Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

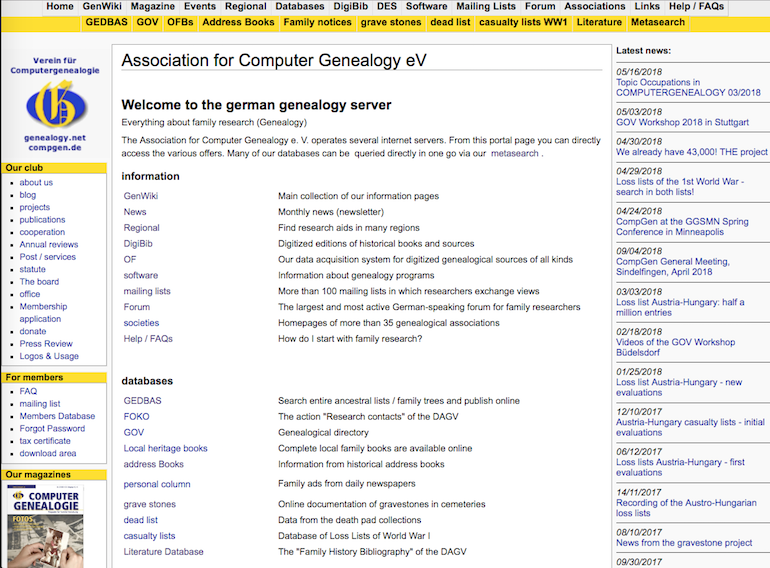

When it comes to family history, tapping into local expertise is one of the best ways to get the deepest and richest research results. For those with German-speaking ancestry, acquainting yourself with the free website known variously as Genealogy.net, Compgen.de or Genealogienetz.de can be your best shot at connecting with records, people, genealogical societies and other resources in Germany.

The site was created by bona fide German genealogists, in German, but much of its content is available in English (and translation tools help with the rest). You don’t even have to register to get results in its research wiki, pedigree database, digitized documents and more—though setting up a free account does come with benefits. Let’s show you what German genealogy features the locals fancy at Compgen.de.

See Compgen.de in action in this video tour:

Getting started on Compgen.de

First, about the name: This mega-site is run by the Verein für Computergenealogie e.V., which translates as the Society for Computer Genealogy, Inc. It’s Germany’s largest genealogy group at about 3,600 members. Digital geeks that they are, they’ve secured the most relevant URLs to lead more researchers with German roots to the site. For our purposes, we’ll call the site Compgen.de. Volunteer Timo Kracke, a self-described tech guy and Computergenealogie society board member, does a lot of the site’s heavy lifting. (You can access his presentation about Compgen.de to the Anglo-German Family history Society by scrolling to the bottom of this page)

In terms of language, Germany-based websites fall into three categories. Some give full English translations of everything on the site, and some are only in German. And many sites, including Compgen.de, partially translate or summarize the German. For these last two types, most computers and browsers now offer the ability to right-click (or control-click, on a Mac) on the web page and select Translate to English from the popup menu. If the “right-click trick” doesn’t work for you, either visit the site in the Google Chrome browser for the option to view a translation, or plug the site’s URL into Google search and use the “Translate this page” link. Keep in mind these options also translate some place names and surnames—for example, the name Langen may become “long;” Baum, “tree.” If this happens to your names, use the German and English versions together.

Perks of registering

Compgen.de doesn’t require you to register, but if you do (have we mentioned it’s free?), you can post questions to the site’s forum and upload public family trees. The site’s array of genealogy offerings is grouped into a two big menus, listed on the home page):

- Information (Informationen): Find background on German history and archives, with links to many regional family history groups and repositories.

- Databases (Datenbanken): Search a number of databases for records of people and places.

- Databases (Datenbanken): Search a number of databases for records of people and places. As you get familiar with Compgen.de, you’ll find there usually are at least two ways to find every database or list. We’ll use the most direct way on our tour of the local gems that make up this site.

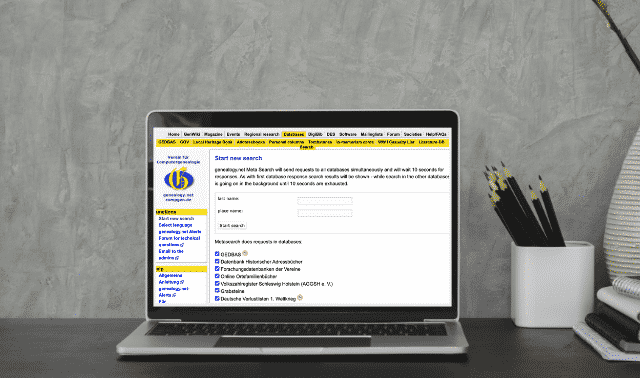

Metasuche: Searching the full site

You might be thinking that a big site like Compgen.de could use an all-inclusive search function. And it does indeed have one. It’s called Metasuche (“big search”), available via a link at the top right of the site or by going to meta.genealogy.net. You have the option of searching with a surname or a place name or both.

This is a timed search of all of Compgen.de’s databases at once—family trees, address books, local heritage books, tombstones, newspaper notices, World War I loss lists and more. Click the Datenbanken link to see them all and read their descriptions. On your results page, Metasuche indicates which of the databases successfully responded. Below that are the findings in a chart, with columns for the name of the database, last name, first name, and details from the database listing. Click on the name to see the full database entry. In addition, some of the databases support an “alert” function, for which registered users can receive notification when a database adds info that matches the search.

Refining your search within databases

Now, the crucial caveat about this search is that’s it’s not an all-you-can-eat buffet: It times out rather quickly, meaning that all the databases might not be completely searched. To get more results, you can uncheck databases you don’t think will be helpful before you click Start Search. Otherwise, once you go through your Metasuche results, you can partake of individual databases.

Continue reading to learn more about these databases, and access them either through the navigation links in the site’s yellow bar or on the Datenbanken landing page. Following are our recommended bites from the Compgen.de menu:

GEDBAS

Another database serving from Compgen.de is GEDBAS, which contains family tree data uploaded by users as GEDCOM files. The database is similar to public trees on familiar sites like FamilySearch, Ancestry and MyHeritage. Keep in mind the information isn’t independently verified, and you’ll want to research the claims before adding the data to your tree.

GEDBAS lets you search millions of pedigree-linked individual profiles from a few thousand family trees. Start by clicking GEDBAS at the top of the home page. You can enter surnames, first names and place names, and optionally specify files added within the last week, month or year. When a search comes back with hits, it gives the first name and surname of the person in the database, along with birth and death years if known. Clicking the person’s name takes you to the full database listing, which may provide dates and places of birth, marriage and death; occupation; and names of family members. You also might learn the name and email address of the person who added the data, and when he or she added it. Clicking the link (if available) to “Show all persons of this file” will display all the names uploaded at the same time.

This database is continually expanding and is worth checking back if you don’t initially find anything. If you register for the site, you can save time by setting up an alert to notify you of new matches to your search.

GenWiki

The GenWiki (accessible under Informationen on the home page) is like a sampler platter, offering portals to additional information and databases. It contains Wiki articles with history, links to repositories serving German areas, links to dictionaries, and other genealogy helps.

There’s also an English version of GenWiki, but note that it’s not a full translation—it contains much less information than its German-language counterpart. The best strategy for using GenWiki, therefore, is to use the German version with the aforementioned right-click trick or Google’s “translate this page” feature.

The wiki’s Regional Research (Regionale Forschung) section serves up Compgen.de at its best, offering hundreds of articles on basic history and political jurisdiction of areas (either in Germany or a place that had a German-speaking enclave) or topics like coats of arms and rulers of the former German microstates. Try entering the name of your ancestor’s hometown, district or German state in the Search in GenWiki (Suche im GenWiki) box at the top left. You may then need to select from similarly named places. For example, enter the town Steinfeld, choose Steinfeld (Oldenburg), because it was located in the Duchy of Oldenburg, and you learn the district (landkreis or kreis) and state (land or bundesland). The wiki gives the years of coverage for Catholic church books, the name of the church, a link to the local diocese, and a map. It also recommends books and a local genealogy group, and lists related places, such as the district Steinfeld is in and nearby towns.

You also can search the wiki for a place and the word history, a family name, a historical event or an unfamiliar term.

Local History Books

Under the heading OFBs, you’ll find a collection of particular interest: the Orsfamilienbücher (also called Ortsippenbücher, both of which translate roughly as “community genealogical history books”). Many OFBs are a by-product of the Nazi era: In the 1930s, as the German citizenry were prodded into proving their Aryan heritage, people extracted church and other records onto index cards for easy access.

After World War II, these card files were used to compile village or community histories, family by family, in OFBs. The books review families alphabetically, giving each family a number. There’s an additional family number for each person (parent, child, spouse) whose information continues elsewhere in the volume.

Compgen.de has more than 600 searchable OFBs—a huge increase in accessibility, as just a few libraries in America have large collections of print OFBs. Compgen.de has OFBs from all parts of Germany, but Hesse and the Hannover area are especially well-represented. The OFB landing page has a clickable map; below that, find a listing of villages (organized alphabetically by present-day German states).

When you click on the OFB for a village (whether from the map or the village listing), you get a historical summary of the village with links on the left-hand side. Click a link to the complete list of family names for a directory, then click the first letter of the family name. You can then click a surname, then a particular person, to see other names associated with that person, such as a parent, spouse or child. The clickable names eliminate the need for the print OFBs’ family numbers.

The amount of information about each person varies with what was found in the original record. OFBs enjoy a good overall reputation for accuracy, but you’ll want to research further in the church or civil records from which the book was compiled.

GOV

Genealogisches Ortsverzeichnis (“Historical Gazetteer”), nicknamed GOV, is a village gazetteer that covers much of Europe with more than a million entries. Put any place name into GOV and, if it’s spelled right, the database returns any listings for that place name. Note that many German towns are duplicated in GOV, with separate entries for religious and civil data. Choose the right place from your results list to see a map and learn details such as the church or parish (with Protestant identified by ev for evangelisch, and Catholic by rk for römisch-katholisch).

Part of a GOV entry is a graphic called Übergeordnete Objekte (“Parent Objects”), which traces the history of the place over time to show which larger political units it was part of. Because of Germany’s “nonlinear” history—it was carved up into hundreds of micro-states, which were sliced and diced repeatedly over the centuries—this graphic can help you figure out which place’s archives might have records relating to the specific village over time.

A drawback to GOV is that the place you enter must be spelled exactly right—no similar spellings or sounds-alike searches allowed. A workaround for villages of the Second German Empire (1871-1918) is to first do any phonetic searching in the online Meyers Gazetteer.

DigiBib

If Compgen.de offers a house delicacy, it’s DigiBib, short for Digitalen Bibliothek (“Digital Library”). It’s exactly what it sounds like: digitized out-of-copyright books from German libraries. Under the Themengruppen (“Themed”) heading, click Alle bücher (“All books”) for a list of digitized titles. This collection is growing by leaps and bounds, and site managers aim to transcribe the books to make them word-searchable and downloadable as e-books.

But Digibib can start fortifying your family tree now with its large collection of Adressbücher or German city directories, useful for tracking urban Germans year by year. DigiBib is larger, than Compgen.de’s separate database of Adressbücher, so you should check both places for such residential lists.

Vereine

Think of Vereine (“Societies”) as dessert. Really, it’s a whole dessert tray, delivering access to dozens of German genealogical organizations’ websites. We said that local expertise is crucial, and this is the proof in the pudding.

Some of these society websites have databases, including a few relating to immigration, and most offer contact points that nonmembers can use to ask questions about local records. For Steinfeld, for example, you’d want to explore the websites of the Oldenburgische Gesellschaft für Familienkunde (with a focus on the former Duchy of Oldeburg) and the Niedersächsischer Landesverein für Familienkunde eV (for research in Niedersachsen). Click the GenWiki link to learn more about the group and on the group name to visit its website.

While it’s not assured that every genealogy organization will give free or quick assistance—members are volunteers, just like their US counterparts—they’re often motivated to connect with the descendants of their families’ emigrants from Germany. German genealogists’ desire to work cousins’ family trees forward and backward in time can allow you to leverage their knowledge of books and other resources available only in Germany. Truly, the Vereine section of Compgen.de might make you want to eat dessert first.

German Genealogy Societies on Compgen.de

The site’s growth is due, in part, to numerous regional German genealogy associations teaming up with Compgen.de/Genealogy.net—and these groups are often expanding the databases and services they offer. Here, I’ll share two quick success stories of researchers using these partnerships to discover information about their ancestors.

Verein für Familienkunde in Baden-Württemberg e.V.

One researcher, Dick Wirtenson, knew his ancestor hailed from a town named Hochdorf in Württemberg, but had also heard of an even smaller town called Benzenhaus. Wirtenson wanted to learn more about this Benzenhaus, so he went to Genealogy.net and discovered a branch of the Verein für Familienkunde in Baden-Württemberg e.V. for that part of Württemberg (the district of Biberach). (Baden-Württemberg is the current southwest German state that encompasses the former smaller states of Baden, Württemberg and Hohenzollern.)

Wirtenson e-mailed the Biberach group and was rewarded with a reply from one of its members. The member found a publication that stated the father of Wirtenson’s immigrant ancestor aided a gang of robbers and served four-months’ jail time as a consequence. Assuming the story is true, Wirtenson had found a rich family story from records that are not online or available in America!

Oldenburgische Gesellschaft für Familienkunde e.V.

In a similar way, researcher Mary J. Lohr learned about the Oldenburg emigrant database, a project of another German regional group, Oldenburgische Gesellschaft für Familienkunde e.V. The Oldenburg group, which Lohr learned about from Trace Your German Roots Online, focuses on the part of the modern German state of Lower Saxony (in German, Niedersachsen) that was the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg during the German Second Empire (1871–1918). The group’s emigrant database contains thousands of names from a variety of sources of those who left the grand duchy, mostly in the 19th century. In addition to the emigrant’s names, the database often includes birthdates and places, places of settlement after emigration, and names of other family members (if known).

By consulting this resource, Lohr discovered a new score of records that she wouldn’t have had access to otherwise, opening up infinite new research possibilities.

To look through all of the societies linked to Genealogy.net/Compgen.de, go to the site’s Regional page. An English version of any site is available by cutting and pasting the URL of the German site into a Google search, then choosing “Translate this page” from the search results. (Note: The site has an organic English version as well, but the English side of the site has fewer resources than the German side.)

A version of this article appeared in the October/November 2018 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT