Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

What do you get when you mix together a mishmash of ethnicities, a powerful political union and an exodus of emigrants, then let it stew for several generations? We’re referring, of course, to the genealogical goulash cooked up by the Austro-Hungarian Empire. By the time Eastern European immigrants were flocking to America (1880s to 1920s), Austria-Hungary had swallowed up the center of the Continent — including areas of present-day Croatia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Ukraine in Hungary’s domain.

As a result, the 1.4 million Americans who claim Magyar ancestry share their Hungarian roots with people whose ancestors came from all over Eastern Europe. They also share a number of genealogical challenges: confusing geography, unfamiliar languages, and surname and place name changes.

If you’re hoping to trace your family tree in Hungary, this might sound like a recipe for disaster. But don’t let the challenges discourage you — follow these five steps to satisfy your hunger for family history.

1. Do your prep work

Before delving into Hungarian research, you’ll need to assemble some tools and ingredients. Start by jotting down what you already know and what you want to find out. Ask your parents, aunts, uncles and cousins for names, dates and — most important — places (especially town/village names) to steer your initial research. Be sure you also ask them for any written documentation to back up their claims. Then load up on the research guides in the toolkit and do some legwork:

Learn your history

The Magyars originated in Asia and settled in what’s now Hungary — along the Danube River in the Carpathian Basin — in 896. For the next 100 years, the Magyars raided the kingdoms of Europe until they eventually met their match in the Germans.

Over the next few centuries, Hungary found itself on the other end of invasions — by the Mongols in 1241 and later the Turks, whose victory at the 1526 Battle of Mohács paved the way for Hungary’s royal union with the Hapsburgs of Austria.

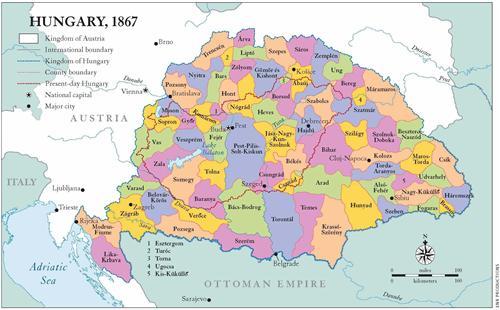

In 1867, Austria and Hungary established a dual monarchy, giving birth to Austria-Hungary. Austria controlled Bohemia and Moravia (the modern Czech Republic), Silesia (in what’s now Poland) and Galicia (divided between Poland and Ukraine), Bukovina (Romania), Carniola (Slovenia), Dalmatia (Croatia), Lower and Upper Austria, Salzburg, Tyrol, Carinthia, Austrian Littoral and Styria.

In addition to its modern-day territory, Hungary ruled Slovakia, Transylvania and Banat (in what’s now in Romania), Subcarpathian Rus’ (now in Ukraine) and the rest of Croatia, including Slavonia. Bosnia was jointly administered from 1878 to 1908.

The end of World War I spelled the end for Austria-Hungary — the peace treaties created Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia; Hungary also lost territory to Romania, Poland and Ukraine.

Understanding this geopolitical goulash — and the civil and ecclesiastical jurisdiction changes that came with it — is key to identifying and finding available records.

Get geographical aids

Modern maps might not show Great-grandpa’s village. To get an accurate picture of the region during his time, turn to historical atlases such as The Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of Eastern Europe by Dennis P. Hupchick and Harold E. Cox (Palgrave Macmillan) and Historical Atlas of Central Europe by Paul Robert Magocsi (University of Washington Press). Be sure to bookmark the Eötvös University cartography department’s online maps and Talma Publishers’ 1913 county maps.

You’ll also need gazetteers (geographical dictionaries) to research your ancestral village. We recommend the 1877 Magyarország Helységnévtára Tekintettel a Közigazgatási Népességi és Hitfelekezeti Viszonyokra by Janos Dvorzsák. Volume 1 indexes all Hungarian communities, with cross-references for variant names. Volume 2 gives each town’s county and district, along with religious statistics (number of residents who practiced each faith and churches they attended). You can view digital microfilm of this gazetteer from FamilySearch.org (search for microfilm numbers 599564 and 973041).

Check libraries for two helpful resources from Talma Publishers: Atlas and Gazetteer of Historic Hungary 1914 and Dictionary of Hungarian Place-Names by György Lelkes. The Hungarian Village Finder, Atlas, and Gazetteer for the Kingdom of Hungary CD, the Jewish-Gen Gazetteer and Radix’s Hungarian place locator also can help you pinpoint your family’s origins.

Try translation tools

Once you take your research back to the old country, you’ll encounter records in Hungarian, which differs from other European languages because of the Magyars’ Asian origins. With Hungary’s dominion once spanning so many ethnic groups, expect to run into other languages, too — including Latin, Slovak and German, among others. You don’t have to be fluent to decipher most genealogical records but a working knowledge of key terms and phrases will help. Start with the FHL’s genealogical word lists (download Hungarian, German and Latin Word Lists from FamilySearch.org); use the free online Hungarian-English dictionary at for quick lookups.

2. Devour US sources

The more genealogical clues you have to go on, the better off you’ll be when you venture into unfamiliar Hungarian sources. Focus your initial research on gleaning every scrap of ancestral information from American records, including:

Censuses

Tracking your family in federal censuses will help you identify the immigrant generation. For Hungarian genealogists, the 1880 through 1930 returns are most useful — with details such as native language (1920 and 1930 only) and parents’ birthplaces (generally just the country). You can search US censuses on the Web at Ancestry.com ($24.00 a month) and HeritageQuest Online (free through subscribing libraries), or view the schedules on microfilm from the FHL, major libraries or the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Use the five census research strategies from the May 2007 Family Tree Magazine to find your clan.

Passenger lists

From the 1880s until World War I, more than 650,000 Hungarians immigrated to the United States — and their passenger lists might reveal their hometown. You can search for New York arrivals for free at the Ellis Island Foundation and CastleGarden.org; Ancestry.com’s immigration collection covers New York plus all the NARA lists from other US ports. You can get the same records on microfilm from NARA, the FHL and some libraries.

Naturalizations

If your immigrant ancestor applied for citizenship, his declaration of intention (“first papers”) could indicate a place of origin. Immigrants could file in local, county or state courts, so check records from all three places (the FHL has many on microfilm you can rent via your local Family History Center. After 1906, courts had to forward naturalization records to the federal government; you can get copies from US Citizenship and Immigration Services (use the downloadable form. Fold3 ($79.95 a year) has indexes to naturalization petitions from New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Massachusetts, Louisiana and California (covering selected areas and years); some link to digital images of the naturalization records. Learn more about finding and using these records in the May 2008 Family Tree Magazine.

Vital records

Where available, request your ancestors’ birth, death and marriage records. Also seek out church records, which are more likely to document village names. Obituaries often reveal immigration details, too — especially those in ethnic newspapers. The University of Minnesota’s Immigration History Research Center (IHRC) houses a large Hungarian-American newspaper collection. See the Web site for details on requesting research for a fee.

As you use these sources, be sure to branch out beyond your direct lines. Chances are your ancestors put down roots among relatives, friends or others who hailed from the same village in the old country. Work sideways and check the above records for your ancestors’ siblings, cousins and neighbors.

3. Add your secret ingredients

Tracing your family in Hungary relies on two key ingredients — the immigrant’s name and the ancestral town or village. Some tips for researching them:

Names

An immigrant’s name is often your first stumbling block when you begin searching for records, especially online. Surnames that seem unusual to you — Balog, Horváth, Kovács, Nagy; find more at here — might be as common in Hungary as Smiths and Johnsons are here, making surname searches of databases and indexes impractical.

To use Hungarian records, you need to know your ancestors’ original name in the old country — which might have changed multiple times after their arrival in America. Ask your living relatives for all possible spellings, and don’t wholeheartedly believe Aunt Betty when she insists, “Our name has always been spelled this way” or “Our name was changed at Ellis Island.” (The latter is a myth; see this article from the New York Public Library to learn more.) Most immigrants changed their own names to sound more American: They Anglicized the spelling, chose an English equivalent or picked new names entirely. This also applies to first names. Uncle John might’ve been János in the old country, and Great-grandma Elizabeth, Erzébet. Two more naming traditions you should be aware of: Hungarians commonly put their family names before their given names, the reverse of most Western cultures. And women often won’t appear by their own name, but by adding the suffix -né to their husbands’ — for example, Great-grandma might show up as Kovács Mátyásné (equivalent to Mrs. Mátyás Kovács, or Matthew’s wife) instead of Erzébet.

Places

If you don’t know your ancestral town or village, building your family tree will be next to impossible. That’s because Hungarian records are stored and organized geographically — by county (megye), district (járás) and locality (község). Over time, county and district borders moved, and names changed. Of course, you’ll also encounter misspellings and transcription errors in US sources, so it’s important to determine the correct names. The map shows Hungary’s counties during the Austro-Hungarian period. Before 1918, many Hungarian records listed both a village and county name — for instance, Pósa, Zemplén. Try not to confuse the two: Pósa is the village; Zemplén is the former county. Use your gazetteers (step 1) to sort out those jurisdictional distinctions.

