Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

If your ancestor belonged to the Modern Woodmen of America, at this point, he would need to give the Escort the appropriate “grip,” or handshake, and the required passwords.

Though some fraternal orders — organizations based on common interests or ideals — shrouded their rituals in secrecy, their enigma belies their popularity during our ancestors’ day. Millions of Americans joined the ranks of thousands of Societies, especially in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1896, for example, fraternal orders had more than 4.7 million total members — which was about one in every eight US adults. So there’s a good chance that you have a Freemason, Odd Fellow or Knight of Pythias in your family tree.

And it’s no mystery why fraternal orders appealed to so many men (and women). These organizations provided a significant form of fellowship for our ancestors — the societies gave them the opportunity to interact with people who shared their religion, occupation, social status, ethnicity or philosophical beliefs. The Woodmen s creed, as it appeared in the Official Ritual of Modern Woodmen of America 1939, sums up the reason our ancestors joined fraternal organizations with such fervor:

There is a destiny that makes us brothers; None goes his way alone; All that we send into the lives of others Comes back into our own.

You won’t need passwords or grips to discover this cryptic-but-captivating aspect of your family history. Despite any clandestine rituals and activities, fraternal societies left plenty of clues about their pasts. And your ancestors may have left evidence of their own involvement. Use these research secrets to learn which groups your forebears belonged to and what their membership can reveal about their lives.

Bands of brothers

Although membership in fraternal societies has declined since their heyday a century ago, numerous orders still exist. The more-modern groups — including those our ancestors joined — evolved out of ancient Roman “burial clubs,” associations that offered members the equivalent of life insurance: The clubs collected dues at regular meetings to pay for members’ funeral costs.

From the burial clubs, guilds (confederations of people practicing the same trade or profession) began to form during the Middle Ages. In addition to offering financial and emotional support, guilds bound their members to protect trade secrets. Such groups later came to be known as voluntary benefit societies (because many provided insurance benefits) and, in Great Britain, friendly societies.

In 1717, the Freemasons were born in London. This new group rook its name from the city’s original four “lodges of operative masons” — guildlike alliances of stonemasons. The group developed a centralized structure known as the Grand Lodge. Members were prohibited from divulging the organization’s secrets.

The Freemasons have a long history in America, going back to Colonial times: Pennsylvania’s Grand Lodge was created in 1731, Massachusetts’ in 1733, Georgia’s in 1735 and South Carolina’s in 1737. Their rituals became the basis for many of the other secret societies our ancestors joined. Newer orders borrowed the Freemasons’ “lodge” structure, too. (For more about the Masons, see the opposite page).

Of course, fraternal organizations weren’t all based on professions — nor were they all super-secret. Thousands of societies formed, from the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine (a Masonic order also known as the Shriners) to Zonta International. They fall into seven categories:

• Social: These groups trace back to late 18th-and early 19th-century drinking clubs, which allowed like-minded individuals (usually men) to get together for a drink and perhaps conversation or games. Some of today’s best-known fraternal organizations, including the Freemasons and Odd Fellows, could be considered social societies.

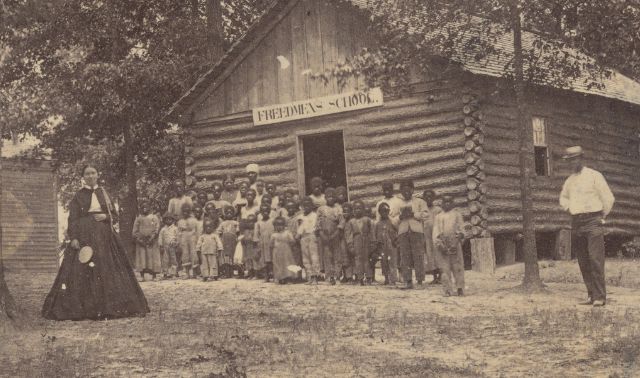

• Benevolent and service: The broad goal of these good-Samaritan societies is helping others. Benevolent organizations exist generally to help their own members; service societies primarily assist charities. Benevolent societies started as a 19th-century form of welfare: They offered assistance when members got hurt, died or lost their jobs. Immigrants often joined this kind of organization because they seldom had large families to turn to in America.

Despite the distinction, benevolent and service societies often overlap. For example, the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, a benevolent society, also assists local and national charities. The Lions and the Rotary Club are primarily service organizations, but they help their own members, too.

• Ethnic: As Europeans came to America en masse in the late 1800s and early 1900s, immigrants of the same ethnic heritage formed their own fraternal organizations. For example, Italian-Americans established L’Ordine Figli d’Italia, or Order Sons of Italy. These ethnic-based societies served three purposes. First, they allowed members to maintain a link to the old country: People exchanged news from back home, and reminisced about the lives they left behind. Secondly, ethnic societies preserved Old World traditions and culture, so the immigrants’ children (and future generations) could know their heritage. Finally, the groups provided insurance for immigrants, who often worked long hours in harsh conditions at mill, factory, mining and other industrial jobs.

• Trade: Occupation-based organizations grew from workers’ need to band together — usually for collective bargaining.

Their objective often was insurance; workers in certain trades couldn’t get coverage because their jobs were deemed too dangerous. Some trade societies resembled (or became) labor unions. For example, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, founded in the 1860s, is now part of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

Trade organizations also acted as support networks. For instance, the Grange — officially called the Patrons of Husbandry — was much more than a group of farmers attempting to get better prices for the wheat and other crops they grew. It encouraged service to others, and was the first fraternal society to admit women.

• Religious and mystical: Knowing your relative’s religion may narrow your research into fraternal groups. For instance, if you have Catholic ancestors, you’ll want to investigate the Knights of Columbus. Father Michael J. McGivney founded this organization in 1882 so Catholic men could join a fraternal order without defying papal decrees — the Roman Catholic Church had prohibited participation in secret societies since 1738.

Membership mysteries

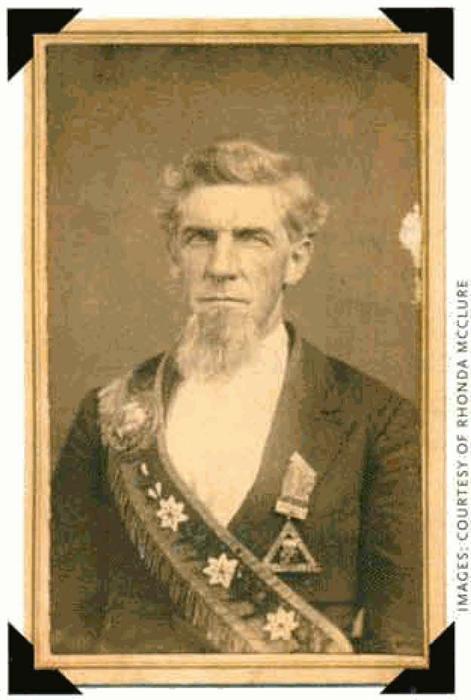

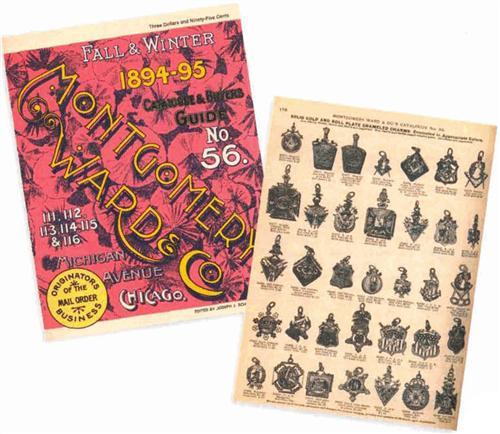

Suspect your ancestor belonged to a fraternal society (or more than one)? Certain clues can help you confirm your hunch — an insignia on Grandpa’s tombstone, for example, or a piece of jewelry. Though many fraternal organizations required members to take oaths of secrecy, those vows applied primarily to the groups’ ceremonies. Members could — and did — openly acknowledge their society affiliations.

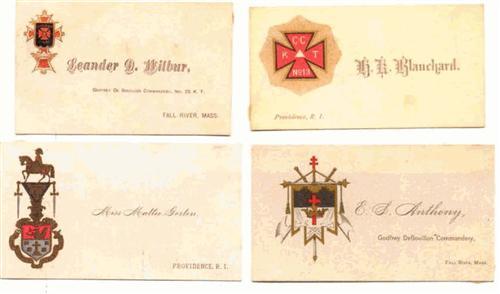

In fact, our ancestors took pride in belonging to fraternal societies, and weren’t shy about showing off their membership: They wore jewelry with their groups’ signs, put the insignias on their stationery, and had their pictures taken in full fraternal regalia for cartes de visite (photographic calling cards), which they gave to friends and associates. Members displayed their loyalty even in death, having their orders’ insignias engraved on their tombstones or on flag holders placed in the ground nearby.

For members, these symbols were badges of honor; for you, they’re genealogical evidence. So learn to recognize fraternal insignias — especially which ones belonged to which groups. You’ll have an easier time placing your ancestor in a particular society. You can study those signs online: The Web sites at left show regalia and jewelry bearing the icons, acronyms and insignias of different orders. Be sure to check the individual societies’ Web sites, too.

If you haven’t found these clues yet, you still can investigate fraternal organizations that might have appealed to your ancestors. Start by writing down everything you know about Great-grandpa’s religion, occupation and ethnic heritage.

Then research which organizations were active where he lived. You can turn to two sources: City directories contain details about local societies, including their names, locations and even meeting nights and times. County histories sometimes give information about the formation of fraternal societies, allowing you to determine whether a society existed when your ancestors lived there. These are the best sources to check if your family lived in a rural area where city directories weren’t published.

From this research, create a list of the organizations Great-grandpa most likely belonged to. Be careful nor to rule out possibilities too quickly, however. You might assume that Great-grandpa didn’t belong to a certain group simply because of its name or nature, but society names can be misleading. For example, many people think the Improved Order of Red Men (IORM) is a society for American Indians. Until recently, though, the IORM (founded in Baltimore in 1834) was open only to whites — in fact, the society specifically banned American Indians from joining, even though its stated aim is “to perpetuate the beautiful legends and traditions of a vanishing race and to keep alive its customs, ceremonies and philosophies.” And in my trips to Catholic cemeteries, I’ve found numerous tombstones bearing insignias for non-Catholic orders, including the Modern Woodmen of America, the American Legion and the Maccabees.

Record revelations

Once you’ve discovered a link to a particular organization, you’d naturally want to see your ancestor’s membership records. What will those documents reveal? Don’t expect data that will add generations to your family tree. Instead, the records will likely show you the date your forebear became a member or the date of his arrival at that local lodge, as well as the offices he held. You might discover a lodge history that contains pictures — maybe even one of your kin. Essentially, you’ll get details that illustrate your ancestor’s personality.

Finding records for any fraternal group requires a certain degree of tenacity. Unlike census records and other common genealogical sources, fraternal societies’ records aren’t as readily available on microfilm, at libraries and on the Internet.

Still, you first should check familiar research repositories such is the church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> and its branch Family History Centers (FHCs — from the FHL home page, click on Library, then Family History Centers to find one near you), local and county genealogical societies, and state and local archives — some have fraternal-society collections. For example, the University of Minnesota’s Immigration History Research Center <www.familytreemagazine.com/articles/aug03/libraries.html>. You can search the FHL’s catalog online at <www.familysearch.org> (click on Library, then Family History Library Catalog). To see what records the FHL. has about a particular society, perform title and author searches on the organization’s name.

If you don’t turn up records in any of those places, they’re most likely at a local or state lodge, or the organization’s headquarters. To find out, contact the society’s nearest branch. Even if your relatives wouldn’t have belonged to that lodge, someone there probably can tell you where the organization keeps its records (in a central location or individual lodges), what information those documents contain and whether you can get copies. (Remember: Fraternal orders are private organizations; unlike government agencies, they aren’t required to open their records to the public.)

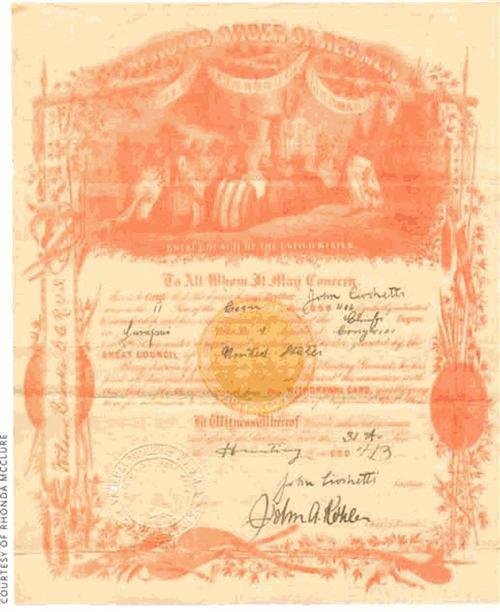

Of course, tracking down information gets more challenging when you’re searching for records of a defunct society. Many of the groups founded in the 1800s have faded into extinction over the years. Even “secret” societies leave paper trails. This Improved Order of Red Men withdrawal card certifies that the signer paid all his dues and has permission to join another tribe.

Some, such as the Loyal Sons of America, had very short lives: Founded in Newark, NJ, in 1920, this order paid illness, disability and funeral benefits to members. It also emphasized “absolute protection of, and a continuous vigilance over, our free public schools.” The Loyal Sons of America anticipated a membership of 5 million; however, by 1923, the group had only 515 members, and soon disbanded. In other instances, small societies have been folded into larger, more powerful organizations. For instance, the Royal League was founded in Chicago in 1883 as an offshoot of the Royal Arcanum. The Royal League absorbed the Order of Mutual Protection in 1932, and then it merged with the Equitable Reserve Association <www.equitablereserve.com> in 1970.

Understanding the background of your ancestor’s fraternal order can help you determine where and how to look for records. Consult Alan Axelrod’s The International Encyclopedia of Secret Societies & Fraternal Orders (Checkmark Books), which gives background, history, addresses and recent membership figures for active societies. It also outlines which groups have merged and absorbed other organizations. Axelrod’s work doesn’t outline every order that ever existed, but it’s a valuable tool for any fraternal-society research.

Also check public and university libraries for histories of specific orders. These books usually outline an organization’s growth, so you can use them to determine when a group arrived — or left — your family’s area.

Finally, don’t overlook the Web: It’s an invaluable tool for histories and background information. Many active fraternal orders have Web sites that describe their origins and activities. If you do write the national offices, remember to be courteous and patient. After all, the staff’s job is to offer support to members — not genealogists.

Just in case that doesn’t work, you might want to start practicing the secret handshake.

ADVERTISEMENT