recollections that make good stories but poor genealogy. As long as you present this material as just what it is — Aunt Josie’s version — you’re also being meticulous in your standards. Here’s an example of what you could write in a family history narrative using dubious or conflicting testimony:

Josephine always claimed that Mary gave birth to her first son on Nov. 10. Mary herself insisted it was Nov. 9. The birth certificate agreed with Mary, and who should know better than the mother? Aunt Josie, however, later said, “My sister was out of her mind with pain and didn’t look at no calendar for two days. I did.”

Similarly, don’t think of photographs as just lifeless illustrations for a separate section of your family history; use them to illustrate a point in your narrative, or even describe the photograph as part of your text. If you don’t have suitable family photographs, think as a social historian would about illustrating a point: If you’re describing frontier forests and plains, go to a historical archive and find pictures of them. Don’t have a photo of your great-grandfather in uniform? Find one like it in a historical society’s archive.

The same is true for family heirlooms. Think like a social historian: Do some historical research to determine their age and use. Describe how your family probably used them, perhaps with an illustration. If you don’t have your own family’s artifacts, you can figure out what people like them owned and find illustrations in social history books.

HIT THE BOOKS

Dozens of books can help you discover the social history of your ancestors’ times and put meat on the bones of your past. See the box on the opposite page for some starting points. For example, Mintz and Kellogg’s Domestic Revolutions is a description and analysis of family life throughout American history. Try reading about your or your parents’ decades in it and you’ll begin to see how much of the general context fits individual lives.

The same will be true as you push backward in time. Whenever you set out to do historical research, formulate your question to cast a broader net. For example, say your ancestors were Norwegian farmers in a Wisconsin village. Rather than looking for the proverbial “book on my family,” search for books on that village, on farming in that region and on Norwegian immigrants.

As you explore the bookshelves, keep these tips in mind:

• Take thorough notes or make photocopies of what you find.

• Keep track of complete source citations.

• Keep an open mind about what life was like back then — never assume that you already know.

• Don’t dismiss something interesting as too minor or frivolous for historical study. If you wonder about it, some historian probably did, too — and wrote a book or article about it.

• Expect complexity. People rarely acted on one singular motive, and there’s more than one side to every story.

• Always try to see your ancestors as members of groups and examples of larger-scale social behavior. Watch for patterns.

• Think like a sociologist as well as a historian. Sometimes you need to be “clinical” as well as objective to handle closet skeletons and past controversies.

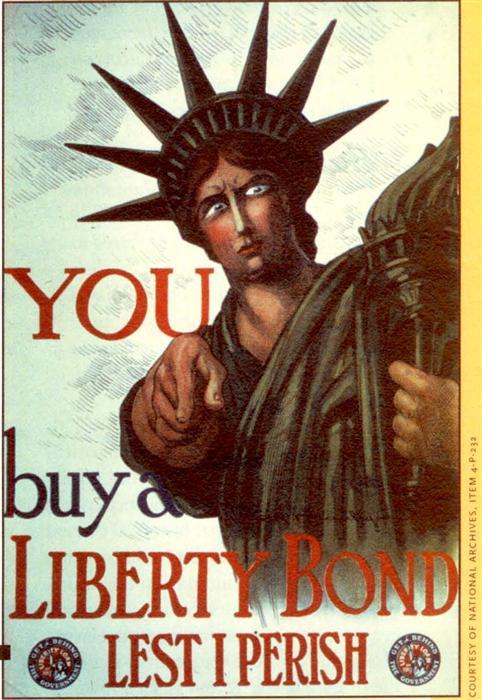

economy

The economy’s ups and downs throughout history may help explain your ancestors’ financial situation, such as why they bought government bonds.

find it on the web

• The Making of America

<moa.umdl.umich.edu>: Collection of primary documents in American social history from before the Civil War through Reconstruction.

• American Social History Project

<www.ashp.cuny.edu>: Presents “Who Built America?,” both an excellent textbook of American social history and a collection of documentary films with a social history perspective.

• American Memory Project

<lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem>: Digitized collection of American history documents from the Library of Congress.

• PBS History Page

<www.pbs.org/history/american.html>: Leads you to PBS’ many American history programs, notably “The American Experience.”

PUT IT ON PAPER

The best thing to do with the social history information you find is to weave it into your own family story. Whether you write it down just for yourself and your descendants or for the whole world, it’s important to record your findings. And you don’t have to be a great writer to have your family history narrative appreciated — don’t you wish that your ancestors had written down their stories, however crudely?

Here are some suggestions for weaving together family and social history on the page:

• Keep track of chronology as you go. History is dynamic. It is about change over time.

• Refine your “switchbacks.” You’ll be writing from the particular (your family) to the general (society) and back again. That means transitions, one of the trickiest pieces of writing to do. Here are two examples of flowing from precise family information to the general social history and back again, to give you an idea:

Charles Gottlieb claimed a homestead in western Nebraska in 880. There were many German immigrants in the area, so they were able to maintain a German Lutheran Church, and to conduct services as well as everyday business in German.

After the Civil War, it was a constant frustration for Southern plantation ladies to try to locate “good help.” The former slave women preferred to make their own homes and do their own cooking for their husbands and children. So it was fortunate for Susan Tucker when she located a maid who would last 10 years in her household.

• Avoid “Titanic Syndrome.” This means don’t insert famous historical events that are irrelevant to the family story. Students in my family history college classes tend to think that historical context means simply throwing bits of history into their genealogical summaries; they think of history as famous names, dates and events. So they insert strangely irrelevant historical facts into their family stories — the sinking of the Titanic is their favorite.

One side effect of Titanic Syndrome is that when the relevance of the historical interjection isn’t obvious, readers imagine it, which can sometimes imply a causal relationship that’s downright funny! For example:

Mother was born in 1912. Two days later the Titanic sank.

The Titanic sank when Robert and Theresa got married.

My baby sister was born May 6, 1945. Two days later, the Nazis surrendered.

Tom celebrated his birthday and then the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

• Avoid anachronisms, things out of their proper historical place, such as a microwave oven in a colonial kitchen. Make sure of what really fits the times.

• Never fictionalize unless you’re openly setting out to write a work of fiction. Once you leave doubt about the reliability of your information and conclusions, doubt spreads.

• Don’t be embarrassed by skeletons in the closet. I believe “no pride, no shame; no credit, no blame.” You aren’t to blame for your ancestors’ transgressions any more than you can take credit for their accomplishments. Instead of pride or shame or even sympathy, try to write with “historical empathy” for your ancestors. As you learn about their lives and times, you walk miles in their shoes, imagine what they felt and, through history, experience that “relationship” we seek in family history. Historical empathy means experiencing it more deeply, as though you are your ancestors.

Remember, the social history of your people was, after all, their world. Preserving their names and dates without it is taking them out of context. With the help of social history, you can put them back where they belong.

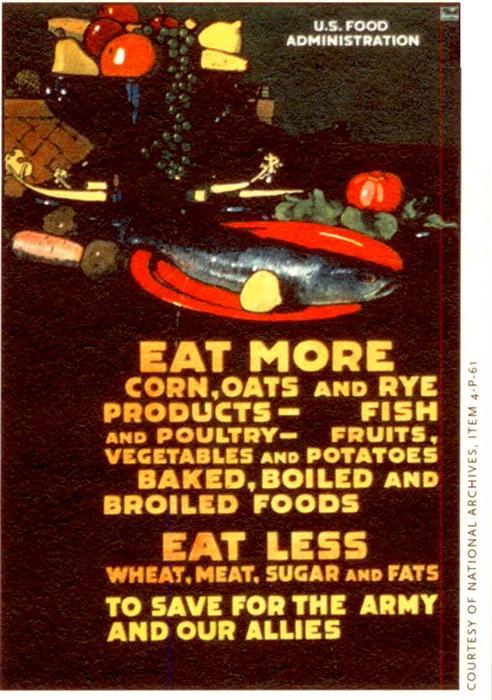

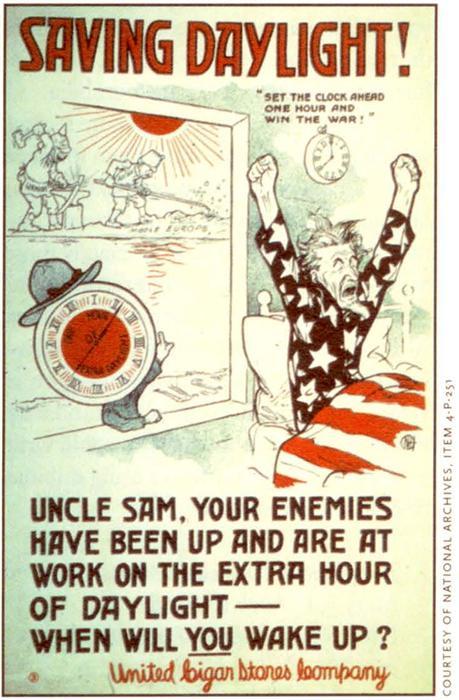

conservation

Did your family scrimp on meat and sugar or set their clocks ahead during World War II? Weave these aspects of history into your own family story.

KATHERINE SCOTT STURDEVANT is the author of Bringing Your Family History to Life through Social History (Betterway Books, $19.99), upon which this article is based. She has taught college history for more than 17 years, family history for 10 years, and teaches classes in writing family and personal memoirs for WritersOnlineWorkshops <Error! Hyperlink reference not valid.>.

ADVERTISEMENT