Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The US government issues official passports to certify the holder’s identity and citizenship or legal resident status. It entitles the person to travel internationally under US government protection. Citizens as well as non-citizen nationals who legally reside in the United States are eligible for passports:

During the American Revolution (1775-1783), consular officials issued passports valid for up to six months. Passports weren’t required for travelers between 1783 and 1789, although the Department of State, states, certain cities and notaries public would issue them. Not until 1856 did Congress enable the Department of State exclusively to issue and regulate passports.

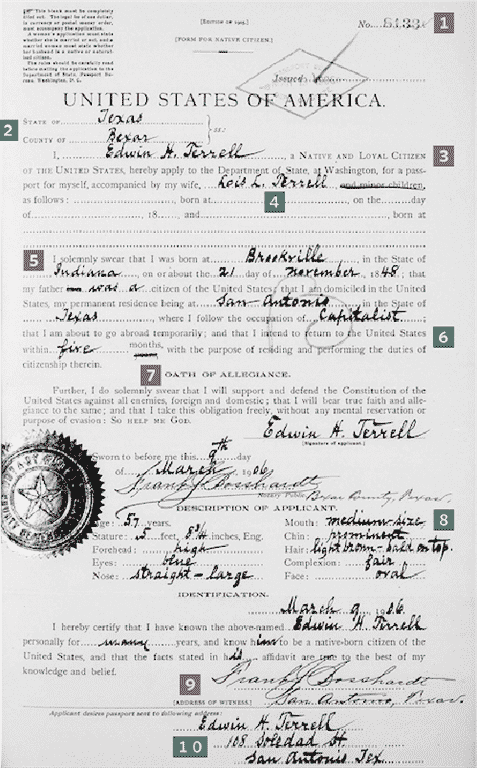

Different passport applications were used over time, with later forms requesting more information. Early passports are handwritten, containing various wordings. Later, preprinted forms standardized the verbiage. By 1888, native, naturalized and derivative (women and children who became citizens when the husband or father naturalized) citizens used separate application forms. Still later forms included the applicant’s photo. Supporting documents, such as letters and signed affidavits, were sometimes submitted with the application. View the actual application, rather than rely on an index, to see such documentation.

Passport applications from 1795 to 1925 are accessible on National Archives microfilm (series M1372 and M1490) and online. You can search them by name and view record images on Ancestry.com. FamilySearch.org also has the images, but they’re not yet indexed by name.

- The processing office assigned a certificate number. It may not be present on early passports, but if there is one, record it in your source citation.

- The state and county where the application was made isn’t always where the applicant lived at the time.

- The verbiage immediately following the applicant’s name indicates the person’s citizenship status—natural born (“native”), naturalized or derivative. The latter two designations are clues to seek naturalization records.

- The application may name a wife and minor children accompanying a male traveler. The children’s places and dates of birth also will be listed.

- Passport records are a good source for the applicant’s date and place of birth, especially for immigrants. Depending on the form used, you also may learn the person’s place of residence and citizenship status of his father.

- On later forms, the applicant provided information about his intended destination and length of the trip. His return to the United States would be recorded in passenger lists, along with the names of immigrants.

- The applicant’s signature provides a sample of his handwriting; compare it to the rest of the form to help you determine whether someone else filled it out (introducing an opportunity for error).

- Wonder what your ancestor looked like? The description of the applicant assisted in identification. Later forms may include a photograph.

- A witness—in this case, the notary public—attested to knowing the applicant. The witness may be a friend or relative, worth researching as part of a “cluster” strategy.

- The address to which the passport should be sent may be the applicant’s place of residence.

A version of this article appeared in the October/November 2014 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT