Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

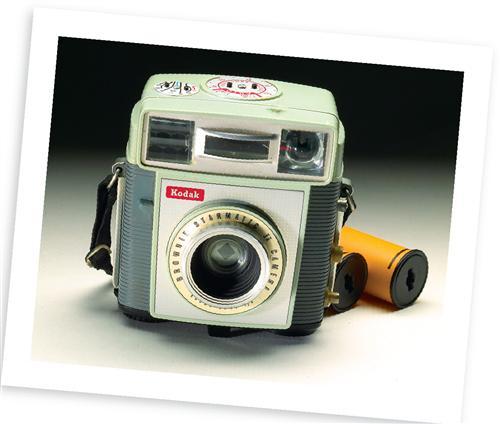

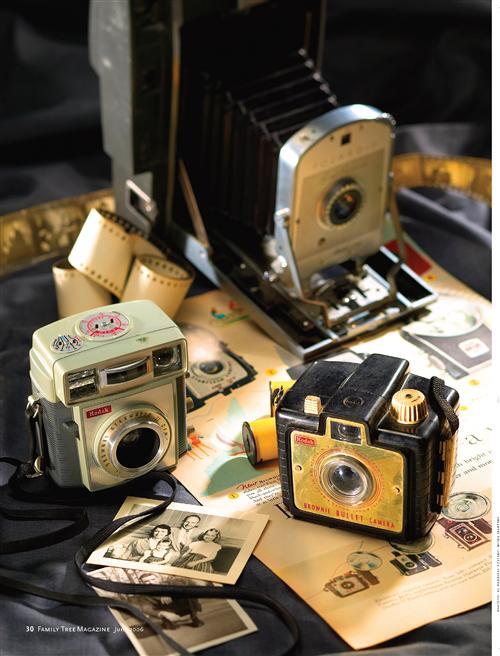

The 20th century saw life-altering inventions such as the television, microwave and computer. But in my book, one revolutionary innovation tops them all: the Brownie camera. Kodak <www.kodak.com> introduced it in 1900 with the whopping price tag of one buck and a promise that “any school-age boy and girl could easily operate it.” Consumers agreed — Kodak sold a quarter million Brownies that first year.

Photography changed forever: Once children started snapping pics of their pets, friends and families, so did their moms and dads. Everyone learned to say “cheese!” and the click of a shutter imprinted itself into our brains. The number of pictures families snapped and stored skyrocketed, but people rarely paused to give them labels. How do I know this? Family historians are submitting these photos — some taken as recently as the 1970s — to my online Identifying Family Photographs column <www.familytreemagazine.com/photos/current.htm>. Identifying these recent images is different from working with older photos: For one thing, the size and shape of a 20th-century image doesn’t give you a clear-cut time frame. But you can date your 20th-century photos — if you focus on these six secrets.

1. Ask and ye shall receive.

Relatives are your best photo-identification tools. If your unidentified picture was taken in the last 50 years, it’s quite likely someone recognizes the people in it or even attended the event. Memories are relatively fresh even for early-1900s occasions, so take copies of mystery images to family gatherings and e-mail digital versions to far-flung cousins.

Look at your genealogy charts and files, too: Some pictures probably depict the graduations, weddings, christenings, first communions and birthdays you’ve been researching. Make a timeline of all your family events and try to match them with your pictures. Say you have a 1905 wedding picture, and your charts say Great-aunt Alberta and her husband Herb are your only relatives married around that time. It’s a pretty safe bet they’re in the photo-just make sure the rest of the clues (which we’ll cover in this article) add up. Also try to guess the ages of the people pictured, especially children. If a portrait shows your grandmother, three children and a baby, and family charts list the last of four children born in 1923, you can date the photo around that time.

2. Consider negative aspects.

If you’re lucky enough to have negatives, pay attention to the composition and dimensions, and note whether they’re on a sheet or in a strip of roll film. These factors can help you identify the type of camera used, which gives you a time frame — but that’s a tricky tactic because families used cameras for generations, and manufacturers produced film for them just as long. For example, Kodak introduced its black-and-white roll film 101 in 1895 and didn’t discontinue it until 1956.

Three types of early black-and-white roll film look similar because they’re all made on clear plastic strips, but they contain different light-sensitive chemicals. Photographers began using a gelatin film in the 1880s, and cellulose acetate — marked safety on the edge — has been in use since 1939. Thin, highly combustible nitrate film, which curls and wrinkles easily, was available from 1889 to 1903 (see the box on page 34 for instructions on safely handling any nitrate negatives you may have around the house). Sheet film stamped Eastman on the edge dates from 1913 to 1939. You’ll find information on Kodak cameras, their film sizes and manufacture dates at <www.kodak.com/global/en/consumer/products/techInfo/aa13/aal3.shtml> and <www.nwmangum.com/Kodak/FilmHist.html>. Anyone remember disc film and the Polaroid <www.polaroid.com/us> Swinger? A disc of negatives places pictures in the 1982 to 1990 time frame.

3. See how your prints measure up.

In all likelihood, you don’t have negatives, just prints. Determining the photographic method brings you closer to an ID for 19th-century images, but paper prints have dominated for the entire 20th century. Just think about all the cameras you’ve used since you were a child — if you’re like me, you’d need more than two hands to count them. Their styles vary so much that a picture’s shape or measurement might help a little, but it’s hard to tell which type of camera made a print. Although your best clues come from what’s in the photo, these broad categories of print types will help date a photo, too.

• Snapshots: Quick-and-easy photography brought about the term snapshot, which refers to any candid photographic print taken with a hand-held camera. The box cameras of the 1880s to the mid-20th century produced a variety of different-size pictures. See The History of Kodak Roll Films online at <members.aol.com/chuck02178/film.htm> for a list of print sizes produced from these cameras. If you have circular images in your family photographs they may date from about 1900. Mid-20th century prints have deckled edges. Standard print sizes today are 4×6 and 3×5 inches.

Black-and-white snapshots left color to the imagination, but only until Kodak introduced color negatives and prints in 1941. You’ll find a good overview of color photographic processes, along with information on how to care for your photos, in The Permanence and Care of Color Photographs by Henry Wilhelm and Carol Brower (Preservation Publishing).

Your snapshot may talk to you, after a fashion. From 1914 to the 1930s, Kodak offered an autographic system. A photographer could flip open a little window on the back of the camera and use a metal stylus to write a date or location right on the film. The notes would show up in the margin of a processed print.

If your photo looks cracked, it may date from the 1960s. That’s when a shiny, resin-coated paper became popular because it reduced processing time and didn’t curl when drying — but it also tended to develop telltale cracks over time.

• Postcards: If you turn over a portrait of Great-grandpa Eugene and the back looks like a postcard, you have a “real photo” postcard. These actual photographs, produced from film or glass-plate negatives with postcard-style backs, appeared around 1900 and remained available for decades.

You can use design elements on the back of the card — such as the sections for correspondence and address, and the “place stamp here” box — to estimate a date. Compare the stamp box style and wording with those shown on Playle’s Online Auction site <www.playle.com/postcards.html#realphoto>, which gives date ranges for each type of box. If your postcard was mailed, research the name and address on the card in city directories. Also see <www.playle.com/datingpostcards.html> to date it using the postage amount. Look up the stamp and postmark in philatelic (stamp-collecting) guides and on Web sites such as <www.postalmuseum.si.edu> and <ajward.tripod.com/stamps/links.htm>. (Remember, the sender may have used more than the required postage, and may have kept the card a while before mailing it.) See the October 2005 Family Tree Magazinefor more on photo postcards.

• Stereographs: You may have seen a stereograph and wondered why someone would want two nearly identical pictures mounted side by side. They were for entertainment: Peek at the photos through a special viewer, and you see a 3-D image. Starting in 1854, a few commercial companies produced “stereos” of travel, war, religious and other scenes — rarely do they depict people. Your relatives might have purchased these double images, but they most likely wouldn’t show your family. So a stereograph won’t tell you when your great-grandma married, but it will tell you something about her interests.

Research the photographer or publisher, title and subject — usually printed on the back — to date the image. Learn more about your stereos in Stereo Views: An Illustrated History and Price Guide, 2nd edition, by John Waldsmith (Krause Publications) or Stereo Views: A History of Stereographs in America and Their Collection by William C. Darrah (Times and News Publishing Co., out of print).

