Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

No matter where in the United States your research takes you, you’ll need to track down some key information about your ancestors and the records they appear in. These five genealogy facts common to all genealogists will save you time, money or both as you conduct your research.

1. Civil Registration Start Dates

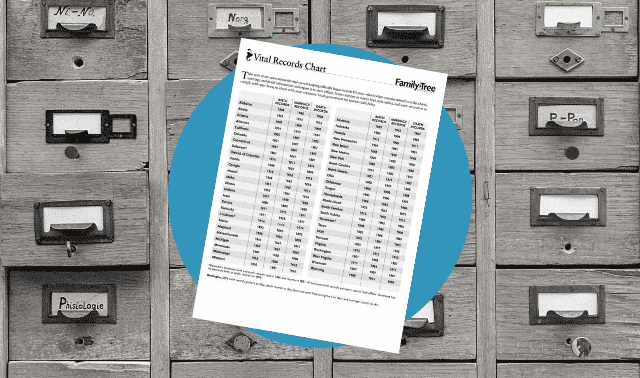

Genealogists consider vital records to be … well … vital to their research. And for good reason—vital records document your ancestors’ most important life events: birth, marriage and death. With civil registration, state governments systematically documented these critical events.

Unfortunately, US states began civil registration at different times, making a patchwork of US vital records. You can find this information in our state guides or in this handy downloadable chart.

State governments typically began recording births, marriages and deaths early in the 20th century, but start dates differed. Many towns in New England, for example, kept vital records much earlier, even into the 1600s. But New Mexico didn’t begin until 1920. And even when laws were in place, not all localities consistently complied.

Prior to civil registration, you’ll look for vital records primarily among church records.

2. Federal Census Availability and Questions

Which censuses will your ancestors appear in? What questions did each census ask? Have censuses from your ancestor’s time and place survived? How will your ancestor be listed?

Your answers to these questions will affect which databases to search and how likely you are to find your ancestors in them. Have all that information at the ready to maximize your research time.

Some key information about US censuses generally:

- The first US census was taken in 1790, but not every member of a household was named until the 1850 census. Find search strategies for early censuses here.

- Records are complete for most censuses in most places, with two notable exceptions: The 1890 census has been lost for most locations, and early census records (1790–1810) tend to have spottier coverage than others.

- Censuses have been taken every 10 years, but privacy laws restrict access to records of them. The most recent available to researchers is the 1950 census.

- States generally appear in the first census in which it was a state or territory. The original 13 US states have been in every count since 1790, but subsequent additions to the Union appeared later. Study territorial history to understand when and under which jurisdiction your ancestor’s hometown might have appeared in the census—it might be different from the state the town is in today.

- Many states and territories took their own censuses between or concurrent with federal counts.

3. Border Changes

Even if you know where your ancestor hails from, you may still have trouble discovering records of him. City and county boundaries shifted over time as municipalities merged or split. These changes affected what archives created your ancestors’ records—and where you can find them today.

Consult online resources like Randy Majors’ interactive Historical U.S. County Boundary Maps or the Newberry Library’s Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. Gazetteers can also help.

State and even country borders often changed, too. For those researching overseas, familiarize yourself with the history of the area you’re researching, as major conflicts likely resulted in border changes. Your ancestor’s town may also be known by different names in different languages.

4. Naming Traditions

Not sure how members of your family might be related? Many cultures used specific naming traditions that can help you determine who was related to whom.

For example, Irish families often named the first son after the father’s father, the second son after the mother’s father and the third son after the father. So if you know a couple named their first son Patrick, you can reasonably guess the man’s father was named Patrick as well.

You can find other naming clues such as patronymics that can hint at previous generations’ names. Also stay on the lookout for recurring given names, plus names that might have been “translated” from one language to another.

Knowing if and how your ancestor’s name changed over time (including how it might have been Americanized) can also help you find them in records. Study how first names changed across languages (John, Juán, Hans, and Jean, for example), and create a surname variant chart to track the myriad ways your ancestor’s name was spelled in records.

5. Levels of Cousinhood

We all know how parents are related to their children. But what relative do you share with a third cousin twice removed? To understand your research (particularly DNA results), you’ll need to understand the different levels of cousinhood.

Fortunately, we have a cousin comparison chart that will help you figure out how you relate to even distant cousins. You’ll need to know what ancestor you and your relative share in common, and how you are each related to them.

For example, say your great-great-grandfather is your relative’s great-great-great-great-grandfather. As the chart indicates, you are third cousins because your common relative is a great-great-grandparent. But you’re “twice removed” because there’s a two-generation difference in how you and your relative are related to that ancestor. Therefore, you and your relative are third cousins twice removed.

Last updated, February 2024

ADVERTISEMENT