4. Chomp on church records

Now you’re ready to move on to the main course: Hungarian church records (egyházi anyakonyv). Although Roman Catholicism predominated throughout Hungarian history, Orthodoxy, Greek Catholicism, Protestantism (Lutheran, Reformed, Mennonite and Baptist), Judaism and even Islam also were practiced there. Prior to the October 1895 start of civil registration, religious authorities recorded all vital events. From 1781 on, each denomination maintained its own set of records. So to find your ancestors’ parish registers, it helps to know their religious affiliation.

Before 1781, however, the Roman Catholic Church kept official tabs on everyone — meaning your 18th-century ancestors will show up in Catholic records regardless of their faith. Record-keeping began when the Council of Trent (1545 to 1563) required parishes to maintain baptism and marriage registers; a directive to record burials followed in 1614. Unfortunately, most of the earliest registers haven’t survived, but coverage typically goes back at least through the 1700s.

The national archives in Budapest houses all ecclesiastical registers for modern Hungary. But you don’t necessarily have to travel there or hire a local researcher: The FHL has microfilmed many Hungarian church records up to 1895 — including ones for places now in other countries. To see if the films cover your ancestors’ locality, do a place search of the online catalog on the village name and look for a church records heading. If you don’t get results, expand your place search to the district and county. Try a keyword search on the town name, too — that will turn up sources referencing your ancestral village anywhere in the catalog record, not just in the place fields.

You can use gazetteers to identify the assigned religious jurisdiction for your ancestors’ town in the period you’re researching. If you can’t find your family in that parish’s records, try broadening your search. Perhaps your ancestors’ town didn’t have a church or synagogue for their faith, so they went to a neighboring parish. Also be aware that religious affiliation may not be static from generation to generation. If your family disappears from the church records, check other denominations.

What will the records tell you? Baptisms (keresztelo) include the child’s name, date (cluing you in to an approximate birth date), parents’ and witnesses’ names, and town of residence. Some Greek Catholic registers list the grandparents. Marriages (kázasság) typically give the date; the bride’s and groom’s names, residence, prior marital status and sometimes their ages; and the names of witnesses and possibly the parents. Burials (temetés) aren’t as detailed, but they’ll provide the decedents’ names, ages, last residences and perhaps marital status. For children who died, the records usually list the fathers. In general, records became more thorough — and easier to read and interpret — over time.

5. Take a taste of government records

Of course, you won’t want to limit your research to parish registers — you’ll need other sources to fill in gaps, expand your search and create a fuller picture of your family. Sample these next:

Censuses

The Austro-Hungarian Empire periodically enumerated its residents for taxation, conscription and statistical purposes. The four most genealogically useful censuses (népszámlálások) are from the 19th century: The 1828 land and property census, recorded in Latin, provides conscription information and property owners’ names. An 1848 census of Hungary’s Jews gives all household members’ names, ages and birthplaces. The 1857 census — in German and Hungarian or German only, depending on which form the enumerator used — gives all household members’ names and their relationships to the head of household, plus birth dates, religion, house numbers and sometimes place of origin. Likewise, the 1869 enumeration (in Hungarian) names all villagers, with details on their residences, ages, religions and relationships to the head of household.

The FHL has microfilmed many of these censuses; find them in the catalog by doing a place search for the county, then checking the census and census indexes headings. For others, try writing to the Hungarian national archives (see toolkit).

Military records

Because Hungary required service, your male ancestors will likely show up in military records. Muster rolls (katonai nyilvántartási jegyzék) list each soldier’s name, birth date, residence at the time of enlistment, and parents’ names. The FHL has microfilm of unindexed muster rolls for about 150 current Hungarian military districts. Unless you know what unit your ancestor belonged to, be prepared to search the records unit by unit.

During the dual monarchy, Austria and Hungary had one unified army. You’re most likely to find pre-1867 records for conscripts and officers at the Austrian State Archives’ war records division (staff will fulfill written requests for a fee). After 1867, Hungary began storing military records for its own districts. These documents are organized by regiment. To learn more, download “An Introduction to Austrian Military Records.”

Civil registrations

Hungary’s privacy laws restrict access to birth registers for 90 years, marriage registers for 60 years, and death registers for 30 years. So you’ll have just a few decades of civil vital records to work with after their 1895 start. The FHL has microfilmed many of the publicly available civil registrations (állami anyaknyv); they’re cataloged at the town level. When it comes to your Hungarian research, you can never have too many cooks in the kitchen. After you’ve exhausted these sources — or if you get stuck along the way — consider hiring a professional genealogist who knows the language and is familiar with the archive system. For referrals, try ProGenealogists, Radix, the Association of Professional Genealogists and Cyndi’s List. Posting to online message boards (see toolkit) and networking with other researchers can help, too. You may even get a goulash recipe or two.

Web Extra Download a chart with variant names, seats and current countries for all 71 old Hungarian counties.

A version of this article appeared in the November 2008 issue of Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT