Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

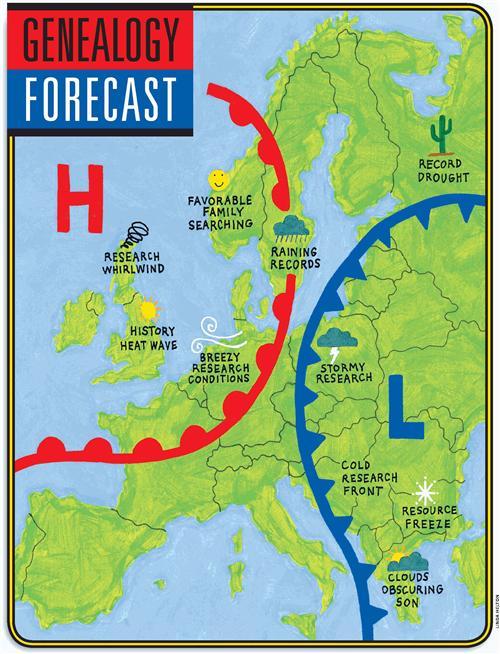

Depending where your ancestors came from, researching them might be a breeze – or rain showers might threaten to drown out your genealogical parade. Say you could choose your ancestry: What national origins would you wish for?

Being a genealogy magazine, we of course aren’t appealing to prejudice or national pride. This isn’t a question of whether the Welsh have more to brag about than the Moldovans, say, or if history chronicles more notable Poles than Danes. Rather, our interest is purely practical: Some overseas ancestral origins, having the most complete and accessible records going back the furthest in time, are smooth research sailing. On the other hand, certain foreign ancestries represent the most intractable challenges of record availability, accessibility and usability. These hurdles hamper hapless researchers with one cloudburst after another until they wish their ancestors had come from someplace – anyplace – else.

Will your genealogical quest have you living on cloud nine or chasing elusive rainbows? Our research outlook is news you can really use: Not only do we rank the five sunniest and stormiest ancestries – we also give you advice that’ll get you researching rain or shine.

Genealogy Climate Control

We studied several aspects of research conditions – sticking to European countries for space’s sake – in issuing this genealogical forecast. Here’s an overview of characteristics we looked at:

• Availability: Somebody back in the old country – typically a government or church – had to keep records. And certain nations outperformed others at tracking their citizens. Scandinavians, for example, kept downright persnickety records through the state-sanctioned Lutheran church.

You’ll turn to church records for most European ethnicities, as many governments have vital-record (“civil registration”) droughts: Croatia, for instance, didn’t start keeping them until 1945. But even meticulous records could have succumbed to wars or other misfortunes. Pre-1650 German records, for example, are scarce because of the Thirty Years War (1618 to 1648). During the 1922 Battle of Dublin, a blaze at the Four Courts burned almost all Irish census returns from 1821 to 1851. In general, warfare has taken the greatest toll on central and eastern European records, while those in Scandinavia and Great Britain are largely unscathed.

Well-intentioned but destructive neatniks struck, too. After compiling statistical data, Irish officials pulped censuses from 1861 through 1891. Sometimes multiple misfortunes wreaked their havoc, as with the emigration passenger lists from Bremen, Germany – Europe’s top departure port. Archivists authorized the ongoing destruction of all but the most recent records until 1909. Then WWII bombings did in many of the remaining manifests; less than two decades of lists (1920 to 1939) survive today.

Immigration records have their own issues. So many English arrivals to America came in Colonial times, when passenger lists are sparse, that finding your link back across the Atlantic may prove tricky. Luckier are those whose ancestors waited until after the 1892 opening of Ellis Island – they’re probably in the passenger database at <ellisisland.org>. Though people from all lands passed through the island’s “golden door,” this comparatively late crowd was heavy on emigrants from Italy, Eastern Europe and Russia.

• Accessibility: The biggest ancestral researchability wild card is records access. Even the most complete, best-preserved records stretching to the dawn of written history won’t help if you can’t get to them. Preferably, in this Internet age, all a nation’s most important genealogical records would be online for you to pore over in your pajamas. Sweden comes the closest to eternal sunshine here, thanks to the mammoth efforts of the subscription site Genline <www.genline.com>. Neighboring Norway excels at giving away data with Digitalarkivet <digitalarkivet.uib.no>. But the online-access champ is probably the Netherlands, thanks to the free site Genlias <www.genlias.nl>.

Many common ancestries, alas, lag behind in online records. German and Italian researchers, for example, can only look longingly at a site like Genlias. Their next best hope is that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) has microfilmed records – then they’re accessible through local branch Family History Centers (FHC). You can search the FHL catalog online at <www.familysearch.org>, and visit an FHC (find one using FamilySearch) to rent the film. The FHL has more than 28,000 rolls for Italy alone, primarily of civil registrations from the 19th and early 20th centuries. But even researchers with less-recorded ancestries will find happy surprises at the FHL: Church records from Hungary and Slovakia, for example, are microfilmed from the early 1700s to 1895, and Croatian church books on microfilm date to the late 1500s. It’s hard to declare a winner here, as FHL microfilming efforts have been so exhaustive for so many places, but notable gaps ding ancestries such as Russian in our rankings.

Even if the FHL hasn’t gotten around to your ancestors’ homeland, some countries make more genealogical bounties accessible than others. Archives in both Ukraine <www.archives.gov.ua/Eng/genealogia.php> and Belarus <archives.gov.by/eng>, for instance, at least have helpful Web pages – in English – with instructions on requesting records. Spanish researchers can consult several archival holdings catalogs at <en.www.mcu.es/archivos/CE/BaseDatos.html>, and find the archives themselves at <en.www.mcu.es/archivos/index>.

Say your ancestry’s records are plentiful. They’re still no good if you can’t tell where to look. Some ethnicities face more geographic challenges than others – victims of shifting boundaries due to wars, or lack of a clearly defined national homeland. In the classic case, German researchers talk about “Germanic” ancestors, because they don’t all fit within the neat boundaries of present-day Germany. “Germans” could hail from Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Alsace (France), Poland, Luxembourg, Denmark, the Czech Republic, even Russia. While England, France and Spain, among others, unified centuries ago, German-speakers only got together in a true nation-state when Otto von Bismarck became Germany’s first chancellor in 1871. Combine the country’s ever-shifting map with its place-name changes, and finding your ancestor’s village can be like harnessing a hurricane.

Geographic issues bedevil most ethnicities of Eastern Europe, where your ancestors’ “country” may have changed multiple times. Villages’ new landlords often renamed places with each new wave of conquest. The Federation of East European Family History Societies <feefhs.org> works hard to help researchers overcome such obstacles, but many of these ancestries remain among the most difficult to trace.

• Usability: Language can be another research barrier. Happily, you’ll find English is a de facto second tongue in many countries – notably in Scandinavia – which eases correspondence and Web surfing. You can study up on basic genealogy terms in 15 languages with the FHL’s word lists (go to FamilySearch and click on Guides, then Word List). But some languages’ traditional handwriting is particularly difficult to decipher. Early German documents are written in a style called Kurrent, which has several nearly identical characters.

Keep in mind, too, that although most European languages use the familiar Roman alphabet, many omit some letters and add others. You’ll need to know where these “extra” letters fall in the alphabet when it comes time to look up records. The winner in the language category is, of course, England, along with, to a lesser extent, other British Isles ethnicities. Irish researchers, thankfully, don’t face many Gaelic records, but they may have to deal with Latin, the language of government records until 1733 and some Catholic church records until the 1850s. Scottish researchers may stumble over Latin in documents as late as 1847, and on tombstones.

For researchers tracing a surname back through the ages, European ancestries can hold confusing surprises. The notion of an unchanging surname arrived relatively recently in Scandinavia, which for centuries used the patronymic system: A child would take his or her surname from the father’s first name. So if your dad’s first name was Anders, in Sweden your last name would be Andersson (Andersdotter for a girl); in Norway or Denmark, you’d be Anderssen or Andersdotter. Romania and Bulgaria also used patronymics, and Russians typically use a given name, patronymic and surname. The French gave their children multiple Christian names and nicknames, and some used two surnames (a family name plus what’s called a dit name).

Then, of course, come the puzzles arising from post-immigration name Americanization. They’re worst with the most-unfamiliar languages and alphabets – another strike against research in eastern Europe (František became Frank in the States; Vaclav turned to Wenzel) and the former Soviet Union.

On the other hand, some ethnicities help you with first names that are clues to previous generations. Italians traditionally named the first son after the father’s father, the second after the mother’s father and the third after the father; daughters’ names followed a similar pattern beginning with the father’s mother. Better yet is the tradition in Spain and Portugal, where married women keep their maiden names. Plus, children typically took both the father’s and mother’s surname, with the father’s name first in Spain and second in Portugal.

Given all these factors, how does your European homeland fare for family history research? Let’s review the rankings.

Storms Ahead

Don’t despair if your lot is among these five most headache-inducing ethnicities – from the merely challenging (No. 5) to the truly befuddling (No. 1). For each one, we’ll give you foul-weather research tips.

5. Polish

Don’t blame the much-put-upon Polish people for their place on this list. It’s not their fault their homeland lies between Germany and Russia, and has been invaded, occupied and divvied up so often as to make its historical map a crazy quilt. Even the Swedes have invaded Poland. Recent history has only added to the confusion: In 1999, Poland’s 49 provinces were reorganized into just 16. This unhappy history also brings linguistic surprises. Eastern Poland’s records from 1868 to 1917 will likely be in Russian; those in western Poland will be in German or Latin.

Casualties include records for Bremen, the port through which twice as many Poles left as via Hamburg, Germany (Europe’s No. 2 exit port). If you’re lucky enough to have ancestors who picked Hamburg, you may find them in Ancestry.com’s databases <Ancestry.com > (part of the US Deluxe subscription, which costs $155.40 per year). But even these emigration lists don’t routinely note the passenger’s home village or place of birth. On the bright side, many Poles arrived at Ellis Island and are listed in its database.

The FHL provides some help with your Polish ancestors: Its microfilms cover many parish and Jewish records, and about a half-dozen years of Prussian civil registrations, but no census records. FamilySearch does offer a Polish genealogical word list and letter-writing guide – no research outline, though.

Polish researchers also must grapple with Americanized names and a complex language whose alphabet totals a whopping 33 characters – and that’s without our Q and V. At least the national archives has a helpful site in English <www.archiwa.gov.pl/?CIDA=43>. You’ll also find assistance at the Polish Genealogical Society of America <www.pgsa.org>, which boasts a 970,000-entry database.

4. Greek

They don’t say “it’s Greek to me” for nothing: The ancient alphabet has characters most of us know only from math class or college fraternities. Worse, wars and invasions have wreaked havoc with the country’s records. Steamship service directly to the United States didn’t begin until 1907, so you must trace Greek immigrants through intermediary ports, such as Naples. When they arrived, many changed their names (try the Greek Name Translator at <www.daddezio.com/genealogy/greek/names.html>).

Once you trace an ancestor back to Greece, you need to know precisely where to look – district, county and town. Since civil registration didn’t begin until 1925, rely on church records, kept at the diocese level in larger cities. The FHL, alas, has a single reel of Greek church records and a mere handful of vital records on soldiers. Greek censuses date to 1828, but the FHL hasn’t microfilmed any, nor does it offer Greek research guides.

Understandably frustrated Greek genealogists may find help at the Greek Heritage and Genealogy Home Page <www.daddezio.com/grekgen.html>, the Hellenic Historical and Genealogical Association <www.helleniccomserve.com/genealogy.html> and Lica Catsakis’ Web site <www.licacatsakis.com>.

3. Russian

Of the ancestries that contributed major populations to our melting pot, Russian is arguably the toughest to research. Between its alien Cyrillic alphabet, war-damaged records and long period of Iron Curtain inaccessibility, the former Soviet Union can be a genealogist’s nightmare.

You may be able to trace your Russian ancestors’ route to America with the Ellis Island and Castle Garden <castlegarden.org> databases – more than 2.3 million Russians arrived between 1871 and 1910 – and Ancestry.com’s Hamburg database. Once you reach Russia, however, things get tricky, with shifting place names and remote records. The FHL has census records only from 1897 and for one province, just a smattering of church records from non-Orthodox congregations, and almost no vital records. Nor will you find any FHL research guides.

To make much headway in Russia, you’ll probably need to hire a researcher there. In the meantime, try the helpful tips at Researching Russian Roots <www.mtu-net.ru/rrr> and tools at Genealogia <www.genealogia.ru/en/main>.

2. Serbian and Montenegrin

Given the turmoil and ethnic strife that tore apart the former nation of Yugoslavia, your first challenge is simply figuring out what country now claims your ancestral place of origin. Here we’re referring to the nation that briefly remained after most of the former six Yugoslav republics broke away in 1992. Yugoslavia became the Union of Serbia and Montenegro in 2003; those nations went their separate ways in 2006. The Yugoslavia GenWeb site <rootsweb.com/~yugoslav> can help, and you’ll find the former Archives of Yugoslavia at the Archives of Serbia and Montenegro <www.arhiv.sv.gov.yu/e1000001.htm>. The FHL won’t be of much help. It has no microfilmed Montenegro records and only a handful of Serbian census, court and land records. Parish records prior to 1946 are in individual Orthodox, Catholic and Muslim churches. For records of areas once part of the Ottoman Empire, you may have to go all the way to Turkey.

1. Bulgarian

Pity the genealogist with roots in Bulgaria, an ancestry that manages to combine the most troublesome research-ability traits on our “worst” list. Unlike most East European ethnicities, Bulgaria doesn’t even have a hosted World GenWeb site (its orphaned site is at <rootsweb.com/~bgrwgw>). The FHL offers no Bulgarian research guides and essentially zero church, civil or census records; its few Bulgarian microfilms are mostly in Russian. The Bulgarian National Archives in Sofia doesn’t seem to have a Web site at all.

Sunny Outlook

Now for a much happier countdown of five fair-weather ancestries, along with the resources you should make a beeline for.

5. Dutch

The previously praised Genlias, all by itself, vaults researching in the Netherlands into our top five. A joint project of Dutch regional history centers and state archives, Genlias boasts 9.4 million records on 39.2 million people. Names come from the Civil Register, which dates to 1811, along with some parish records back to 1780. The fast-growing, easy-to-search site has more than doubled in scope in the first two years. And did we mention it’s free?

Where Genlias ends, the FHL takes over with various church records dating to 1550, plus notarial records full of clues to marriages, wills and property. The library has tens of thousands of Dutch microfilms and microfiches, plus thousands of books. You’ll also get plenty of help from its Dutch research guide, word list, map and gazetteer guides, and historical overview.

Dutch research isn’t without its challenges. Your “Frisian” ancestors may hail from the provinces of West Friesland or Friesland in the Netherlands – or from East or North Friesland, which are in present-day Germany. You also have to contend with historical handoffs of Dutch land back and forth among Spain, France, England and Austria. But once you overcome a few hurdles, the genealogical data can flow like, well, water through a hole in the dike.

4. Norwegian

Not only are your ancestors from Norway easy to trace, you’ll find plenty of fellow researchers both here and there: Only Great Britain surpasses Norway (along with Sweden) in the percentage of population immigrating to America. Norway’s detailed church records date to 1623, and more than 120 parishes boast records from before 1700. The FHL has extensively microfilmed these and other Norwegian records, creating more than 12,000 rolls of film and 3,700 microfiche. It also holds more than 3,700 volumes of Norwegian books and other print materials, including the United States’ largest collection of bygdebøker (Norwegian parish histories). Norway, like Sweden, is included in the FHL’s Vital Records Index and International Genealogical Index (IGI), both searchable gratis at FamilySearch. And Norway’s national archives’ has itself excelled at putting free information online, including the 1801, 1865, 1875 and 1900 censuses, plus passport records from Bergen (1842 to 1860), in Digitalarkivet.

True, Norwegians’ patronymic surnames can be confusing, often compounded by the habit of taking a second surname from the farm at which someone worked – which changed if he moved to a different farm. The alphabet has three “extra” characters: Æ (lowercase æ), Ø (ø) and Å (å). But so many Norwegians speak English that language is less a barrier than almost anywhere in Europe outside the British Isles. And there’s no shortage of help if you get stuck, including FHL guides and John Følles-dal’s invaluable Ancestors from Norway <homepages.rootsweb.com/~norway>.

3. Swedish

Besides writing down births, baptisms, marriages and deaths, most churches in Sweden took in effect an annual census and recorded families’ comings and goings. Despite its $365-a-year price tag and lack of an index, the aforementioned Genline (whose 16 million digitized images cover nearly all the country’s church records) gives Sweden an edge over neighboring Norway in our rankings. Swedish church records are also extensive, well-preserved and richly represented in FHL vaults, but it’s hard to beat the way Genline brings the best of a nation’s genealogical riches to your computer screen.

But that’s not all Swedish researchers can find online. SVAR (Svensk Arkivinformation), a branch of the national archives, is digitizing church records <www.svar.ra.se>, and it offers the 1890 and 1900 Swedish censuses (plus scattered 1860, 1870 and 1880 records).

Two CD sets provide unparalleled access and searchability to Swedish emigration records – again, for a price: Emigranten/The Swedish Emigrant (<www.goteborgs-emigranten.com>) and Emibas (<www.genlineshop.com>). The latter can identify your ancestors’ parish, enabling you to cross the pond.

The Computer Genealogy Society of Sweden, founded in 1980, is the world’s oldest such organization; search its DISBYT database <www.dis.se/denindex.htm> of 12.5 million member-submitted records for free (a $15 annual membership gives you more in-depth results). The Federation of Swedish Genealogical Societies offers its free Anbytarforum message boards and English-language assistance at <www.genealogi.se/roots>. Finally, the FHL has a complete set of guides for Swedish researchers.

On the downside are some extra alphabet letters – Å, Ä and Ö follow Z – and the patronymic system. Be aware, too, that during their compulsory military service, Swedes typically took “army names” to differentiate themselves from the oodles of other Anderssons, Jonssons and Magnussons who also enlisted. Some retained these new surnames after they immigrated to America.

2. Scottish

It’s no surprise that ancestries lacking a language barrier (unless you count that charming brogue) would lead our list. But Scottish researchers enjoy more than just easy record reading. Start at the FHL, which has at least a dozen guides to jump-start your family search, a wealth of microfilm and books (its online catalog lists 279 topics for Scotland), and the IGI (which you can search by parish via <www.scotsorigins.com>). Church records date from the 1600s, and civil records – held at the General Register Office <www.gro-scotland.gov.uk>, but available on FHL microfilm – take over in 1855. Decennial censuses are on FHL microfilm from 1841 to 1891; along with an index to the 1881 count.

What really makes Scotland stand out, though, is Scotland’s People <www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk> and its 50 million records. Differing fees apply, but without breaking the bank, you can search parish registers (1553 to 1854), vital records beginning in 1855, censuses (1841 to 1901) and wills and testaments (1513 to 1901). The related site Scottish Documents <www.scottishdocuments.com> lets you search more than a half-million wills and testaments (1500 to 1901), and some digitized church documents.

Scotland also has a handy naming tradition: Typically, the first son was named for the father’s father; the second son, for the mother’s father; the third, for the father; and the fourth, for the father’s brother. Girls’ names followed a similar scheme, starting with the mother’s mother.

1. English

That unpleasantness in 1776 aside, ties across the Atlantic remain strong, and the 25 million Americans with English ancestry enjoy enviable resources. Besides the guides and vast holdings of the FHL – whose catalog lists a whopping 511 topics for England – and the IGI, Family Search features a free 1881 British census index.

Web wise, that’s just for starters. Ancestry.com has more records from England than from anyplace besides the United States. For about $17.60 a month, British Origins <www.britishorigins.com> serves up 50 million names in Boyd’s Marriage Index, the 1841 and 1861 censuses (including images) and other records. FindMyPast.com <www.findmypast.com>, best known for vital-records indexes starting in 1837, has added emigration passenger lists, censuses and military records; you can pay per view or subscribe for about $250 per year. Other vital records options include BMDindex <www.bmdindex.co.uk> (subscriptions start around $10 per month, or pay as you go), and FreeBMD <freebmd.rootsweb.com>. Copies of records are readily obtained from the General Register Office <www.gro.gov.uk>.

The British national archives’ DocumentsOnline site <www.documentsonline.nationalarchives.gov.uk> grants you access to more than a million images of wills from 1384 to 1858; they’re free to search and cost about $7 per image. You can search the archives’ online catalog of its documents at <www.catalogue.nationalarchives.gov.uk>; also try Access to Archives’ <www.a2a.org.uk> search of 10 million records at 411 repositories.

For online assistance with this embarrassment of research riches, take advantage of GENUKI <www.genuki.org.uk> (the British Isles’ equivalent of USGenWeb) and the Federation of Family History Societies <www.ffhs.co.uk>, which also offers a paid database of parish registers, memorial inscriptions, censuses and more at <www.familyhistoryonline.net>.

ADVERTISEMENT