• Slides: These little square images in plastic or cardboard mounts are older than you think: Glass slides appeared in the late 19th century. Auguste and Louis Lumiére introduced the autochrome, the first commercially successful color photography process, in 1904. The brothers used starch grains dyed red, green and blue to create a glass slide viewable with a device dubbed a diascope. Generally, professionals took autochrome photographs, so they rarely appear in family collections. Take a look at them in The Art of the Autochrome: The Birth of Color Photography by John Wood (University of Iowa).

Kodak offered the first amateur color slide film in 1936. It’s still available today, although Kodak no longer manufactures slide projectors or trays. Unless you’re lucky enough to have slides in paper or plastic mounts with a stamped or embossed processing date, you’ll have to rely on what’s in the photo for a more-specific date. And since digital imaging is rapidly replacing slides, you should convert them to other media: Either scan them with a slide scanner or have a photo lab make prints.

• Polaroids: In 1947, Edwin Land patented his process for instant photographic gratification, and Polaroid still makes film and cameras in a variety of formats. You can date some pictures by their sizes and others by the codes on the backs, which tell when the film was manufactured but not when it was purchased or when a photo was taken. Different Polaroid films (such as 600, 500, SX-70 and peel-apart) use different types of codes, so determining a manufacture date can be tricky. To get an estimate of the film’s age, go to Polaroid’s Web site, click Support and then Ask Polaroid, select Instant Imaging, and e-mail the code and film type. You also could contact the company’s customer service department at (800) 343-5000. If you know the camera model your family shutterbug used, learn more about it by clicking the Answers tab and using the pull-down menus to select the model, then click Search.

4. Collect content clues.

Generally, the most important clues for a 20th-century photo aren’t its size and format, but its content — objects, events, fashions and people — as well as family stories of those photographic moments.

• Objects: The 20th century is the age of consumer goods, so take out a magnifying glass or enlarge the picture with photo-editing software to examine cars, bicycles, appliances and other items in your pictures. Go to <www.oldcartrader.com> and dad’s little red Corvette could give you a time frame. The same item popping up in a series of photographs taken over a decade won’t supply a specific date, but it will provide a date range for those pictures. Many families held on to appliances, televisions, cars and other expensive items until they wore out, but more-disposable goods such as toys narrow the time frame. Remember yo-yos, hula hoops and the first Barbie dolls? Look for them in 20th-century collectibles guides such as Toys & Prices 2005 edited by Karen O’Brien and Antique Trader Antiques & Collectibles Price Guide 2005 edited by Kyle Husfloen, both from Krause Publications. You also can find out when everyday items such as calculators and toasters became popular by reading period magazines at your public library, consulting Web sites and asking your family.

Background: Point-and-shoot cameras let relatives snap pictures anytime, anywhere. That means something in the background might ring a bell. Look for posters and other signs, parades, sporting events and festivals. Do family stories tell of cousin Ethel witnessing American Babe Didrikson’s javelin throw victory in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics? If you can guess the event in the photo, you can use a timeline or chronological encyclopedia of events to assign a year — and possibly a day. Any library has illustrated histories such as National Geographic Eyewitness to the 20th Century (National Geographic) or 20th Century Day by Day edited by Clifton Daniel (DK Publishing). Read local newspapers and, if it’s a school event, yearbooks. Large libraries often have old newspapers on microfilm, or see the September 2005 Family Tree Source-book, a special issue of Family Tree Magazine, for online newspaper sources. You can find yearbooks at school libraries and local historical societies.

Examine buildings, bridges, geographical features and streets, too. Research business names using city directories to narrow the time frame. You have a date if you can identify a building under construction, and landmarks supply the geographic location.

Weather conditions also can suggest a season or even a date. How many parents photograph their bundled-up children holding a yardstick in a snowdrift after the blizzard of the century? Local newspapers report on snowstorms, hurricanes and other weather phenomena, so guess a photo’s time frame, then head to the library to scan dailies and weeklies.

Fashion fads: Women often repeat the adage “Wait 20 years and it’ll come back in style” because they’ve witnessed the fluctuating fashions of the 20th century. Case in point: Skirts shrank from ankle-length in 1900 to the micro-minis of the 1960s. That means the length of a woman’s dress can help you decide if a picture was taken in the 1940s or the 1960s. Some fashion details are immediately recognizable: the dropped-waist, shapeless dresses of the 1920s, small feathers atop the hats of the 1930s, broad-shouldered dresses of the 1940s, pencil skirts of the 1950s, tie-dye T-shirts of the 1960s and bell-bottom pants of the early 1970s.

Men’s fashions also changed with the times, incorporating bolder patterns and colors as the century progressed. During the early 1900s, gentlemen wore narrow coats with white shirts featuring high, stiff collars, and accessorized with narrow ties or black bow ties. They wore their hair short with large mustaches.

Both sexes sported sunglasses starting in the 1930s, and love beads, which became popular in the 1960s. Keeping up with 100 years of style is a cinch if you consult John Peacock’s 20th Century Fashion and Fashion Accessories: The Complete 20th Century Sourcebook, published by Thames and Hudson.

Children’s clothing usually mimics adult fashions, but a trend toward unique outfits for youngsters developed in the late 19th century. Mass-produced clothing sold in catalogs let mothers dress their offspring as children rather than miniature adults. Explore the choices for kids from tots to teens in Children’s Fashions 1900-1950 as Pictured in Sears Catalogs edited by JoAnne Olian (Dover Publications).

Closely inspect military uniforms and outfits, such as sports uniforms, worn for activities. Research the history of a sport to find examples of period uniforms and equipment. Look for years on letter sweaters and college jerseys, and compare your photos to those in school yearbooks. Standard military dress appeared around mid-century, making dating photos easier. Before then, you’ll find variations in uniforms, insignia and medals. Consult William K. Emerson’s illustrated Encyclopedia of United States Army Insignia and Uniform (University of Oklahoma Press) or I.T. Schick’s Battledress: The Uniforms of the World’s Great Armies 1700 to the Present (Artus Co.) for more details.

5. Name the shutterbug.

As the family picture takers became more experienced with cameras, the line between professional and amateur portraits blurred. It’s not always clear whether a studio photographer or Uncle Stan clicked the shutter. Don’t be fooled by a relaxed pose or everyday clothes — some professionals began to pose subjects more naturally in the late 19th century. To add to the confusion, in the early 20th century, Kodak made and processed cardboard mounts for consumers similar to the ones studios used.

To tell whether you have a studio or home shot, look for a photographer’s imprint, which might be embossed or printed on the back or front of the picture. Professionals often used props and cloth backdrops, too, and many photographers eventually switched from mounts to folding enclosures bearing the studio name. If you have a professional shot, look up the business in city directories. Whether your shutterbug was a pro or Uncle Stan, you’ll find advice on researching the person holding the camera in the August 2005 Family Tree Magazine.

6. Protect the past.

Nineteenth century photographs may outlast their 20th-century descendants. Early-1900s black-and-white prints develop a silvery sheen as they age. Color photography is inherently unstable — for example, Koda-color film negatives may be damaged and unprintable; the prints originally made from them, stained yellow and illegible. Even photos from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s may show fading and discoloration.

Heat, sunlight, strong fluorescent light and humidity cause most of the problems, but poor-quality papers and chemicals contribute. Some pictures look redder as they age; others, more yellow. Certain Kodak prints available from the 1950s through 1970s fade regardless of how you store them. Lacquer, which photo processors applied to color prints to prevent damage, can discolor. Surface cracks appear on photos printed on quick-drying resin-coated paper, and Polaroids can develop cracks between the plastic layers. You can slow the deterioration by taking these measures:

• Keep photos in a dark place with stable temperature and humidity levels, such as an interior closet adjacent to a living area. Avoid the attic, garage and basement.

• Handle prints by the edges so you don’t leave fingerprints.

• Interleave prints with acid-free tissue (to keep them from sticking together) in archival photo-storage boxes, or place them in an acid- and lignin-free album. Find these materials at art-supply and scrapbook stores, or online retailers such as Archival Methods <www.archivalmethods.com>.

• If prints are stuck together, consult a photographic conservator. Use the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works’ <aic.stanford.edu> free online referral service.

• Hold on to negatives so you can make new prints of lost or damaged photos. Store them in acid- and lignin-free paper sleeves. (Temperature and humidity changes can make negatives stick to plastic sleeves.)

• Black paper albums are acidic, but leave the photos in them — any damage probably has already occurred.

• Remove photos from magnetic albums if possible. If they’re stuck, scan the pages to preserve the content of the photos, and consult a conservator.

