Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Even though the Soviet Union disappeared from the map more than a decade ago, the specter of communism remains hard for its successor countries to shake — especially in America. Our perceptions of Russia still gravitate toward the Cold War rivalry, from spy-novel plots to the 1980 US hockey team’s “miracle on ice.”

The frosty US-USSR relationship certainly hasn’t faded from family historians’ memories. Nearly 3 million Americans have roots in Russia; another 1.5 million-plus claim ancestry in Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. For decades, those who wanted to discover their family’s past faced the ultimate brick wall: the iron curtain.

After the Soviet Union dissolved, it became easier for Americans to visit their Eastern European ancestral homelands. Opportunities for actual genealogical research have been slower to develop, though. New governments meant new jurisdictions for archives. Amidst the reshuffling, genealogists have overwhelmed archives in the former USSR with research requests. But archivists haven’t leapt to keep pace with the new demand for their services — old ways of thinking linger on the other side of the ocean, too. Miriam Weiner, president of Routes to Roots <www.routestoroots.com>, a travel and research firm operating in the former Soviet Union as well as Poland, says these countries have only recently begun to understand genealogists’ interest and recognize the potential income from family history research.

Communist-era complications aren’t the only challenges you’ll face. Even basic questions, such as where your ancestors came from, might not have cut-and-dried answers. Before the USSR, the now-independent republics were part of the Russian Empire. So “Russian roots” encompasses far more than the present-day country. “Russian is often used as a generic term to describe people of widely varying ethnic backgrounds who have come to the United States from lands that were once part of the Russian Empire or … the USSR,” explains Eastern Europe scholar Paul Robert Magocsi. Ukrainians and Belarusians were often lumped in with Russians, for example. In fact, most immigrants from Russia weren’t ethnic Russians: More than half were Jewish; another fifth were Poles and Germans.

These obstacles make tracing your roots tough — but not impossible. To uncover your family’s history back in the former USSR, you’ll need luck, expert help and an understanding of the region’s past.

Tracing Russia’s roots

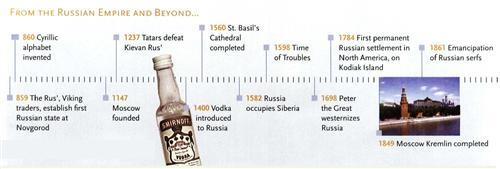

The name Russia conies from the Rus’, a 9th-century tribe of Scandinavian merchants and warriors. They built Kievan Rus’, a state that encompassed Ukraine, Belarus and European Russia. Kievan Rus’ lasted through the 13th century, until Tatar invasions reduced the empire to Moscovy, a duchy centered around Moscow. Moscovy’s goal became reuniting the lands of Kievan Rus’.

By the 15th century, Moscovy was fending off not only the Tatars, but also the Lithuanians. At its height, the powerful Lithuanian empire included Belarus, most of Ukraine and part of Russia. A royal marriage united Lithuania and Poland in 1389; in 1569, the countries merged entirely, creating a Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth known as the Rzeczpospolita. Ivan “the Terrible” became Russia’s first czar during the mid-16th century; his rule was followed by the “Time of Troubles,” a period of internal anarchy and foreign invasions.

After the famous Romanov dynasty took hold in 1613, Moscovy succeeded in expanding: It moved into Siberia, then retook Ukraine in 1564. Sweden had pushed into the Baltic region, taking Estonia and Latvia, but after the Great Northern War of 1700 to 1721, Russia folded both those areas into its realm. Peter the Great reorganized the government, proclaimed himself emperor and renamed his empire Russia. The Rzeczpospolita fell in 1795 and Lithuania, too, was swallowed up by Russia. About the same time, Russia also gained Moldova, which had been controlled by the Ottomans. Russia continued to expand in the 1800s, taking Finland in 1809 and the rest of Poland in 1815. At that point, its empire covered one-sixth of the world’s land.

As in the neighboring Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, 19th-century imperial Russia was still entrenched in feudalism. Serfdom in Russia began in 1649; in Polish-Lithuanian lands, it hardened during the Rzeczpospolita. Feudalism endured longer here, with Russia not emancipating its serfs until 1861. The difficult transition from a medieval, agrarian society to a more modern, industrial one helped to spur immigration to America. “This led to the disruption of traditional agriculture and the demise of the small-scale family economy,” says Ira A, Glazier, editor of Migration from the Russian Empire. Overpopulation, disease and poverty led peasants to flee; “Russification” policies and forced conscription also pushed many to America’s shores.

Jewish people in the Russian Empire had other reasons to go to America. Beginning in 1835, the government required Jews to live in only the “Pale of Settlement” — provinces on the western fringes of the empire, in what’s now Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine. (The government also mandated vital-record-keeping.) A series of pogroms from the 1880s to 1914 fueled massive Jewish emigration.

The empire’s social problems finally boiled into revolutions in 1905 and 1917. In the midst of World War I, Czar Nicholas abdicated, ending the three-century Romanov dynasty. Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks seized power from the provisional government and attempted to create the first soviet (workers’ council) state. The ensuing civil war of 1917 to 1921 pitted the Bolshevik “reds” against the anti-Bolshevik “whites.” Lenin and the reds won, and Russia became the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922, setting the stage for the Cold War era.

Making waves

Small surges of Russian and Baltic immigrants came to America after the Bolshevik revolution and World War II, including waves of Jews who fled Europe during the Holocaust. But by the Soviet era, the largest numbers of immigrants from this region had already arrived — in part because of tougher US immigration laws that limited entry by Eastern Europeans.

The earliest Russian immigrants were fur traders and hunters who settled in Alaska and California. This exploration grew out of the empire’s eastward expansion through Siberia. Bering discovered the strait that bears his name in 1727 and landed on the Aleutian Islands in 1741. Beginning with Kodiak Island in 1784, Russian traders established dozens of Alaskan settlements. When Russia sold Alaska to the United States in 1867 — -at the bargain price of $7.2 million — half the settlers returned; others moved to California. In the early 20th century, the West Coast again attracted Russians, primarily religious sects such as the Molokans, Dukhohors and Old Believers.

The largest influx from Russia, however, came during the “great migration” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. More than 2.3 million immigrants from czarist Russia entered the United States between 1871 and 1910. Most came from the western areas of the empire — places outside Russia’s current borders — including nearly three-quarters of a million Jews from the Pale.

This great migration brought an estimated 100,000 Belarusians and 250,000 Ukrainians. Although the Russian-controlled provinces of Volhynia and Kiev supplied significant numbers of Ukrainian immigrants, the majority — 85 percent — came from Galicia and Bukovina, which were then controlled by Austria-Hungary. From 1860 to 1914, 300,000 Lithuanians arrived, primarily from the provinces of Kaunas, Suvalkija and Vilnius. Fewer immigrants came from the other modern Baltic countries: 5,000 Latvians entered from 1905 to 1913, and an estimated 70,000 Estonians were here by 1920.

These immigrants usually left from North Sea ports, especially Hamburg and Bremen in Germany. Although Bremen’s pre-World War I emigration records were destroyed, Hamburg’s records still exist. You can borrow microfilmed indexes and lists from the Family History Library (FHL) — check the catalog at <www.familysearch.org> — or access digitized copies through the Hamburg State Archive’s fee-based database at <www.hamburg.de/fhh/behoerden/staatsarchiv/link_to_your_roots/English>, which currently covers 1890 to 1900.

New York was the immigrants’ main port of entry. The biggest waves came during the heyday of Ellis Island; you can search those records online at <www.ellisisland.org>. Before 1892, New York arrivals were processed at Castle Garden. Check Ira A. Glazier’s Migration from the Russian Empire series for immigrants processed at both stations from 1875 to 1910. And don’t overlook other Northeast ports — not everyone came through New York. Latvians favored Boston, for example. You can get microfilmed passenger lists from these ports through the National Archives <www.archives.gov> and your local Family History Center branch of the FHL.

Speaking their language

Finding your immigrant ancestor, of course, is the key to extending your family tree to Europe. To have any hope of doing that, you’ll need two clues: your immigrant’s original name and hometown. These facts are crucial because they’re the only way to find and identify your family in European records — but they can be tricky to determine because of foreign-language hurdles.

• Names: Many immigrants “Americanized” their names once they arrived in the United States. For example, they might have adopted the English equivalent, chosen a similar-sounding name or made the spelling more American. (Despite popular lore, Ellis Island immigration officials did not change people’s names — you can learn more about this myth at <www.ins.usdoj.gov/graphics/aboutins/history/artides/llameEssay.html>.) For ancestors from the former Soviet Union or Russian Empire, new names were inevitable — Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians would at least have to transliterate their names from the Cyrillic to the Roman alphabet.

Keep in mind that Slavic- and Baltic-surname spellings often vary in grammatical context. Different suffixes denote gender and marital status. In Lithuanian, for instance, unmarried women’s names end in -aite, -yte, -ute or -te, while married women’s surnames end in -iene. Russian female surnames end in –a. You’ll need to pare down names to their “root” forms to track your ancestors.

Be aware of naming customs, too. In following the Paper Trail: A Multilingual Translation Guide (Avotaynu), Jonathan D. Shea and William F. Hoffman advise learning the Russian tradition. “Generally, Moscow has forced even non-Russians under its control to comply with Russian customs regarding names,” they explain. The system works like this: Each person has a given name, patronymic and surname. The patronymic usually ends in -ovich for men or -ovna for women.

Orthodox and Catholic families frequently named children for saints, selecting one whose feast day was close to the child’s birthday. Jewish families named children after close deceased relatives. Jews in the Russian Empire didn’t adopt surnames until the government began requiring their use in the early 19th century.

• Towns: As you search US sources for the place your ancestors came from, you’ll need a basic understanding of foreign geographical terms. Otherwise, you’ll have trouble separating specific place names from more general descriptions. If you know that gubernia is Russian for province, you won’t assume that Grandma came from the city Minsk if her naturalization papers give her birthplace as Minsk Gubernia. A list of terms for historical and present-day administrative districts is at <www.rtrfoundation.org/admindist.html>.

You should also become familiar with different names for your family’s province and town — many places have names in multiple languages. Take L’viv, Ukraine: It’s been known as Lvov in Russian, Lwów in Polish, Lvuv in Yiddish and Lemburg in German. The city was the historical center of Galicia (Halychyna in Ukrainian), an area now split between Poland and Ukraine. Gazetteers will help you unpuzzle these name switches and locate defunct and tiny towns. Gary Mokotoff and Sallyann Amdur Sack’s Where Once We Walked (Avotaynu) is especially valuable for Jewish researchers because it identifies pre-Holocaust towns. Check the FHL catalog at <www.familysearch.org> for gazetteers that cover your ancestral country.

Ethnic organizations also may have resources and researchers for you to consult. The Balzekas Museum for Lithuanian Culture, for example, assists in town research. And don’t forget online resources, such as the Jewish-Gen Shtetl Seeker at <www.jewishgen.org/ShtetlSeeker>. This place-name database is useful for all Eastern European researchers.

Once you’ve identified the name and town, you’ll face a dizzying array of potential languages in European documents. Records from the USSR or Russian Empire are usually in Russian. Depending on the place and time, records may be in Polish, Hungarian, Romanian, Yiddish, German or Latin in addition to or in place of your ancestors’ native language.

Don’t panic — not even the most dedicated genealogist will master all those tongues. “You don’t need to speak the language at all,” assures Weiner. “You can work with a translator.” Ethnic and professional genealogy groups can recommend translators, or consult the online directories for the Federation of East European Family History Societies <feefhs.org/frg/frg-pt.html> and the Association of Professional Genealogists <www.apgen.org/directory>.

So stick to learning basics such as foreign alphabets and key genealogical terms, and be able to recognize names and places. The Routes to Roots Foundation Web site, which Weiner created and maintains, has a key to Russian genealogical terms and downloadable alphabet charts for nine languages at <www.rtrfoundation.org/archdta.html>. Following the Paper Trail offers genealogical word lists for Russian, Lithuanian, Polish, German and Latin, plus sample records and their translations.

Recording your past

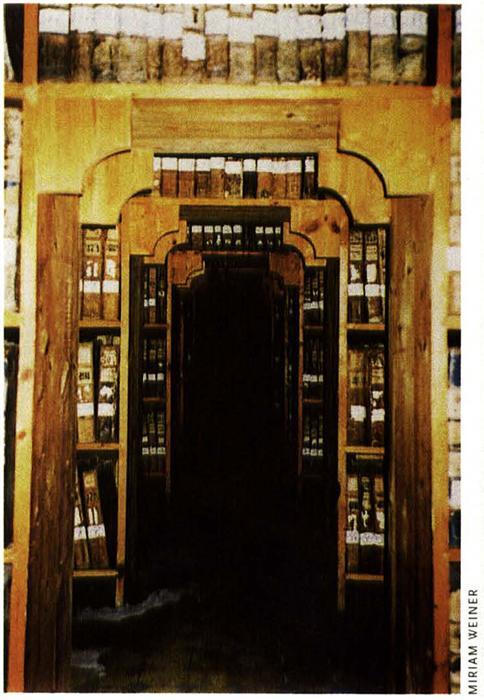

Perhaps the greatest challenge of roots research in the former Soviet Union is limited access to records. Weiner has been conducting archive research there since 1991 and warns the work isn’t easy: Records aren’t fully microfilmed, organized or digitized as they are here, and finding aids are scarce. “It’s very often difficult to determine what records exist for a specific town,” she says. Worse, some records have been destroyed, which means your family tree might be stunted by gaps in the archives’ collections.

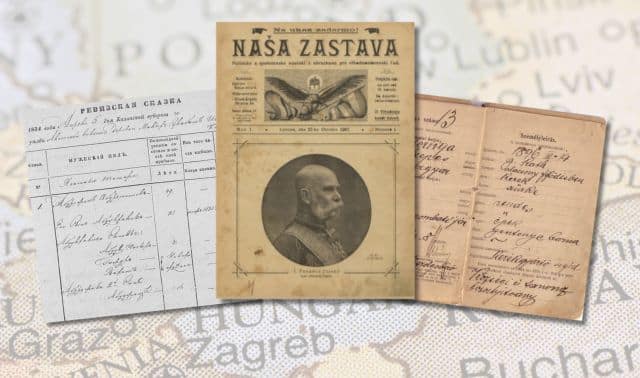

Record-keeping in the Russian Empire mostly resembled the practices elsewhere in Europe. Vital records were the purview of the church before the government stepped in. Older parish registers are usually held by an archive, while more recent ones (within the last 75 years) are in civil registration offices, says Kahlile Mehr, an FHL collection development specialist. The government took 10 poll-tax censuses, referred to as revision lists (revizskie skazki), between 1719 and 1859. They’re organized by place, then by social class, such as nobility (dvorianstvo), peasants (krest’iane), Cossacks (kazaki) and Jews (yevreyski). Surviving revision lists are in regional and historical archives, as are remaining copies of the 1897 census of the entire empire.

Some records have been microfilmed by the FHL. Its Estonian records represent the most complete film collection for any Eastern European country. But that’s the exception — the library has several thousand church books for Belarus, Lithuania and Moldova, close to 25,000 for Ukraine and 45,000 for fewer than a dozen Russian provinces, plus assorted tax, census and other records. To see exactly which records are available, try a place search of the FHL catalog. You’ll also find a good rundown of available Jewish records at <www.jewishgen.org/infofiles/eefaq.html>.

Another option is to write to the archives — success on this front is increasing. Some national archives, including Belarus and Ukraine, have even put instructions and fees on their Web sites. But responses from the archives vary. Weiner says your level of success will depend on the archives’ location, facilities, equipment and communications. You also have to provide detailed information about the searches you want and send the fees (nonrefundable, of course) in advance. Your best bet, when possible, is to determine whether the records you want exist before you request archive research. You’ll find some inventories on archives’ Web sites and through the FHL. Jewish researchers have an excellent resource in the Routes to Roots Foundation’s Eastern European Archival Database <www.rtrfoundation.org/archdtal.html>: It catalogs surviving archival records in Belarus, Lithuania, Poland, Moldova and Ukraine.

When microfilmed records are unavailable and the archives’ response is dubious, your wisest choice is probably to hire a professional. But Weiner urges caution. “It’s like the Wild West with people setting up research services,” she says. Some researchers are seizing a moneymaking opportunity, peddling services to foreigners regardless of the researchers’ experience or qualifications. You should always get references from previous clients and a written agreement that outlines costs, the method of payment, a time frame for completing the research and the format of the researcher’s report.

The final option, now that the doors to your ancestral homeland are finally open, is traveling there to research yourself. If that’s your plan, however, Weiner warns that you might not get the results you hope for. The archives’ staff likely won’t speak English, and they don’t work at the speed we’re accustomed to. You might travel those thousands of miles only to be told that the archives will send you an answer later.

But if you do decide to go, preparation is key. Contact the archives well in advance to find out the facility’s hours, policies and holdings. Bring a translator with you — it’s tedious work, and you’ll want to accomplish as much as possible in the time you have.

Still, these challenges are little cause for disappointment or discouragement. Today’s maybe is better than yesterday’s nyet. “Who ever dreamed we could even do this?” says Weiner. Indeed, many Americans with roots in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania could barely imagine these new family history possibilities, or the chance to walk in their ancestors’ footsteps. The iron curtain is history — and you can finally reclaim your family’s past for the future.

ADVERTISEMENT