Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Jump to:

The birth of birth records

Obtaining a birth record in 4 steps

Privacy-protected birth records

Birth record substitutes

Other birthdate resources

Related Reads

Whatever your heritage, your ancestors had at least three things in common: They were born, they produced descendants and they died. Surprisingly, it’s that first and most basic life event — birth — that can be the most challenging for genealogists to document.

Births have historically been less bureaucratic than marriages, which typically require church and state sanction (and therefore paperwork), and deaths, which usually generate cemetery and probate records. In our ancestors’ day, most births took place at home, so not even hospital records recorded those blessed events. The church’s involvement begins with baptism, whose records may provide valuable clues but necessarily follow births by at least several days (and sometimes, years). Moreover, your ancestors’ births simply lie further back in the mists of history than their other life events. So if their births were recorded at all, the official documents are likely sparser, harder to locate or lost to the ubiquitous courthouse fire. More-recent birth records may be off-limits because of privacy restrictions.

This doesn’t mean you should despair of finding your ancestors’ birth records. To the contrary: If you know where to look, you often can find evidence of births that happened before states required certificates, and get substitute sources for births that escaped official notice. So stop laboring fruitlessly and locate those documents with our advice.

The birth of birth records

The information in a birth record varies by geography and time period. At a minimum, it should give the child’s full name, gender, birth date and place, and the parents’ names. Sometimes you’ll get other key facts, such as the parents’ birthplaces. Keep in mind the government-issued birth certificates we take for granted today are a recent phenomenon that began during the late 1800s to early 1900s. Before that, courthouse clerks sometimes recorded births in a simple register. In large cities, local health departments may have tracked vital events — these records, though incomplete, exist for Baltimore (from 1875), Boston (from 1639), New Orleans (from 1790), New York City (from 1847) and Philadelphia (from 1860). They’re available on microfilm from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL). You can rent FHL film via a local branch Family History Center — use the Web site to find one near you.

You may have ancestors whose towns got a head start on vital-record-keeping. New England town clerks began keeping birth registers in Colonial days, as early as the 1630s. Bolton, Conn., for example, kept vital records starting in 1704; you can access these on FHL microfilm, or through the New England Historic Genealogical Society‘s subscription databases. But Connecticut was among the last of the New England states to adopt state-level vital-record-keeping, which it finally did in 1897. Vermont was even slower, waiting until 1919 to begin.

Other regions were less farsighted, at least from the genealogist’s viewpoint, than those persnickety Yankees. The Middle Atlantic states required birth registration between 1878 and 1915. (The District of Columbia is, of course, a special case. Registration began in 1874, though most births went unrecorded until 1915. Its Vital Records Division of the Department of Human Services keeps the records.) Most Southern states enacted laws requiring birth registration between 1899 and 1919, although Virginia counties had been recording births since 1853 (with a gap from 1896 to 1912). In Midwestern states, counties often kept records as early as the 1860s, but state requirements weren’t enacted until 1880 to 1920. Likewise, Western states typically began birth records with the creation of each county, while statewide vital records didn’t start until the 20th century. Hawaiian birth records date back even before the islands became a US territory, to the 1850s.

Obtaining a birth record in 4 steps

The basic steps to obtaining an official birth record involve figuring out the right office to contact and making a request. Here’s an overview of the process:

Step 1: Ironically, tracking down a birth certificate may require already knowing most of the information you hope to find when you get your hands on it. (It’s still worth the search as a primary-source confirmation of what you think you know about an ancestor.) Besides your ancestor’s name, you’ll need at least an educated guess about place and date of birth. If you don’t know, try looking in family letters and other papers, your clan’s Bible, newspaper birth announcements and obituaries, church records and military records. You even can tap sources such as the pedigree files researchers have submitted to database sites.

Step 2: Next, investigate when your ancestor’s hometown began keeping birth records by consulting The Family Tree Resource Book for Genealogists, Red Book: American State, County and Town Resources or The Handybook for Genealogists (see page 25 for publishers and prices). As we’ve noted, this date isn’t necessarily the same year statewide record-keeping began. In most places in the United States, you’ll look for the date your ancestor’s county started keeping records. For New England ancestors, look at towns; many large Northeastern cities kept their own vital records, too. You also may find help on the county’s USGenWeb site or the county government’s website.

You’ll also need to make sure you’ve got the right place on today’s map. County borders and names changed as the nation grew: A relative born in 1902 in the town now called Allendale County, SC, would have actually started life in either Barnwell or Hampton counties, from which Allendale was formed in 1919. If you learn official records don’t cover your ancestor’s birth, follow the advice in the box below.

Step 3: Now it’s time to figure out where to look for the document. Copies of birth records may be at both the state and county levels, or the location may depend on the date — some states transfer old records to a state archive, vital-records office or even a health department. In Illinois, for example, birth records since January 1916 are at the state Division of Vital Records, part of the Department of Public Health. Earlier records remain in the individual counties or at the Illinois Regional Archives Depository; you can check the holdings for your ancestor’s county.

The reference books mentioned in step 2 can help you learn locations of records; alternatively, consult the National Center for Health Statistics’ Where to Write for Vital Records or VitalRec. Links on these sites usually take you to state government Web sites for more-detailed information and instructions.

Step 4: Closely follow the repository’s instructions for requesting a birth record. You may have to complete a form with enough information for the office to find your ancestor’s record: full name, sex, date and place of birth, and parents’ names (if known). You’ll typically pay a fee ($15 in Illinois, for example) and you might have to include a photocopy of your driver’s license. Be sure to mention you want the record for genealogical purposes, and describe your relationship to the person whose record it is. Another option is to order records online using a service such as VitalChek, though these sites’ fees are higher than what state agencies charge. If all goes well, you’ll have a copy your ancestor’s birth certificate in about four to six weeks.

Privacy-protected birth records

In our era of identity theft and privacy paranoia, unfortunately, your quest may hit a snag: Many states protect birth records behind a privacy “curtain” for 75 or even 100 years after the birth. Some require you to prove your relationship to the individual and/or provide evidence the person is deceased (such as a copy of a death certificate). Some states limit access to immediate family members.

Again, regulations vary. Continuing with our Illinois example, only the person whose birth is recorded, a parent or a legal guardian can obtain a certified copy of a birth certificate. But you can get an uncertified copy for genealogical purposes if the person’s birth occurred more than 75 years ago or the person has died (in which case you need to complete a special application form and show proof of death).

Other states don’t make such genealogical exceptions. Georgia, for instance, limits access to birth certificates strictly to the person named and that person’s parents, legal guardian, grandparents, spouse, sibling or child. Nope, you can’t even get your own grandparents’ birth certificates, even if Grandpa and Grandma are dead. The good news is Georgia researchers aren’t missing much, since that state’s birth records date only from 1919 anyway.

Where can you turn if your ancestor’s state completely shutters its birth records — or if your ancestor was born before such records existed? The first option is to look for a delayed birth certificate. Those born before the advent of birth certificates often needed such documentation to get Social Security benefits, passports or pensions. A person could apply for a delayed birth certificate by proving his age with other documents, such as baptismal certificates, affidavits signed by relatives, voter registration records, censuses, school records, naturalization papers, even family Bibles and insurance papers.

Delayed birth certificates may not be subject to the same stringent rules as regular birth certificates, and you might find them using more-familiar genealogical channels. For instance, South Carolina restricts birth certificates to the person named, that person’s parents or legal guardian and — if the person is dead — immediate family members who supply “an original certified copy (no photocopies) of the registrant’s death record,” adding curtly, “There are no exceptions.” But the Family History Library has 42 microfilm rolls of delayed birth certificates from South Carolina covering 1766 to 1900. You can do a keyword search of the FHL catalog for delayed birth certificates to see if your ancestor’s birthplace and time period is included among the 564 such record collections.

Birth record substitutes

What can you do if you’re still stymied in your quest for proof of your ancestor’s birth? While not as satisfying or as evidentially solid as a birth certificate, other records may nonetheless exist.

Indexes: Ancestry.com ($199 a year) has searchable birth indexes for states including California (1905 to 1995), North Carolina (1800 to 2000), Kentucky (1911 to 1999), Massachusetts (varies by town), Minnesota (1935 to 2002), Texas (1903 to 1997), Washington (1907 to 1919) and various Virginia and Indiana counties. You can search USGenWeb and RootsWeb for transcriptions of various local birth registers.

Some states have put birth indexes on the web. Records from several Colorado counties are available online. The Missouri Birth and Death Records Database is an abstract of pre-1909 birth, stillbirth and death records available on microfilm at the state archives. A wide range of records, including 13,000 Portland births between 1881 and 1902, are cataloged in the Oregon Historical Records Index.

You can search pre-1907 vital records at the Wisconsin Historical Society‘s site and then order hard copies of your finds. The Minnesota Historical Society‘s 1900-to-1916 birth index works similarly. Search South Dakota births from more than 100 years ago at the state’s Department of Health site. Arizona Genealogy Birth and Death Certificates lets you search indexes of births from 1887 to 1929.

For more general information, check out Cyndi’s List. Don’t overlook the possibility of microfilmed and printed indexes, either. To find relevant resources, do a place search of the FHL catalog for your family’s town, county or state and look under the heading Vital Records — Indexes.

Bibles and baptisms: These familiar genealogical resources can fill in for absent birth certificates. If you have ancestors in Lee County, Ga., for instance, you’d be stymied not only by Georgia’s privacy restrictions and late start on statewide record-keeping, but also by an 1858 courthouse fire. But you might get lucky and find a forebear in the family Bible of Britton Gainer Smith and Sarah Livingston Smith, part of Lee County’s USGenWeb site: Little Johnny J. Smith was born “the 27th October A.D. 1846.” USGenWeb sites have many such Bible transcriptions — just choose a state from the home page, then click on a county — and you can find links to other collections at Cyndi’s List.

Baptism records can take you far back in time — long before birth certificates began — but of course they don’t necessarily tell you an ancestor’s birth date. Still, you can get most of the other information you’d look for on a birth record, including the names of the baby’s parents. Take New Kent County, Va., where birth records don’t begin until 1865: If your ancestor happened to be a member of St. Peter’s church in the southern part of the county, you could try the parish registers. They cover 1680 to 1787 and include births as well as baptisms, such as “David son of Tho. Smith Gent. by Mary his wife born the 1st March and baptised the 3d March, 1698-9.”

Newspapers: Newspaper birth announcements — until the 20th century, less common than marriage notices and obituaries — are a potential source for more-recent ancestors. Purchase a Newspapers.com membership (either as part of an Ancestry All Access subscription, or by itself), or see if your local library offers a free newspaper index such as Access World News. Your ancestral county library or genealogical society may have published a local newspaper index — check the Web site or make a phone call. Many papers are on microfilm at libraries and historical societies, but most aren’t indexed, so be prepared with a guess as to your ancestor’s birth date.

Digging up your ancestors’ birth records may indeed turn out to be one of your biggest genealogical challenges. But if you use the hints and how-tos here, you’ll soon have joyful news to share about new branches of your family tree.

Other birthdate resources

So your efforts to find your ancestor’s birth records aren’t bearing any fruit? You still can get your hands on the information in these records:

- 1900 US census (provides the birth month and year)

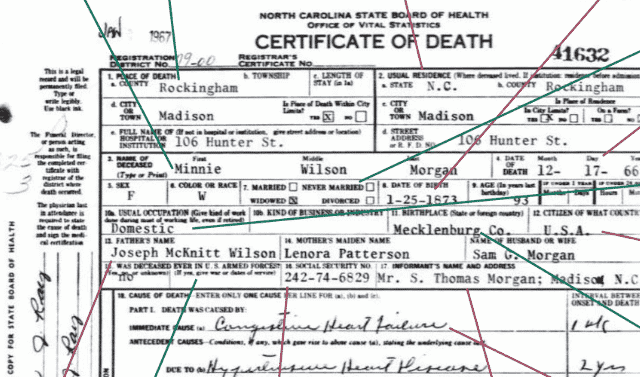

- death certificates

- family Bibles

- letters and diaries

- military pension and service files

- naturalization records (sometimes)

- passports

- school, hospital and other institutional records

- Social Security application

- tombstones (beware — inscriptions are sometimes incorrect)

A version of this article appeared in the December 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT