Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Even if your ancestors didn’t settle in Noodle, Dime Box, Ding Dong or Bugscuffle when they got to the land of the Lone Star, they may have scrawled farewell notes on their doors back east saying “GTT” — Gone to Texas. Enthusiasm for going to Texas was especially strong following the US economic panic of 1837 and after the Civil War. Texas didn’t offer the gold panning or fur trapping that lured so many folks farther west, but it had land — lots of land.

Changin’ the flags

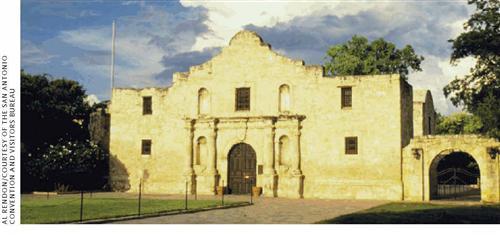

Depending on when your ancestors arrived, they may have lived under one or more of the six national flags that have flown over Texas. First was the Spanish flag from the 16th to the early 19th centuries. Besides exploring for gold that wasn’t there, Spanish priests and soldiers tried to introduce Christianity to the native people through a chain of missions and presidios (forts). Modern cities that emerged from such Spanish settlements include El Paso (1682), San Antonio (1718) and Nacogdoches (1779). French claims to the area (the second flag) in the 1680s briefly threatened Spanish control.

When Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, Stephen F. Austin and other empresarios negotiated colonization contracts with the Mexican government (the third flag) to settle hundreds of American families in Texas. These colonists were eager for chunks of cheap land with virgin soil for cotton and food crops, and prairie grasses for grazing livestock.

By the 1830s, the Americans’ relations deteriorated with the Mexican government over its attempt to halt Anglo-American settlement. The Mexican army’s move into Texas in early 1836 alarmed “Texians,” who organized a provisional government that declared independence on March 2. When the short revolution ended with victory at San Jacinto, settlers hailed the Lone Star flag of the new national government, the Republic of Texas. The republic lasted through 1845, when the US Congress annexed Texas as the 28th state and the Stars and Stripes became the fifth national flag to fly over the land. During the Civil War, the state flew its sixth banner — that of the Confederate States of America.

Before the Civil War, new arrivals came largely from the US South, with a sprinkling from other states. German, Mexican, Polish and Irish settlers (among other Europeans) added to Texas’ diversity. The late 19th century witnessed the heyday of the cattle kingdom and the establishment of ranching as a leading industry in the state. A major oil discovery at Spindle-top, near Beaumont, in 1901 added another important dimension to the economy. Contrary to rumors, not all Texans live on ranches or own oil wells, but most feel the impact of these two historical developments.

Explorin’ the records

The state that offered lots of land offers lots of family history records, too. Among those you’ll want to corral:

• Censuses and substitutes: The first federal census for Texas was taken in 1850. Although fire destroyed most of the 1890 census, schedules survive for a few families in Ellis and Trinity counties and a handful of other Texans. The 1890 census of Union vets and widows also exists for Texas. Find census records at the Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org>, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) <archives.gov> and many libraries, or online at Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > (by subscription or free at subscribing libraries) and HeritageQuest Online <heritagequestonline.com> (free through subscribing libraries).

Several town censuses from the 1830s name heads of household and family members. One abstract of these lists is The First Census of Texas, 1829-1836 (see resources), available in many libraries and on microfilm at the FHL and its branch Family History Centers (FHCs). Use the FamilySearch Web site to locate an FHC near you.

Texas has taken no state censuses, but some school enumerations exist for 1854 and later, depending on the county. Some of these records are in county courthouses. For microfilm, check the FHL online catalog.

To track your Texas ancestors with or without censuses, consult county courthouse records, city directories (generally starting post-Civil War) and annual tax rolls (which date from 1837 for most original counties). Microfilmed tax records through 1910 are available at Houston’s Clayton Library, the Dallas and Fort Worth public libraries (see resources) and the FHL, but not through FHCs. Other public libraries have the rolls for their counties. Many county records and tax rolls, along with other Texas records, also are available on microfilm through the Texas State Library and Archives Commission’s (TSLAC) interlibrary loan program <www.tsl.state.tx.us/arc/local>.

For studying early Lone Star residents, 1835-to-1846 Republic of Texas claims — citizens’ requests for payment or reimbursement from the government — are an important resource. You can search for and view digital images online at <www2.tsl.state.tx.us/trail/RepublicSearch.jsp>, or borrow microfilm from TSLAC. Voter registration lists from 1867 to 1869 often give the person’s birthplace, naturalization information and length of residence in the county and state. These lists are on microfilm at TSLAC, the Clayton Library and the Dallas and Fort Worth public libraries.

• Vital records:Nineteenth-century vital records exist for some cities, but statewide birth and death records began in 1903. Although the state bureau of vital statistics (see resources) holds the statewide records, you can get copies more quickly from the county clerk where the event occurred. For delayed birth certificates, try the county of birth. TSLAC has some microfilmed birth and death records; microfilmed death certificates also are available at some libraries, including the Clayton Library and Dallas and Fort Worth public libraries.

Most marriage records are at the county clerk’s office or on microfilm via TSLAC and the FHL. Although statewide marriage records began in 1966, you can get certified copies only from the county clerk’s office that issued the license. Statewide divorce records date from 1968, but copies of divorce decrees come only from the district clerk’s office where the case was heard.

• Military:Request copies of Confederate or Union Civil War service records from NARA <archives.gov/genealogy/military> or rent microfilm copies from the FHL. In 1899, Texas began authorizing small pensions for indigent or disabled Confederate veterans or their needy widows. An index and instructions for obtaining copies are online at <www.tsl.state.tx.us/arc/pensions>. These records may provide age, marriage information, length of residence in Texas, the nature of the need or disability and information on Civil War service. You’ll find an index of indigent families of Civil War soldiers at <www.tsl.state.tx.us/arc/cif>.

TSLAC holds the state adjutant general’s Republic, Civil War and later records; for information, visit <www.tsl.state.tx.us/arc/findingaids/recordsfindingaids.html>. An index of the adjutant general’s military service records (1836 to 1935) for Texas Revolution soldiers, Republic army and navy, state militia, rangers and others is at <www2.tsl.state.tx.us/trail/ServiceSearch.jsp>. For WWI vets — even those whose service records burned in a 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis — contact the Texas Military Forces Museum (see resources) for a copy of a service card. The museum’s WWI card file summarizes Texas vets’ enlistment, service and discharge information.

• Land: Seeking Spanish, Mexican or Republic of Texas grants, land-hungry settlers saw opportunity in Texas. The Congress of the Republic granted land from its millions of acres to single men and heads of families, with the amount of land based on their arrival dates. Soldiers in the Texas Revolution were eligible for additional acreage, and new military recruits often were promised bounty land for their service. Search for land grants and view some digital images (as well as order copies) from the state’s General Land Office at <www.glo.state.tx.us/archives/landgrant.html>. These grants were the first transfer of land from government to individuals. Subsequent transactions are recorded in county deed books, some of which are on microfilm at the FHL and TSLAC.

More than 40 Texas county courthouses have lost records in fires and storms. When one of your ancestral counties is a “burned county,” you still can research with local, state and federal records, surviving or re-recorded county records, and those of neighboring and parent counties. (See the 2006 Genealogy Guidebook, a Family Tree Magazine special issue, for tips.) So don’t be buffaloed about your Texas ancestors. Y’all come, sit a spell and enjoy the many resources of the Lone Star State.

From the October 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT