Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

I grew up in a Blue-Gray household. When watching movies or playing war games about what my Alabama-born mother called “the War Between the States,” my youthful sympathies were nonetheless solidly with the Union. Only later, doing genealogy research as an adult, did I discover that my Illinois ancestors arrived from Sweden much too late to don any color and that my lone Civil War ancestor wore gray: My great-grandfather William “Frank” Dickinson served with the 37th Alabama Infantry. Now that I’ve gotten copies of his military service records, I have a greater empathy for what both sides endured in “the recent unpleasantness.”

Nearly a century and a half since that great conflict – 2011 will mark its sesquicentennial – it’s never been easier to start researching your Blue or Gray soldier ancestor. Not only can you search for the basic facts of his military service, you also can delve into the details of his regiment and battles he may have fought in, trace the unit’s movements on historical maps, and perhaps even find an image of him with his comrades. Pension files and other records could provide long-sought details about your soldier’s spouse and children, helping you win your own battle to understand your family’s past.

The Civil War produced voluminous documents about the more than 3.5 million men (and a few hundred women) who fought both for the Union and the Confederacy. But because military records don’t fit the familiar patterns of most genealogical research – vital records, wills, passenger lists and the like – they can seem daunting to a first-time researcher. Fortunately, understanding a few key facts and a handful of essential resources can unlock a wealth of information about your Civil War ancestor. Follow these nine simple steps and you’ll soon be immersed in the epic struggle of North and South – and your ancestor’s role in that drama.

1. Look in the index.

First, you want to confirm your ancestor was in the war and learn some basic facts about his service. The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System (CWSS) — a massive project by the National Park Service with the Genealogical Society of Utah and the Federation of Genealogical Societies — puts basic information on 6.3 million soldier names just a click away. How can there be 6.3 million records in this online index, you ask, when only 3.5 million fought in the Civil War? If a solder served in more than one regiment, he’ll be listed multiple times; the same goes for men who served under more than one name or whose records are separated by spelling variations.

The CWSS contains transcribed information from General Index Cards, which were created beginning in the 1880s by Gen. Fred C. Ainsworth’s staff to determine veterans’ eligibility for military pensions. Happily, the staff pored over Confederate records as well, even though “Rebel” soldiers weren’t eligible to draw federal pensions. The names on the index cards were drawn from muster rolls, usually kept on the company level and updated about every two weeks. The original cards are now at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC.

Searching the CWSS couldn’t be easier. Click on Soldiers, then fill in as many blanks in the search form as you can: last name, first name, Union or Confederate, state or place of origin, unit, function (infantry, cavalry, artillery, sharpshooters or engineers). Don’t worry – you don’t have to know your ancestor’s unit; in fact, that’s one of the key pieces of data you can learn from CWSS. If you know the unit but can’t find your soldier, click on Regiments to search for a specific unit. You’ll get a brief regimental history and a link to a list of all soldiers in that unit.

A successful search will confirm your ancestor served in the Civil War and retrieve his name (as listed in related records), side (Union or Confederate), regiment and company, initial rank and final rank, and the microfilm location of the original index card. The index also might contain an alternate name or notes. You can find the same information on microfilm or in two series edited by Janet B. Hewett, both from Broadfoot Publishing: The Roster of Union Soldiers, 1861-1865 (33 volumes) and The Roster of Confederate Soldiers, 1861-1865 (16 volumes).

You face a bigger challenge for sailor ancestors. Naval records aren’t microfilmed or well-organized for either side. To date, only the records of 18,000 African-American Union sailors are indexed in CWSS.

2. Go on record.

Now you’re ready to get a copy of your ancestor’s Compiled Military Service Record (CMSR).Every soldier has a CMSR for each regiment he served in, so if your ancestor was in more than one, seek out all his CMSRs. The CMSR envelope, with contents compiled from original muster rolls and other records, contains various cards typically recording whether the soldier was present during a period of time, facts of enlistment and discharge, and any wounds or hospitalization. (Note you usually can’t prove from a CMSR that a soldier was present in a particular battle, unless he was injured or captured.) His place of birth may be noted; only the country is listed for foreign-born men. The CMSR also may include an internal jacket of “personal papers,” such as his enlistment documents and any prisoner of war records. According to NARA’s Civil War records guide, CMSRs “were so carefully prepared that it is rarely necessary to consult the original muster rolls and other records from which they were made.”

What might you learn from an ancestor’s CMSR? NARA’s guide gives the example of Pvt. William P. Western, Company D, 106th New York Infantry: He enlisted July 29, 1862, at DeKalb, NY. He was 26 years old, born in Stockholm, NY, and stood 5 feet, 8 inches, with gray eyes and brown hair. The CMSR follows Western as he was taken prisoner at Fairmont, Va., April 29, 1863. After his parole, Western suffered “remittant fever” and “chronic diarrhea” (perhaps more than you really want to know about an ancestor!), and was hospitalized in Virginia and Washington, DC. During his service, he received $95 in clothing, $27 in advanced bounty and pay through Aug. 31, 1864; he owed $1.27 for a “painted blanket” and $23.96 for transportation.

Confederate records tend to be sparser and less detailed, though some CMSRs from Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama units list battles the soldier fought. Most Union CMSR files aren’t microfilmed, but you can access microfilmed Confederate records at NARA or the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL). Study original Union or Confederate CMSRs at NARA in Washington, DC, or request copies: On the Web, go to Order Online and click Made-to-order Reproductions. To get copies by mail, use NATF Form 86, which you can request by using the Contact Us form on the National Archives website. Compiled Military Service Files cost $30.

If you learn your ancestor, like Western, was a prisoner of war, check Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, 1861-1865, on NARA or FHL microfilm. On CWSS, click Prisoners to search its index of Confederate prisoners held at Fort McHenry and Union prisoners at Andersonville.

3. Draw on pensions.

If your ancestor fought for the Union, it’s likely he, his widow or his minor children later applied for a pension. Surprisingly, these pension files often contain richer information about a soldier’s service than his CMSR does, including a medical history if he lived for a number of years after the war. Pension files can be a genealogical gold mine for researching the family, too: Widows had to supply evidence of marriage, and applicants on behalf of minor children had to prove their birth and the soldier’s marriage. Western’s pension file, for example, details his death and burial in October 1864, his marriage to Ulisa Daniels; the birth of their daughter, Rosena; and Ulisa’s remarriage to Patrick Curn.

Union pension records are indexed on 544 rolls of NARA microfilm called General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934 (T288),which also are available from the FHL. The index is arranged by place, then by the veteran’s or widow’s name. You can also search it online at Ancestry.com ($189 per year) or free at libraries offering Ancestry Library Edition. You can also use Fold3 to search for transcribed information. Some collections may be free to use with a basic account; others may require a Premium Membership, which costs $79.95 per year or $7.95 per month. You can sign up for a free 7-day trial.

The actual pension files aren’t microfilmed, but you can request copies from NARA’s Order Online service or by mail using NATF Form 85. Ask for copies of all the documents in the file, or you’ll get only selected pages. If you order online, you can choose either the Pension Documents Packet for $14.75 or the Complete File for $37 (again, NARA price increases might’ve taken effect by the time you read this).

The victorious federal government wasn’t too eager to pay pensions to those who’d fought against it, so Confederate pensions fell to the states. Some paid only to indigent or disabled veterans, widows and orphans. A qualifying veteran could apply to the state where he lived, even if he served in another state’s unit. NARA doesn’t keep Confederate pension records, but does provide a guide to locating them. Most Confederate pension files are on FHL microfilm, and several states have put indexes or applications online.

Many former Confederate states also built soldiers homes for needy veterans. Records of homes in Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Missouri, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia are available on FHL microfilm — run a keyword search of the online catalog on the state name and soldiers home. You also can search online indexes to homes in Arkansas and Tennessee.

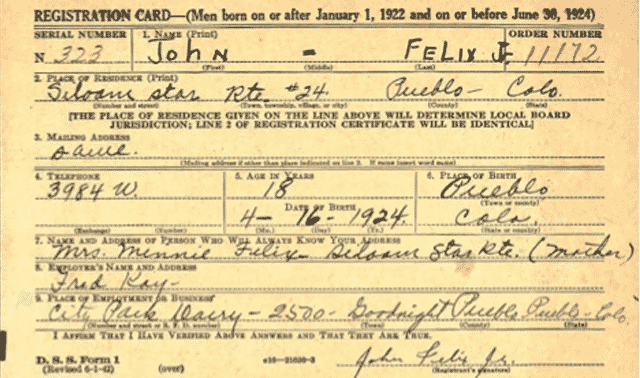

4. Draft your ancestors.

Not all Union soldiers were volunteers, of course. In 1863, Congress enacted the nation’s first military draft; it applied to men ages 20 to 45. Draft records, which aren’t microfilmed, are at NARA in record group 110, Records of the Provost Marshal General’s Bureau. They include much genealogical data, even if your ancestor never actually served. Consolidated Lists show each man’s name, residence, age, occupation, marital status, place of birth and any previous military service. Descriptive Rolls include physical description, birthplace and whether the person was enlisted. Both listings are organized by state, then congressional district, then surname. To find your ancestral county’s 1863 congressional district, consult United States Congress, Congressional Directory for the Second Session of the Thirty-Eighth Congress of the United States of America, available on FHL film 1425543 (Item 6, Official Congressional Directory).

The Enrollment Act of 1863 granted your Union ancestor the option to avoid military service by giving a substitute $300, but in practice, this fee escalated. With a little digging in draft records, you can find out if your ancestor followed the example of, for instance, then-future president Grover Cleveland, who paid 32-year-old Polish immigrant George Beniski to take his place in the 76th New York Infantry.

If you’ve already found your ancestor’s CMSR and pension files, there’s little extra to be gleaned from draft records. But if you strike out in the former, draft records may provide otherwise-elusive answers.

5. Enlist the census.

Yes, those decennial head counts so familiar to family tree researchers sometimes hold clues about Civil War service. The 1890 census included a special enumeration of Union veterans and widows. Most of that census was lost to fire, but those special schedules survived for states alphabetically from Kentucky through Wyoming. You can access census records on FHL and NARA microfilm, and on Ancestry.com.

The 1910 census also asked whether a person was a survivor of the Union Army (abbreviated UA) or Navy (UN), or the Confederate Army (CA) or Navy (CN). Some postwar state censuses, such as the 1865 New York and 1885 Wisconsin enumerations, also identified Union veterans (both of those state censuses are on FHL microfilm; veterans from the latter one are in a digitized book at Wisconsin History. Several Southern states took censuses of Confederate veterans. Those available on FHL microfilm include Alabama in 1907, 1921 and 1927; Arkansas in 1911; and Louisiana in 1911.

6. Join the club.

After the war, many Union veterans joined organizations such as the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) – by 1890, some 40 percent of Union veterans were GAR members. The records of local GAR posts, including rosters and meeting minutes, often provide genealogical information about members. Look for them in state historical societies, archives and libraries. They’re on FHL microfilm for some states, including Iowa, South Dakota, Michigan, Nebraska, Oregon and Utah. See a listing of GAR posts by state on the Library of Congress website.

Union officers formed the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, which exists today as a hereditary group. Other hereditary organizations include the Daughters of Union Veterans of the Civil War and the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War; both offer historical information on their Web sites.

Confederate veterans established the United Confederate Veterans in 1889. Records of the organization are available on FHL microfilm, and the Library of Virginia has an online index to names in Confederate Veteran magazine. Confederate hereditary groups include Sons of Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy.

7. Visit the cemetery.

Whether it happened during the war or years later, all Civil War veterans have passed on-and cemetery records yield more ancestral clues. About 200,000 Union soldiers who died in the war are recorded in the 27-volume Roll of Honor, available on FHL microfilm and on CD (Genealogical Publishing Co.). It’s arranged by burial place, so first check Index to the Roll of Honor by Martha and William Reamy and its addendum, The Unpublished Roll of Honor by Mark Hughes, both from Genealogical Publishing Co.

If you think your Civil War ancestor is buried in a government cemetery, start your search at the Department of Veterans Affairs’ National Gravesite Locator. This site indexes burial locations of veterans and their families in VA national cemeteries, state veterans cemeteries and other military and Department of Interior cemeteries.

An 1879 act of Congress authorized the government to provide headstones to soldiers and veterans buried in private cemeteries. The cards recording these 166,000 headstones – honoring Union soldiers and veterans who died between 1861 and about 1903 – are on NARA microfilm M1845; the FHL has copies. You’ll get the name, rank, company and regiment, date of death, place of burial and grave number, if any.

No single source lists all the 250,000 some Confederate soldiers who died during the Civil War, but the FHL has several useful references. Two book series compiled by Raymond W. Watkins are good starting places: Confederate Burials (28 volumes) and Deaths of Confederate Soldiers in Confederate Hospitals (15 volumes).

CWSS eventually will contain an index to all the burials in the National Park Service’s 14 national cemeteries. To date, find data and headstone images only from Virginia’s Poplar Grove National Cemetery at Petersburg.

8. Follow the regiment.

Once you’ve researched your ancestor’s military records, you can learn much more about his Civil War experiences by studying his regiment and company. For a quick regimental history, including major battles, just click on the CWSS site’s Regiments link. It covers 4,000 Union and Confederate units, with links to soldiers’ names and detailed battle histories. Also look for books about your ancestor’s regiment on the Library of Congress website.

The ultimate information source for Civil War events — though it rarely names individual soldiers — is the “OR.” That’s the War Department’s 70-volume The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Many large public and university libraries have these books, which also are on NARA and FHL microfilm. Even better, you’ll find a searchable version of the OR at the Cornell University Library (click Browse, then look under Multivolume Monographs). It’s also available through Ohio State University’s History website.

You’ll also want to consult the unit histories in Supplement to the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies compiled by Janet B. Hewett (51 volumes, Broadfoot Publishing). It’s drawn from two NARA regimental records microfilm collections: the 225-roll Compiled Records Showing Service of Military Units in Volunteer Union Organizations and its 74-roll Confederate counterpart.

For additional background on the war, see if your library subscribes to the new Civil War Era database from ProQuest Information and Learning. The service includes complete runs of eight newspapers from the North, South and border states spanning 1840 to 1865, as well as nearly 2,000 opinion pamphlets from leaders of the era.

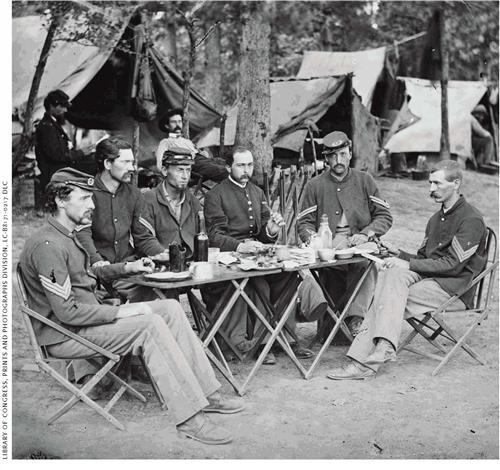

9. Use visual aids.

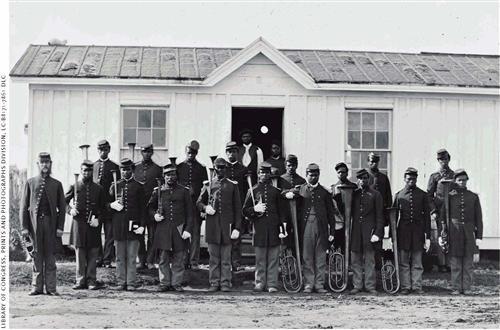

Nothing brings your ancestors’ world alive like images. Photographers such as the legendary Mathew Brady made the Civil War the first military conflict captured in pictures, showing uniforms, weapons, camp life and battle aftermath. Maps let you trace the movements and battlefield positions of your soldier’s unit. NARA offers a guide to its Civil War images, including maps and Brady’s work. Access the archive’s war-related holdings through its Archival Research Catalog. The Library of Congress’ American Memory site offers digitized Civil War maps and photos from its own and other repositories’ collections; browse or search from the Library of Congress’ American Memory: Remaining Collections. The Library of Congress Prints & Photograph Division offers photographic holdings. Another key resource for photos and maps is the US Army Heritage and Education Center in Carlisle, Pa.

Whatever you learn about your ancestor’s part in the great drama of the Civil War-whether he turns out to be a Yankee or a Rebel, a hero or a deserter — finding how your family fits into this American epic will illuminate that time, almost 150 years ago, as no schoolbook lesson can. When the Civil War sesquicentennial hoopla begins, you can say,“We were there.”

From the July 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine

Updated: May 2022

ADVERTISEMENT