Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

My mom’s family has a long-standing tradition of surprise babies that appear just when my relatives think they’re finished procreating. Consequently, ages vary quite a bit within generations. When an aunt got into genealogy, she told me the boy I grew up knowing as a garden-variety cousin actually is my first cousin once removed. He’s the son of my grandma’s youngest brother — who’s my great-uncle, even though he’s my mom’s age.

Wild!

But that’s nothing. Now that I work for a genealogy magazine, I’ve learned the endless possibilities of cousinhood. Your number of grandparents doubles with each generation, so count back 10 and that’s 2,046 total ancestors. Which means the cousin potential is exponential — you could have millions of them. Fourth cousins, second cousins three times removed, tenth cousins twice removed … I could go on. And with e-mail lists and online message boards that connect you to new cousins every day, you’d better start figuring out exactly how you’re related.

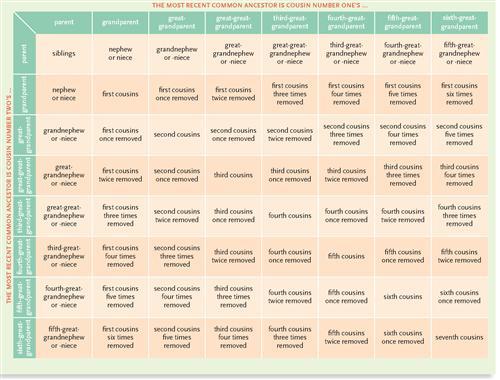

Just about any other blood relative who isn’t your sibling, ancestor, aunt or uncle is your cousin. To determine your degree of cousinhood — first, second, third, fourth — you need to identify the ancestor you share with your cousin, and how many generations between each of you and that ancestor.

Your first cousin (sometimes called a full cousin, but usually just a cousin) is the child of your aunt or uncle. The most recent ancestor you and your first cousin share is your grandparent. Your second cousins are the children of your parents’ first cousins. Take a look at your family tree, and you’ll see that you and your second cousins share great-grandparents. For third cousins, great-great-grandparents are the most recent common ancestor. You get the picture.

Time for a pop quiz: What’s the relationship between your granddaughter and your sister’s grandson? And the answer is … second cousins. The kids’ most recent common ancestor is their great-grandparent (your parent).

Remove yourself

“I aced that one,” you say, “but what about a removed cousin? Or a fourth cousin three times removed? What does that mean?”

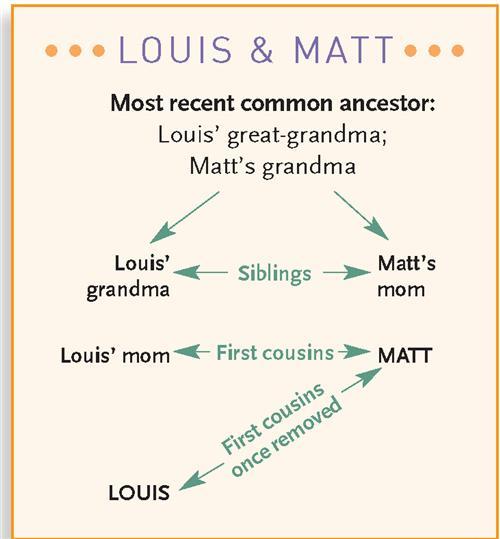

Take my nephew, Louis. He and my aunt’s 6-year-old, Matt, share my maternal grandmother as their most recent common ancestor (see the illustration). My grandma is Matt’s grandmother, too, but she’s Louis’ great-grandmother. (My sister has taken pains to explain to him why this grandma is great and his other grandma is just ordinary. We think he gets it now.) Matt’s just one generation away from their common ancestor, so he and Louis are first cousins. But Louis is two generations away from that common ancestor — which makes Louis and Matt first cousins once removed.

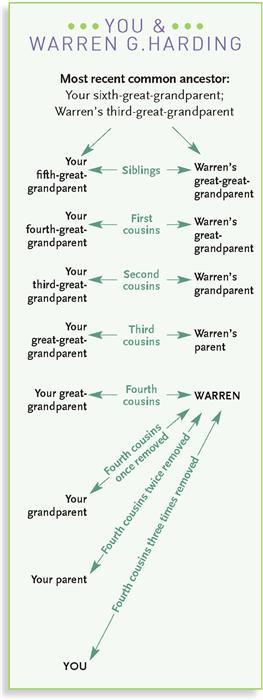

You can be distantly related to deceased individuals through removes, too. For example, say you’re fourth cousins three times removed with Warren G. Harding. (The mind-boggling number of cousins you have means there’s bound to be someone famous in your .) That would mean your sixth-great-grandparents are Harding’s third-great-grandparents. See the the box for an illustration of this relationship.

Anthropologists call the process of figuring out cousin relationships “collateral degree calculation.” (Don’t worry, we promise not to spring that term on you again.) Multiple removes and degrees of cousinhood can get complicated, but you don’t have to be a scientist to get it right — the chart above will help straighten out your kin confusion. Just follow the instructions for using it.

Despite how it sounds, a kissing cousin isn’t a cousin you marry. Rather, it’s any distant relative you know well enough to kiss hello at family gatherings. Now we’re begging the question: How close a cousin is too close to wed? States have different laws (and we’ve heard all the jokes, so just stop right now) governing consanguineous marriages. It’s best to ask a lawyer about statutes for the state in question.

Relatively Helpful

1. Identify the most recent common ancestor of the two individuals with the unknown relationship.

2. Determine the common ancestor’s relationship to each person (for example, grandparent or great-grandparent).

3. In the topmost row of the chart, find the common ancestor’s relationship to cousin number one. In the far-left column, find the common ancestor’s relationship to cousin number two.

4. Trace the the row and column from step 3. The square where they meet shows the two individuals’ relationship.

All in the Family

Think you have unusual relatives?

Genealogy makes strange bedfellows — just consider these odd couples:

- Elvis Presley and Jimmy Carter: sixth cousins once removed

- George W. Bush and John Kerry: ninth cousins twice removed

- George Washington and William Holden: third cousins nine times removed

- Lizzie Borden and Elizabeth Montgomery: sixth cousins once removed

- Madonna and Celine Dion:10th cousins once removed

From the May 2005 Beginner’s Guide to Genealogy

ADVERTISEMENT