• See the April 2004 Family Tree Magazine for instructions on scanning and digitally repairing your faded, discolored or cracked photographs.

• Don’t throw out old, undeveloped film lying around the house. Depending on the film’s age and condition, you might be able to have it printed. Rocky Mountain Film Laboratory <www.rockymountainfilm.com> can develop most formats.

Fire Escape

Nitrate negatives, in use between 1889 and 1903, are so hazardous that museums copy them and destroy the originals to avoid the threat of spontaneous combustion. Your risk may be negligible unless you’re storing a large number of these negatives in an area with temperature fluctuations, such as an attic. Any negative not marked safety could be nitrate. To tell for sure, cut off a small section of the negative and place it in a nonflammable container. Then try to ignite it with a match. If it burns, it’s nitrate; if it doesn’t, it’s unmarked safety film. Contact a photo conservator for information on copying nitrate negatives — you won’t be able to mail them because of the fire risk. After duplicating them, ask your local fire department how to safely dispose of the originals.

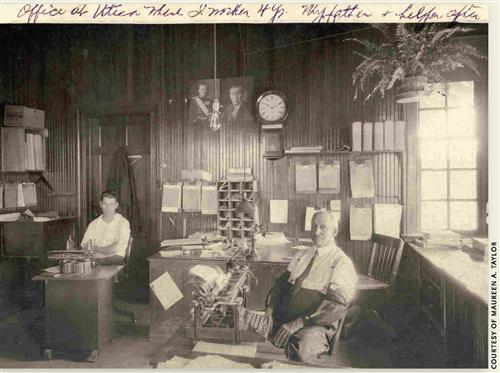

1. Clues in this photograph include which objects?

a. the typewriter, the portraits on the wall and the fern

b. the typewriter and the portraits

c. just the portraits

2. This picture was taken

a. while these workers were burning the midnight oil (which explains why they’re not smiling)

b. at 10:10 a.m.

c. after lunch

3. The light bulb proves this photo was shot

a. after the Mesozoic era

b. after 1879

c. none of the above

4. Men of the 1920s often accessorized their outfits with dark sleeve covers such as the ones on the older man.

a. true

b. false

c. What covers? Those stains are how

I know the photo was taken after lunch.

5. The US president in the portrait nearest the clock is

a. Woodrow Wilson

b. William Howard Taft

c. George W. Bush

6. The typewriter dates to

a. 1957

b. Isn’t that the first fax machine?

c. the early 1900s

7. According to the caption, these men work in

a. prison

b. a Boston suburb

c. Utica

8. This picture was taken after 1913.

a. true

b. false

1. b. The plant is real, but it can’t tell you when the picture was taken. Researching typewriter models will help you determine a time frame, as will identifying the portraits (see answers 5 and 6).

2. b. The sun streaming in the window shows it’s morning and the clock on the wall gives the time.

3. c. The first answer is technically correct, but not very specific — we can’t in good conscience give you the point. Thomas A. Edison is often credited with inventing the light bulb in 1879, but historians dispute this. Check out the true story of the light bulb at <www.coolquiz.com/trivia/explain/docs/edison.asp>.

4. b. Most male office workers wore shirts, ties and jackets (these fellows hung their jackets on the door). The older man’s dark sleeve coverings protect his shirt from ink stains, indicating he works in a printing-related business.

5. a. This is Woodrow Wilson, who was president from 1913 to 1921. (We’ll give you a bonus point if you pulled out your magnifying glass.)

6. c. This typewriter, with its large, raised roller, resembles the early 1900s models shown on TypewriterCollector.com <typewritercollector.com >.

7. c. Utica, but according to the Census Bureau, more than 20 places have that name (see <www.census.gov/cgi-bin/gazetteer>). One way to find more information: Use the Internet and city directories to research newspapers and printing shops in each Utica.

8. a. The portrait of Wilson — which would’ve been hanging on the wall during and after his presidency — provides a rough time frame for this picture, as does the typewriter. We’d probably be able to get an exact date by finding out whose father is mentioned in the caption.

Scoring

Number of correct answers

6 to 8 Picture Perfect

4 to 5 Camera Conscious

2 to 3 Out of Focus

O to 1 Underexposed

ADVERTISEMENT