Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

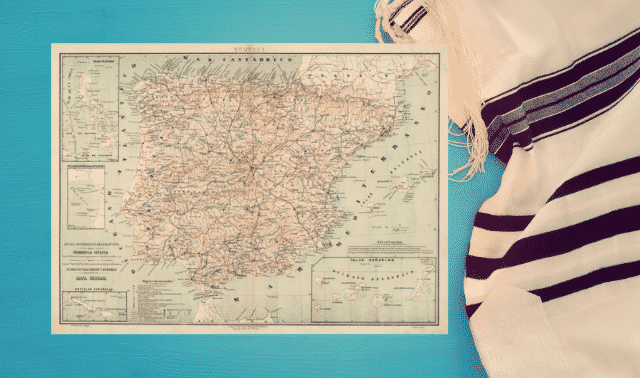

After their eviction from Spain, Iberian Jews had three choices: Convert (those who did were called conversos), pretend to convert and secretly practice Judaism (marranos) or leave the country. (Please note the pejorative term marranos refers to swine and is no longer used.) Those who fled repatriated in Muslim nations, particularly in the Ottoman Empire, where Jewish exiles were welcomed with open arms.

The Sephardic label originally referred only to Jews expelled from Spain following that country’s 1492 Inquisition, but the term is often used to describe Jews from the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. In recent years, the definition has expanded again to include all non-Ashkenazic Jews. For genealogical purposes, Sephardim are often defined as Jews of Iberian, Italian and North African ancestry.

Familias viejos and Conversos

To avoid further threat of persecution, many secretly-practicing Jews jumped at the opportunity to start a new life in the Americas. Thanks in part to DNA research, a large number of Latinos are finding connections to the familias viejos—the first families in what’s now the US Southwest. Many old New Mexico families in particular descend from conversos who arrived with Juan de Oñate and other explorers. Conversos also are called bnai anousim—Hebrew for “children of the forced.” Some families have preserved knowledge of their Jewish pasts and observe certain traditions, such as lighting Friday night candles and adhering to dietary rules.

If you suspect your family might descend from conversos, start at the Society for Crypto Judaic Studies. Search the passenger lists of Spaniards who left for the Americas preserved in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain. Besides listing all passengers who sailed to America up to 1800, records may provide such data as birthplace, parents’ names, occupation and destination.

Written by Schelly Talalay Dardashti

This information appeared in the September 2006 issues of Family Tree Magazine.

Finding your Sephardic Jewish Ancestors

Many Sephardic Americans are relatively recent immigrants from Israel and Muslim lands who came starting in the late 1960s. But some Sephardic Jews came to the New World to evade the Spanish Inquisition. For these two groups, available US immigration records — largely from the 19th and early 20th centuries — won’t be of much use. Sephardic genealogists must instead turn to less-mainstream research techniques.

Breaking one of genealogy’s cardinal rules — working backward — may prove useful because Sephardic Jews with similar family names likely have a common ancestor before the Inquisition. Jeff Malka, author of Sephardic Genealogy (Avotaynu), has compiled a list of common Sephardic surnames. The Sefard SIG provides a wealth of information on researching Sephardic roots. The International Sephardic Leadership Council plans to add a genealogy research center to its Web site this year.

Documents from the Inquisition and prior eras are spotty. Although a smattering of records from the expulsion exists, few records were kept, much less preserved. “When Ferdinand and Isabella forced everyone to convert, they didn’t really write it down,” says Gary Mokotoff, founder of Avotaynu.

Sephardic Names and Surnames

Whereas Central and Eastern European Jews adopted surnames en masse in the early 19th century, many Sephardic Jews’ surnames date as early as the 12th and 13th centuries. So family names are much more important to Sephardic genealogists than to Ashkenazim.

Additionally, knowing traditional naming conventions is essential to tracing your Sephardic ancestry. Unlike Ashkenazic Jews, who generally name children after deceased relatives, Sephardic Jews often name their children after living grandparents. Oldest sons are named after the paternal grandfather, oldest daughters after the maternal grandmother, and so on. These patterns give clues to family relationships that can help you make sense of your family tree.

Written by Etan Harmelech

This information appeared in the August 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT