Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Your ancestors’ naturalization records hold a boatload of information for you: Depending when your immigrant ancestors sought citizenship, naturalization records can give you the precise date and port of arrival, the name of the ship, the port of departure, and the birth date and place. Fortunately, you don’t have to be a genius to figure out how to get your ancestors’ naturalization papers. Below is our four-part formula for tracking those documents.

1. Learn immigration history

Between 1776 and 1790, each state had its own procedures for aliens to become citizens. After 1790, when Congress passed the first federal naturalization law, a series of acts changed restrictions and requirements over the centuries.

In 1790, the applicant for citizenship had to be a free white male, age 21 or older, who’d lived in the United States for two years and in the state in which he applied for one year. The applicant could apply in any court of public record — federal, state or local. His children would automatically become citizens, too.

A 1795 law created a two-step process to gain US citizenship. First, the applicant filed a declaration of intention, then, after a minimum of three years, the alien could petition for naturalization (learn more in tip 2). This law also extended eligibility to free white females 21 and older, and the US residency requirement increased to five years. In 1798, the government lengthened the residency requirement to 14 years, but in 1802 scaled it back to five years, where it’s remained since.

Legislation in 1824 shortened to two years the waiting period between declaring intent and petitioning for naturalization. This law also allowed “minor naturalization” — that is, one-step naturalization for applicants who were under age 18 when they immigrated and who’d resided in the US for three years before turning 21 and petitioning for citizenship.

In addition, immigration laws often set restrictions based on ethnicity and nationality — in particular, for non-Western European peoples. The 14th Amendment, of course, had granted citizenship to former slaves upon its ratification in 1868. The subsequent Naturalization Act of 1870 allowed others of African descent (including African-born people and Caribbean blacks) to pursue citizenship.

Asians couldn’t become citizens from 1882 until 1943. The government classified Indians and Filipinos separately from other Asians, but their status wasn’t much better — they were banned from citizenship until 1946, except Indians for a short period (1910 to 1923). A 1924 act granted full citizenship to American Indians.

Between 1855 and 1922, alien wives had derivative citizenship: They automatically became citizens when their husbands did or when they married American citizens. Conversely, Congress declared in 1907 that if an American woman married an alien, she lost her citizenship and took on her husband’s nationality. She wasn’t eligible for US citizenship again unless her husband was naturalized. Beginning in 1922, women could obtain citizenship independently and keep it even if they married non-Americans.

The most important date for family historians to know is 1906: That year marked the creation of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS; now known as US Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS. From 1906 until 1990, all courts across the country had to forward copies of naturalizations to INS — effectively centralizing the records. In 1990, jurisdiction for naturalizations moved to the attorney general’s office.

Want to learn more about US naturalization laws? Consult American Naturalization Processes and Procedures, 1790-1985 by John J. Newman (Heritage Quest) and They Became Americans: Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins by Loretto Dennis Szucs (Ancestry). If your ancestors landed in Canada, try The Canadian Genealogical Sourcebook by Ryan Taylor (Canadian Library Association).

2. Follow the path to citizenship

So with some exceptions, your immigrant ancestors probably followed the two-step naturalization formula: declaration of intention (first papers) + petition for naturalization (second or final papers) = citizenship. As you’ll see from this synopsis, the genealogical details produced during the process can add up, especially for later arrivals.

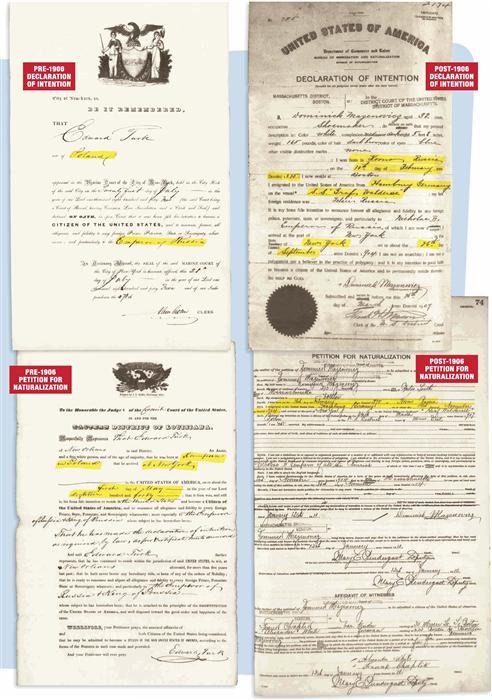

First papers: In this document, an alien renounced his allegiance to his homeland and declared his intention to become a US citizen. The immigrant could make his declaration as soon as he stepped off the boat. Pre-1906 declarations usually contain the immigrant’s name, country of birth or allegiance (for example, an Ireland-born immigrant would’ve renounced allegiance to the British Crown), application date, and the applicant’s signature. Few of these early records give more than the country of origin or the date and port of arrival. Post-1906 declarations of intention also included the applicant’s name, age, occupation, personal description, birth date and place, citizenship, current address, last foreign address, vessel and port of embarkation, US port and date of arrival, date of application and signature.

Second papers: In the naturalization petition, an immigrant who’d filed his first papers and met residency requirements made a formal application for citizenship. Starting in 1906, second papers included the petitioner’s name, residence, occupation, birth date and place, citizenship and personal description; the date he emigrated; the arrival and departure ports; marital status (with wife’s name and date of birth, if married); names, dates and places of birth and residence of the applicant’s children; the date when US residence commenced; his length of residence in the state; name changes; and his signature. After 1929, the declaration and final certificate included photos.

Despite the requirement to do so, some courts didn’t make applicants file petitions for naturalization prior to 1903. The Justice Department created a special form that year, but not all courts used it. As a result, 19th-century records contain some or all of the following data: the applicant’s name, country of birth, date of application, signature, date and port of arrival, occupation, residence, age, birthplace and birth date.

Members of the military: Various laws have allowed members of the military or veterans to expedite the naturalization process. An 1862 law allowed honorably discharged Army veterans of any war to petition for naturalization after one year of residence in the United States, without filing a declaration of intent. This privilege was extended to honorably discharged five-year veterans of the Navy or Marine Corps in 1894. May 9, 1918, Congress passed a law to allow aliens who’d been in the Armed Forces for at least three years to file a petition for naturalization without proof of the five-year residency requirement, and that any alien who’d been in the service during World War I could skip the declaration of intention.

The Naturalization Act of 1906 mandated a 90-day waiting period between filing the petition and the hearing when citizenship was granted or denied. No naturalization hearings occurred in the 30 days before a general election in the court’s jurisdiction. The new citizen received a certificate bearing the seal of the naturalizing court. Your family might’ve passed down this document — check with relatives.

3. Locate the records

Now that you’re familiar with the naturalization formula, you’re ready to hunt down your forebears’ records. Begin at the Family Search Wiki with United States Naturalization and Citizenship Online Genealogy Records, which has links organized by state. Remember, before 1906, your ancestor could go to any courthouse to become a citizen — he could even begin the process in one court and finish it another. Check municipal, county, state and federal courthouses where the immigrant arrived or settled.

City, county, regional or state archives also could hold your ancestor’s records. Naturalizations made in municipal courts might be in the town halls or city archives of major cities such as Baltimore, Chicago and St. Louis.

Although courts had to file copies of naturalizations with INS after 1906, USCIS isn’t the fist place to look for your ancestor’s records. Begin with the FHL, doing the same type of search as for pre-1906 records. Fee-based websites sites Fold3 and Ancestry.com have collections of naturalization records worth searching, as well.

Then try the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). NARA’s regional facilities hold naturalizations from federal courts; you can learn more about each branch’s holdings at archives.gov/locations.

As a last resort, send a Freedom of Information/Privacy Act request using Form G-639 to the USCIS National Record Center. If the person is still living, you’ll need to provide notarized permission to obtain the records. If your ancestor was born less than 100 years ago, you’ll need to provide proof of death. The first 100 pages of the file (if only!) will be copied for free. After you send your request, forget about it. Seriously — it can take several months to get a response.

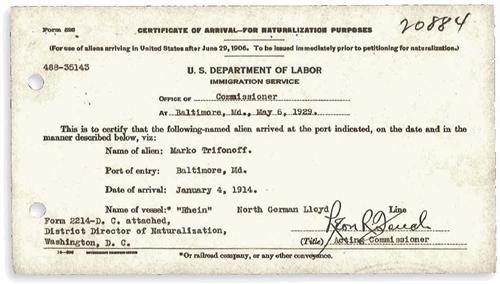

Besides a declaration and petition, your ancestor could’ve generated a few other types of records during the naturalization process. Between 1906 and the early 1940s, INS created certificates of arrival: When an immigrant applied for citizenship, officials would check the ship’s manifest to verify legal admission. If INS was able to find the arrival record, the agency would then issue the certificate and send it to the court where the alien applied for citizenship. If your ancestor has a certificate of arrival, it should be on file with the naturalization record. It will list the port of entry, the date and the name of the ship.

Although largely unindexed and arranged by filing date, surviving naturalization certificate stub books are another resource. Most courts didn’t keep a copy of the naturalization certificate given to the new citizen, but they might’ve retained the stubs attached to the certificates that were bound in volumes. These records varied in content over time and from one court to another; they may contain the date the alien declared his intention to become a citizen, his age, and the names and ages of his wife and children. Look for stub books in courts that handled naturalizations, as well as archives and historical societies.

4. Consider other outcomes

Members of some ethnic groups, such as Italians, Poles and Greeks, were slow to become naturalized, if at all. Others, including Asians, weren’t even allowed to become citizens until relatively recently. Typically, men who were birds of passage — going between their homeland and America several times before settling here — didn’t rush to become citizens. Often, their goal wasn’t to stay in America permanently; it was to earn money and return to their homeland to buy land. Keep that in mind if you can’t find a naturalization record for your ancestor, or you find one dated years after he arrived.

As with any bureaucratic process, people found ways to avoid citizenship. For example, a person might obtain several copies of his declaration, then sell them at election time so aliens could vote. (This happened particularly in large Eastern cities in the 1880s.) Also, more aliens applied at the county and state levels than at federal courts because the fee was usually lower, standards may not have been as stringent, and it was probably closer to home.

If you’re still having trouble finding your ancestor’s naturalization record, check these records for clues:

Voter registrations: After 1906, citizenship was required for an immigrant to vote. Generally, voter records are at the county or city level, but some states kept voter lists in the secretary of state’s office. Many voter records give naturalization details. Voter registration records may exist only for the past five to seven years, but some counties retain earlier records — or donate them to another repository.

Homestead applications: Immigrants had to at least file a declaration of intention before they could apply for land under the Homestead Act of 1862. To secure the patent to the homestead at the end of the five-year term, the alien had to have acquired US citizenship. You’ll find copies of the declaration and petition in the homestead files of foreign-born homesteaders. You can get these files from NARA, the appropriate state’s Bureau of Land Management office <www.blm.gov> or the county courthouse.

Military records: Starting with the Civil War, aliens who served in the US military and were honorably discharged could apply for citizenship without filing a declaration of intention and without the usual residency requirement. Citizenship wasn’t automatic, however. The military service record probably won’t contain the naturalization record, but if the veteran applied for benefits, it may be included there. Check Ancestry.com’s digitized WWI draft records, which give naturalization information, and Fold3’s Index to Naturalizations of World War I Soldiers, 1918.

Censuses: Beginning in 1900, enumerators recorded whether immigrants were naturalized. Some state censuses, such as New York’s in the early 1900s, also give the place of naturalization.

And if all else fails, you can always look for an FBI dossier.

A version of this article appeared in the May 2008 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to Amazon and affiliated websites.

ADVERTISEMENT