Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

What’s old, made of glass and found in a photographic case? If you answered “an ambrotype,” congratulate yourself on your knowledge of photo history. Unlike the innovative daguerreotype and the widely popular tintype, ambrotypes are misunderstood and often confused with other cased photographs. It’s time to give them their due.

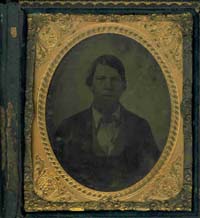

Debra Fleming found this image in a etched box with a latch on the side. It once belonged to her mother-in-law. While she recognized it as a photograph, she was puzzled by the case and the fact she could see through the image. She had two problems: identifying the person pictured and the photographic method. The latter was easy.

In July 1854, Bostonian James Cutting patented the process of applying photo-sensitive chemicals to glass and named it the ambrotype. Just like a daguerreotype, ambrotypes consist of the image, a mat and a cover glass. Ambrotypes are unique, however, because they’re actually glass negatives backed with a dark cloth, varnish or paper that gives the appearance of a positive. Deterioration of the backing is a common problem—as it flakes off or separates, the image becomes transparent.

Photographers produced ambrotypes in daguerreotype sizes so they could use the same cases, but later in the 1850s, they switched to special cases that could accommodate the extra thickness of the glass negative.

Ambrotypes reached peak popularity in the mid-1850s and quickly fell out of favor in the early 1860s. Dating these images relies on the case design and construction and the design of the mat, photographic details such as the clothing, and family data. Fleming’s box is a molded paper case with an embossed design. Elaborate mats like this one were common in the late 1850s and into the 1860s. This man’s shawl-collar vest, wide tie and hair over the ears suggests a date in the late 1850s.

Fleming wants to know if this image depicts Thomas Winn Fleming (1815-1894), his son Thomas Madison Fleming (1845-1888), Robert Russell Evans (1817-1865) or John Hatcher McMath (1809-1857). My biggest question about this picture is, “Does this man look like he’s in his 40s?” That’s how old he’d be if he were the elder Fleming or Evans. I think he looks to be in his late 20s or early 30s. I can rule out McMath because he’d be too old to be this man, and Thomas Madison Fleming would be too young.

In order to really solve this mystery, I’d try to locate pictures of the other men. The older Fleming served in the Georgia senate and was a well-known planter before the Civil War, so contacting the Georgia Historical Society, might result in other images. Evans was a Methodist Minister in Thomasville, Fla.; the local public library might be able to help locate photo resources.

If no additional portraits are available, Fleming can compare his facial features—he has wide cheekbones, a full mouth and a broad-tipped nose—to other men in the family to narrow the picture to one branch. <!–

Watch for props. –><!–

2000–>

ADVERTISEMENT