Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

In 3 Next Steps for Your DNA Test Results we shared tips for making use of your DNA. Looking for advice on how to apply DNA test results toward your own research? We’ve got you covered.

Applying These Strategies

I’ll show you what I mean by applying these three steps to a research question from my own family tree. Who is Otto Murhard, born around 1825 to 1830-ish in either Germany or South Carolina (census records disagree)? I know about him only from his presence in records about his daughter Josephine, who is my ancestor. Here’s how I used genetic genealogy to investigate:

First, I applied ethnicity results. The ethnicity results I used are my father’s, to eliminate unrelated results I’d have from my mom’s side. On my dad’s tree are lots of folks from Virginia, the northeastern and midwestern United States, some England, one Denmark and one Sweden. If the Murhards are from Germany, they’ll be the first Germans I’ve identified on my dad’s side.

Each of the DNA testing sites defines German ethnicity differently, both geographically and genetically. Why? Because their genetic data depends on the company’s particular reference populations, the group of people used to determine the genetic signature of an area. The company compares your DNA to its reference populations to determine your ethnic percentages.

23andMe, which lists German in its own ethnic category, says my dad is 9.3 percent French and German. AncestryDNA says he’s 42 percent Europe West. At Family Tree DNA, he’s 40 percent West and Central Europe. At MyHeritage DNA, he’s 88 percent North and West European. AncestryDNA assigns my dad to three Migrations, none specific to Germans. One of the Migrations, though, is specific to the southern United States.

What’s the take-home message here? Don’t rely on ethnicity results to direct your genealogy. Just use them as a clue when you can. In the case of Otto, they’re not helpful.

Comparing Match Surnames

Second, I looked at more-concrete genealogical information for my matches: surnames, locations and genetics. Otto is my dad’s great-great-grandfather, meaning that fellow descendants of Otto would be my dad’s third cousins. Matches who are descendants of Otto or his wife, Johanna’s, parents would be my dad’s fourth cousins. I search my match pages at each testing company by surname first, looking for any other Murhards. I found no matches for that surname at Family Tree DNA, MyHeritage DNA or 23andMe.

But at AncestryDNA, I found a fourth-cousin match who has a Murhard in her family tree. Let’s call this match Anne. From’s Anne’s tree, I can see she’s my dad’s second cousin, twice removed (abbreviated as 2C2R). That means they’re both descended from Otto, but there’s a two-generation difference between them. This brings up an important point about the difference between your genetic and your genealogical relationship. Their genetic relationship is fourth cousins: that is, they share approximately the same amount of DNA that typical fourth cousins share. But their genealogical relationship is 2C2R.

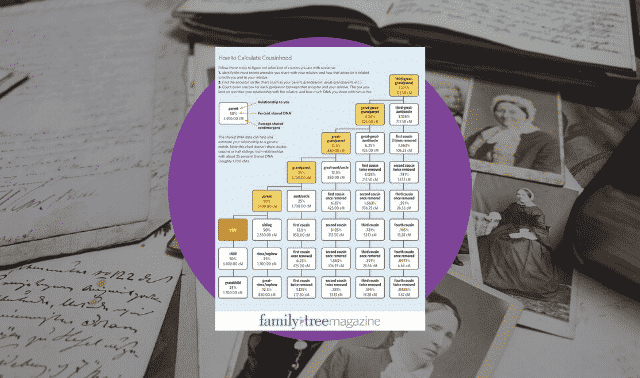

Once I found Anne and her Murhards, I explored her tree in detail. Sure enough, Anne lists Josephine, Otto’s daughter, as her ancestor. Then I needed to double-check that my genetic and genealogical relationships with Anne made sense. I clicked on the little “i” to see that she shared 61 cM of DNA with my dad. According to the aforementioned Shared cM Project chart, 2C2R share an average of 86 cM, with a range of 0-201 cM. So this match was in the right range. I definitely wanted to double-check the genealogical research that has led both Anne and me back to this ancestor.

Shared Matches

Unfortunately, Anne’s tree didn’t have any more information about Otto and Johanna than I already have (less, actually). But now that I had a confirmed match back to Otto, it was time to employ the Shared Matches tool to find others who might share ancestry with both me and Anne. Remember, Anne’s matches could be related to Josephine (and therefore Johanna and Otto) or to Josephine’s husband, who was a Butterfield.

The Shared Matches tool brought up 11 people, including two second cousins with small or nonexistent pedigrees, and five third cousins. Trees showed that several of the matches were descendants of my Josephine, but they didn’t come up in my surname searches because they spelled Murhard with a t: Murhardt. Note to self: the surname search in AncestryDNA isn’t nearly as forgiving as Ancestry’s record search is.

A fourth cousin, P.H., didn’t have a family tree posted. However, when I clicked on his name, I found he did have a tree associated with his Ancestry account—it just wasn’t linked to his DNA test. That tree contained an Otto Murhard. It appeared that Otto was P.H.’s great-great-grandfather through a daughter named Caroline. If this was same Otto as mine, P.H. and my dad should be third cousins. But they only shared 39 cM of DNA, an amount that’s much lower than (but not completely out of range for) the 79 cM that average third cousins share.

A check of locations indicated that P.H.’s Murhard relatives were all in Oregon, where my Josephine was born. So now I had a name connection, a place connection, and a genetic connection—albeit one not as strong as I might like.

What’s Next?

So what should my next step be? More genealogy research. I need to look for genealogical records that would connect my Josephine to P.H.’s Caroline. Were they sisters? I also could look for more genetic connections by exploring my Shared Matches with P.H. Unfortunately, most of those don’t have pedigrees. So I need to reach out to them and ask about their ancestors or encourage them to post trees online. The truth is, in genetic genealogy, you often spend time doing other people’s genealogy. And that’s okay.

As you can see, DNA testing hasn’t solved the mystery of Otto Murhard. But more—even better—matches may materialize on any one of my DNA dashboards any day. And meanwhile, thanks to these DNA matches and tools, I have more clues and confidence regarding my connection to Otto than when I started.

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2018 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT