Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

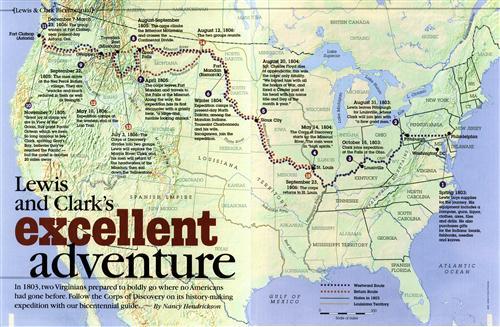

Two hundred years ago — long before Gore-Tex, GPS and modern mountain climbing gear — two Army officers from Virginia were gearing up for the ultimate wilderness adventure: the original crosscountry road trip. The United States had just negotiated the Louisiana Purchase, a bargain transaction that allowed the young country to double its size for only three cents an acre. More important than price, however, was the opportunity to explore the western half of the continent.

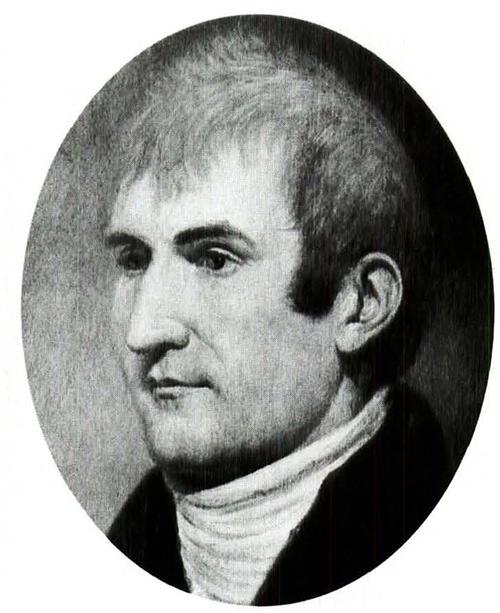

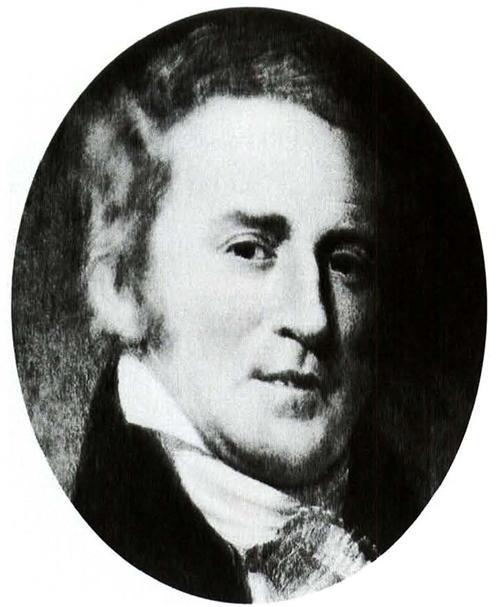

Meriwether Lewis, William Clark

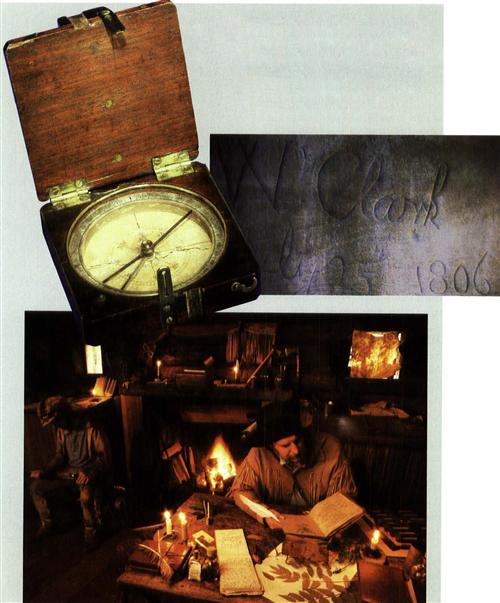

At President Thomas Jefferson’s behest, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were about to do just that, using inaccurate maps, a basic compass and other tools of early 19th-century technology. In 1803, America’s knowledge about the West derived mostly from the imagination. But Jefferson intended to change that: Even before he sealed the Louisiana Territory deal, he’d secretly planned for an overland expedition to the Pacific. He appointed Lewis, his private secretary, to head the expedition. Lewis invited his old friend and Army buddy Clark to be his co-leader. The Corps of Discovery was born — and two centuries later, Lewis and Clark’s adventuresome spirit still shapes America’s identity.

Jefferson got the corps rolling with $2,500 in congressional funding — enough to pick up guns, ammunition, medicine, mathematical instruments, camp supplies and presents for the Indians. Before the three-year journey was over, the total cost ran close to $40,000.

The president’s instructions to the young Virginians were explicit: They were to find “the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.” In other words, the mythical Northwest Passage that explorers since Columbus had been itching to discover.

They also were to take latitude and longitude readings at “all remarkable points” between the mouth of the Missouri River and the Pacific coast, and make several copies of their observations. Jefferson told them to put copies “into the care of the most trust-worthy of your attendants, to guard… against the accidental losses to which they will be exposed.” The resultant journals were more than he could have anticipated.

For nearly a thousand days, Lewis, Clark and their band of 30-odd men, one Indian woman and her baby explored the vast regions of a newly acquired territory. They traded with Indians, fought grizzlies, struggled through bitter cold and heat, and crossed some of America’s most rugged terrain. Along the way, Lewis was wounded in the backside by French fiddler Pierre Cruzatte, who mistook him for an elk. But the corps’ only fatality was Sgt. Charles Floyd, who died of appendicitis.

In all, Jefferson’s Corps of Discovery traveled more than 8,000 miles. Because the men’s journals are exact and their mapping accurate, today it’s possible to follow their route closely. And during the next few years, you can join tens of thousands of adventurous Americans who are expected to do just that.

The bicentennial hoopla has begun already, as states along Lewis and Clark’s trail gear up for your visit. At the North Dakota Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center in Washburn <www.fortmandan.com/lewisclark.html>, for example, you can view exhibits, try on a buffalo robe, wear a cradleboard much like Sacagawea’s and marvel at the immensity of a dugout cottonwood canoe — the corps hand-carved 15 such canoes on its journey. Plus, you can stock up on supplies for your own expedition: books, music, videos and more.

You also can participate in 15 National Signature Events (and hundreds of local celebrations) planned between January 2003 and fall 2006. Coordinated by the National Council of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial <www.lewisandclark200.org>, the events officially kicked off Jan.18 at Monticello, Jefferson’s Virginia home. Clarksville, Ind., and Louisville, Ky., will host the second signature event, beginning Oct. 14 — the day Lewis met up with Clark at the Falls of the Ohio, which the two cities border. Look for Corps of Discovery II, a traveling museum and classroom, which ultimately will visit more than 400 communities in 19 states along the Lewis and Clark Trail. The Falls of the Ohio celebration will conclude Oct. 26, 2003, with the re-enactment of the corps’ 1803 departure from Clarksville.

The bicentennial will offer plenty more opportunities for historical exploration. So pack up the car and join the nation as it celebrates 200 years of unparalleled discovery.

“All in health and readiness to set out. Boats and everything Complete, with the necessary stores of provisions & such articles of merchandize as we thought ourselves authorised to procure — tho’ not as much as I think nessy.”

— William Clark, May 13, 1803

The road to discovery:

Illinois, Missouri, Kansas and Nebraska

From 1803 until spring 1804, preparations were made for the journey. With instructions from astronomer Andrew Ellicott and mathematician Robert Patterson, Lewis learned to compute longitude through lunar observations. Benjamin Rush, a leading physician, gave him a crash course in medicine.

On June 19, 1803, Lewis wrote to Clark, asking him to join the adventure. Clark wrote back: “No man lives whith whome I would perfur to undertake Such a Trip &c. as yur self.”

The leaders purchased supplies and filled the roster with men who (Lewis hoped) were “stout, healthy, unmarried … accustomed to the woods, and capable of bearing bodily fatigue in a pretty considerable degree.” On May 14, 1804, their famed voyage up the Missouri River began.

You can begin your own voyage along the explorers’ trail in May 2004 in Hartford and Wood River, Ill. To commemorate Lewis and Clark’s departure from their winter camp, the communities will host send-off ceremonies, re-enactments and heritage craft and skill demonstrations.

A replica of Lewis and Clark’s keelboat will arrive in Saint Charles, Mo., May 15, launching a weeklong gala with more than 25 fife-and-drum corps and military units from all over America. Experience a re-enactment of the corps’ encampment, period food, authentically dressed re-enactors and booths featuring 19th-century crafts.

On the Fourth of July, the river communities of Fort Leavenworth and Atchison, Kan., along with Kansas City, Mo., will commemorate the first July 4 ever celebrated in the West. Then drive to Fort Atkinson State Historical Park in Nebraska, where a dramatic re-enactment of the expedition’s first meeting with the Otoe and Missouria tribes takes place July 31-Aug. 3.

Indian encounters:

South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana and Idaho

The expedition arrived in present-day North Dakota in October 1804 and wintered at Fort Mandan. There, they met Sacagawea, the Shoshone who had been kidnapped as a child by the Hidatsa and sold to French Canadian trader Toussaint Charbonneau. And Sheheke, leader of the Mandan earth-lodge village near Fort Mandan, befriended them. The Mandan took an interest in Clark’s black slave, York. “Those Indians wer much astonished at my Servent, they never Saw a black man before,” wrote Clark. “All flocked around him & examind him from top to toe, he Carried on the joke and made himself more turribal than we wished him to doe.”

That winter, as game grew scarce, the Mandan and Hidatsa traded corn to the explorers for metal tools and weapons. Pvt. John Shields built a forge near Fort Mandan, where he pounded “Missouri war axes” from the remains of a sheet-iron stove that had given out on the trip north. He and his helpers also repaired hoes, axes and guns. The exchange rate: eight gallons of corn for a four-inch square of iron.

A 10-day event called Circles of Culture, Time of Renewal & Change will commemorate this cooperation between the native inhabitants and the expedition. Visitors can taste, see and hear much of what Lewis and Clark experienced at the winter camp. The event will take place Oct. 22-31, 2004, in and around Bismarck, ND.

The Corps of Discovery celebrated its second Fourth of July, in 1805, with dancing and whiskey drinking at the Great Falls of the Missouri. Beginning June 2, 2005, visitors to Great Falls, Mont., can join in 33 days of fun and festivity. Take your pick of river float trips, tours, re-enactments, Indian games and symposiums. The town’s planning a spectacular July 4 fireworks display, plus a community picnic serving up Lewis and Clark grub.

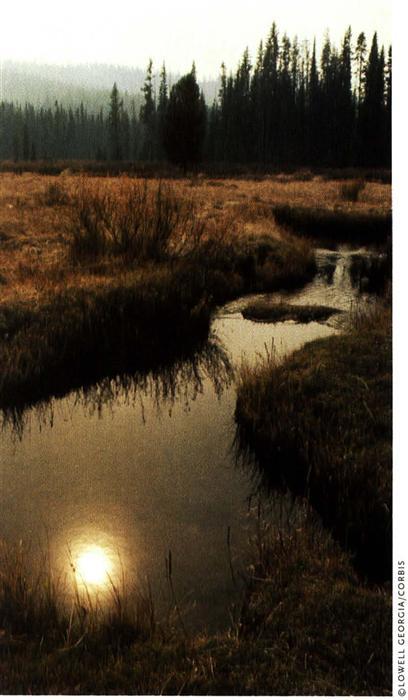

The next months of the corps’ journey brought less celebration. An August scouting trip led Lewis to Lemhi Pass, on the Montana-Idaho border. The view from this perch wasn’t what Lewis had expected: Instead of a great river flowing to the Pacific — the storied Northwest Passage — he spied only endless mountaintops.

Lewis, Clark and crew crossed the Bitterroot Mountains in September. The men’s disdain for the rugged terrain is apparent from their journal entries: Clark described the Bitterroots as “high ruged mountains in every direction as far as I could see.” Expedition member Patrick Gass called them “the most terrible-mountains I ever beheld.” True to Gass’ words, the crossing would be one of the expedition’s toughest tests. When they arrived in Idaho — weak and nearly starved — Indians again came to their aid: The Nez Percé, having decided to befriend their “conquerors,” shared food and trade secrets (namely, how to hollow out a canoe with fire instead of tedious digging).

If you crave sights of the wilderness as Lewis and Clark witnessed it, Idaho boasts the most pristine section of their trail. The expansive view from Lemhi Pass has changed little in two centuries. In nearby Salmon, Idaho, you can expand your view of Sacagawea and her Shoshone people at a new interpretive center named in her honor, opening in May.

Pacific explorations:

Washington and Oregon

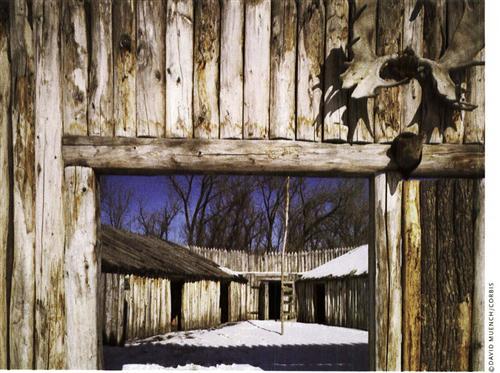

Journal accounts say the winter of 1805-1806, which the men spent at Fort Clatsop in present-day Oregon, was miserable. The men endured bad food, rain and homesickness. They’d been gone nearly two years.

They temporarily relieved their boredom in January with an excursion to see the remains of a beached whale. Sacagawea wanted to see the whale, too. “The Indian woman was very impo[r]tunate to be permited to go, and was therefore indulged,” Lewis wrote. “She observed that she had traveled a long way with us to see the great waters, and that now that monstrous fish was also to be seen, she thought it very hard she could not be permitted to see either (she had never yet been to the Ocean).”

Although Lewis and Clark were eager to leave Fort Clatsop, they used the winter stay to catch up on their journal entries. Lewis wrote extensively about the plants, animals and natives encountered on the Pacific side of the Continental Divide. Clark drew maps of the route they’d taken since leaving Fort Mandan. The men also replaced their tattered clothing — by their spring departure, they had made 338 new pairs of moccasins.

“We Suffered the party to fire off their pieces as a Salute to the Town. We were met by all the village and received a harty welcom from it’s inhabitants &c.”

— William Clark, upon returning to St. Louis Sept. 23, 1806

End of an epic journey

In summer and fall 2006, other signature events — many still in the planning stages — will commemorate Lewis and Clark’s long journey home. One of those celebrations is a July 25 ceremony at Pompey’s Pillar, near Billings, Mont.

The Crow Indians called this sandstone column “Place Where the Mountain Lion Dwells.” Clark renamed it to honor Sacagawea’s son, nicknamed Pomp. On the column, Clark left the only remaining physical clue to the expedition’s presence on the trail: “I marked my name and the day of the month and year.” You can still see where Clark carved his signature into the soft stone.

The ceremony will focus on Clark’s journey down the Yellowstone River and his arrival at Pompey’s Pillar. Visitors will be able to explore a new interpretive center and take part in river floats, historical re-enactments and American Indian games.

Other events will commemorate the corps’ return to the Mandan village in North Dakota and their travels through Idaho. The final celebration will commence in St. Louis, where the expedition ended Sept. 23, 1806. The explorers greeted the city with a gunshot salute.

Now it’s time for you to salute these men’s tenacity and courage. Pick up a copy of their journals, pull out your road atlas and plan your own voyage of discovery. The landscape may have changed, but the journey’s significance hasn’t. As Jefferson put it, “Messrs. Lewis and Clarke and their brave companions, have, by this arduos service, deserved well of their country.”

From Family Tree Magazine’s March 2003 America’s Scrapbook.

ADVERTISEMENT