Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Change is a platform political candidates often use when they want to distinguish themselves from the status quo. Change can be scary, but proposing a different approach often pays off, as it did for then-presidential candidate Barack Obama in 2008.

A new approach can be good for your genealogical research, too. Newspapers are frequently an unexplored genealogical frontier. They bring to mind endless hours of scrolling unindexed microfilm, and African-American researchers may believe newspapers didn’t pay attention to their relatives.

But guess what? Newspapers hold much promise for those seeking to navigate the somewhat choppy waters of African-American research. With the exponential rise of the black press following the Civil War, newspapers such as the Florida Tattler, Chicago Defender and Kansas City Advocate became a major repository of the experiences, hopes and dreams of former slaves and their succeeding generations. And with a recent surge in digitization projects and newspaper websites, these chronicles are more accessible than ever before. (See Getting Into the News below for help finding African-American newspapers that may hold your ancestor answers.)

So whether you’re conducting research in a red state or a blue state, switching up your research routine to include African-American newspaper resources is a change you can—and should—endorse. Here are 11 ways African-American newspapers can advance your search for your black roots.

1. Establishing pre-Civil War status

Were your ancestors slaves, or were they free prior to 1861? (By 1860, the United States was home to about a half-million free African-Americans.) Many of us lack the documentary evidence or oral history needed to answer this pivotal question. What we can definitively attest to is the cruelty of slavery in its reckless disregard for the family unit. In addition, the chaos of war added to separations as enslaved individuals dashed for freedom when Union military units passed through.

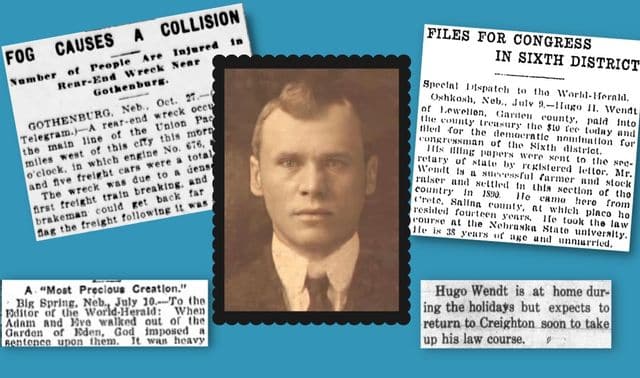

As a result, family members sought lost kinfolk for decades following the war. Advertisements from former slaves seeking loved ones can be found throughout the pages of many newspapers. If you find your ancestor’s name in one, it should indicate whether he was a slave. Death notices, sometimes consisting of just a few sentences, also often reveal evidence of prior enslavement. This is especially true in the case of elderly community members, and you’ll frequently encounter standalone articles with “former slave” or “ex-slave” in the title.

2. Finding pre-vital records death details

Early newspapers routinely carried news of individuals’ deaths within their pages, regardless of the person’s lot in life. In many instances, this is the only surviving documentation of the event. Search papers for a few weeks before and after the death date—you might find references to an illness preceding the death, or funeral services may have been postponed until distant relatives could arrive.

For average citizens, papers generally covered locals who resided in town or the surrounding rural community. Geography wasn’t a factor, though, when decedents met with fates other than natural causes, such as murders, suicides or car-train accidents. News was hard to come by in the days before black newspapers had access to wire services, and many editors purchased subscriptions to other newspapers, black and white, for the express purpose of reprinting news.

Remember the columns in the 1900 and 1910 censuses that ask mothers how many children they’ve had and how many are living? How many times have you looked at the difference and wondered about those kids? A newspaper might explain what happened.

3. Making military service connections

Finding out whether an ancestor served in the military is important because it can lead you to the genealogical information contained in personnel files and other records. News columns identified former soldiers as they participated in veterans organizations, and in death these groups may be listed as taking part in burial ceremonies. If you suspect WWI service, search listings of men drafted during the war, which usually made front-page news. And the community news sections, also referred to as social columns, were filled with talk of departures to boot camp, arrivals home on leave and shipments overseas. Finally, be on the lookout for newspaper columns devoted to the activities of African-Americans in and around active military posts, soldiers homes and veteran organizations.

4. Opening a window on the community

Social columns were an essential part of black newspapers. Whether your ancestor lived in a village of a few dozen African-Americans or in a bustling city such as Cleveland, chances are good that community events found their way into print. Newspapers with national circulation aggressively sought local correspondents to collect news and sell subscriptions in hopes of boosting readership.

Social columns are full of news of births, deaths, marriages, sickness, accidents, out-of-town trips, visitors to the town and more. If you had ancestors in Indianapolis in 1902, they may have been in the crowd that the Jan. 11 Freeman reported was at the railroad station hoping to catch a glimpse of Booker T. Washington on his way to Decatur, Ill.

A few years ago, I compiled a list of more than 5,000 social columns covering communities in 46 states, the District of Columbia, Indian Territory, Mexico and Canada. You can search it by location or download a PDF organized by state at www.blackcoalminerheritage.net. Each listing shows the town the column covers, the newspaper it appeared in, and the date of the paper.

5. Providing pictures

In genealogy, pictures aren’t merely worth a thousand words—they’re priceless. From Pullman porters (see No. 7) to banana cart vendors, images abound in black newspapers. And you’ll find not only headshots, but wonderful group pictures like that of fire department Engine Co. 8 of Louisville, Ky. (from the March 8, 1924, Chicago Defender) and the wait staff of the Knutsford Hotel in Salt Lake City (in the Jan. 6, 1906, Indianapolis Freeman).

6. Determining church affiliation

Religion has always been central to the African-American experience. Although I have a good friend who’s chasing her Catholic roots in Chicago and Milwaukee, the overwhelming majority of our black ancestors were either Baptist or African Methodist Episcopal (AME). You’ll find churches of those affiliations in practically every community. In Champaign, Ill., for example, the two main black churches were Bethel AME and Salem Baptist.

If you can establish the religious affiliation of your ancestors, and then a specific church, you’ve opened an exciting and valuable avenue of research. Social columns often can provide this critical information. You’ll also find many newspapers carrying church-related articles, such as those on state and national church conventions, throughout their issues. In my experience using African-American newspapers, I’ve been pleasantly surprised to find women dominating much of the church-related news.

7. Detailing Pullman porters

Shortly after the Civil War, industrialist George Pullman began seeking former slaves to work as porters on his railroad sleeper cars. Over the years, renowned men such as Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall, author Malcolm X and Oscar “Doc” Joyner (grandfather of radio host Tom Joyner) joined their ranks. How many of you wish you had a Pullman porter in your ancestry? Finding one of these cultural icons on a family tree would make any genealogist justifiably proud.

Newspapers provide genealogists with resources to discover or verify a Pullman porter ancestor. The Chicago Defender and California Eagle are two papers that included columns for railroad employees. The columns are full of news related to the activities and routes of Pullman porters, and provide plenty of research clues. Last year while searching for Pullman porters in Ohio, I found a wonderful array of articles on dozens of these men, including a picture of Edward F. Smith of Cincinnati, a Tuskegee graduate who was an aviator in his spare time, in the July 29, 1928, Chicago Defender.

8. Unveiling entrepreneurs

One of the most surprising aspects of my experience using black newspapers has been discovering an amazing amount of material related to self-employed individuals. So check those census sheets and other documents carefully for signs of an entrepreneurial spirit among your ancestors. And be aware that your ancestor could have worked full time at a factory and operated a bicycle repair shop on the side.

Your ancestor’s business might be mentioned in an article, or he may have advertised in the paper. “A typical paper contained numerous small advertisements of groceries, meat markets, restaurants, boarding houses, dressmakers, employment agencies, and notices of Negro lawyers and physicians,” states noted historian Emma Lou Thornbrough in a 1996 Business History Review article. “Advertisements of funeral establishments were numerous and conspicuous in all Negro papers.”

9. Revealing migration clues

Many of our ancestors relocated numerous times, and more often than not, they neglected to leave their descendents evidence of all the moves. Thank goodness, however, that the comings and goings of individuals and families rarely escaped the watchful eyes of newspaper correspondents.

You may find an article or society column mentioning your ancestor arrived in or left town. More generally speaking, newspapers loved to inform their readership about the African-American population. You’ll frequently come across accounts of “Negro colonies” being formed in many places, particularly in the Mountain West and the Great Plains. Also expect to find recruitment advertisements for settlers and letters to the editor discussing various aspects of life inthese communities.

Pay special attention to newspapers’ memorial tributes to deceased loved ones as well as milestone wedding anniversaries—two sources genealogists routinely pass over in their search for family history clues. If you find such an item, look for similar tributes in issues published around the same date in prior and subsequent years. In tributes that repeat over multiple years, be on the lookout for changes in the residences of any relatives listed. If a contributor from a prior year is no longer listed in an annual tribute, it can be a strong indicator that he or she had perhaps migrated to the great beyond.

10. Solving marriage problems

For the genealogist, “marriage problems” can come in all forms. Finding an exact or nearly exact wedding date, figuring out whether someone married multiple times (and the identities of those spouses), determining a marriage location, and discovering the married (or maiden) names of women is enough to give you a migraine. And it’s even more painful when you step into that chasm between the 1880 and 1900 censuses. But take a look at this relatively nondescript news item tucked away in the Jan. 12, 1889, edition of the Savannah Tribune:

Mr. James F. Wand, a popular barber in the employ of E. R. Spaulding, Lake Street, and Miss Mary L. Brown of Savannah, Ga., were married on Tues last, in Philadelphia. Mr. and Mrs. Wand, have arrived in Oswego, and have taken rooms with Mrs. Dorsey, on Spencer Avenue. —Oswego Times.

Fortunately for you, wedding and engagement announcements are abundant in newspapers. Also coming to your rescue are memorial tributes and announcements about deaths and funerals, noteworthy wedding anniversaries, reunions, and countless visits to relatives near and far.

11. Gaining African American perspective

Arguably, the most important mandate for editors and publishers of African American newspapers was to provide their community of readers with news that was relevant and significant to their lives. During the Reconstruction years (1863 to 1877) and the Jim Crow era (1876 to 1965), such news differed drastically from what was being published in mainstream newspapers. Through the black press, our ancestors were able to find encouragement and direction. They could validate their worth by reading stories about fellow African-Americans who were intelligent, industrious, successful, of good moral character and willing to exercise their newly acquired rights. There’s no better way to gauge the way your ancestors and their contemporaries thought and felt than to read the news that they read.

African American newspapers are an indispensable part of your research plan. From their pages will spring the vital clues you need to solve many a genealogical mystery, along with rich and relevant stories of the black experience that will allow you to build an accurate, substantive family history. When embarking on a research journey into African-American newspapers, prepare for an exciting and rewarding adventure. And expect the unexpected: Marvelous surprises await the zealous newspaper researcher.

Tip: Besides typing names into searchable newspaper databases, try keywords such as your ancestor’s hometown or neighborhood, occupation, military unit, church, school or hobby.

Where to Find African American Newspapers

I’m happy to report that thousands of African American newspapers from the late 19th and early 20th centuries have survived and are waiting for you to find them. Locating them can be a bit of a challenge, but several useful sources can help you:

- Chronicling America, part of the Library of Congress, has a searchable directory of historical US newspapers. The site has more than 2,000 black newspapers cataloged, and more are being added. You can search for newspapers by place; limit your search to African-American titles by looking for the Type of Newspaper portion of the search form and using the Ethnicity Press dropdown menu. Matches show you each newspaper’s publication information, libraries that hold that title and what issues they have.

- University of Georgia Libraries has a large collection of African-American newspapers on microfilm, and you can download a list of holdings by newspaper title and by state from the university’s website.

- Digitized records collections have taken genealogical research to a whole new level, African-American roots included. GenealogyBank provides access to millions of digitized historical newspaper pages by subscription. Since launching an African-American newspaper collection of 61 titles early in 2010, the site has consistently added new titles and extended holdings of existing ones. Search by name at GenealogyBank.com; click Advanced for a keyword-search option. You’ll find many of the titles are fairly recent, published in the late 20th century. Nevertheless, the collection has two papers I consider in the top 25 for genealogy research: the Freeman of Indianapolis (1888-1916), and the Savannah Tribune of Georgia (1875-1922).

You’ll find other digitized African American newspaper collections on Accessible Archives (offered through some libraries or by individual subscription) and in ProQuest’s Historical Black Newspapers, available through some libraries. Freedom’s Journal, America’s first black newspaper (New York, 1827-1829), is free at WisconsinHistory.org.

After finding titles relevant to your research, gaining access to them may be as close as the front door of your local public or university library. Even if it doesn’t have the newspaper you need, someone on the staff, usually the reference librarian, is equipped to help you obtain your selections through interlibrary loan. The newspapers are most often in microfilm format, so you should make sure the library has a working reader on site.

The History of African-American Newspapers

America’s black press has its roots in the founding of the country. As the 13 Colonies were declaring their independence in 1776, a number of other significant changes were sweeping the landscape. “In New England, newspaper coverage of blacks entered a new phase as the abolition of slavery became an important and highly charged topic that would last until the Civil War in the 1860s,” writes Patrick S. Washburn in The African American Newspaper: Voice of Freedom.

The rising anti-slavery movement didn’t directly address the difficulties and concerns of the hundreds of thousands of free blacks then living in the Colonies. To them, it was abundantly clear that they were not “free” politically, economically, socially or in many other respects. Therefore, a half-century after the Declaration of Independence was authored, African-Americans made their own declaration of sorts by launching the first black newspaper.

“We wish to plead our own cause. Too long have others spoken for us,” declared Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwurm on the first page of Freedom’s Journal. The country’s first African American-owned and -operated newspaper began in 1827, but lasted only a few years (view digitized issues on the Wisconsin Historical Society website. From the first issue, you can find marriage and death notices. The newspaper was followed by a procession of others, including William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, which ran from 1831 to 1865, and Frederick Douglass’ North Star (1847-1851). The North Star then merged with the Liberty Party Paper to form Frederick Douglass’ Paper, which openly endorsed abolitionism through politics (as opposed to appeals to Americans’ personal consciences).

Each paper contributed to the education of the African-American community in a way no other newspaper would. This was evident in Willis A. Hodges’ Ram’s Horn, started in 1847. In his 1972 thesis The Black Press and the Search for Identity, Lester Pope reveals that Hodges began the newspaper “after he attempted to gain space for Negro news in the New York Sun and was told, ‘The Sun shines for all white men, but not for colored men.'”

With the end of the Civil War came a pressing need to assimilate and educate the millions of slaves now experiencing freedom for the first time. In the aftermath of the war appeared a steady stream of black newspapers in the South, one of the earliest being the Colored Tennessean in Nashville. Although the literacy rate among freedmen would never reach 100 percent, it didn’t diminish the African American’s appetite for black newspapers. Frederick G. Detweiler’s book The Negro Press in the United States documents that it was “a common custom for a group to listen as someone reads the paper aloud … an observer in the far South saw the Freeman of Indianapolis draw a circle of auditors in a small-town barber-shop soon after the paper arrived on the train.”

The mission of the black press was clear in the minds of publishers and editors as they served the perceived needs of their audience. Often this was vividly displayed in the masthead of the paper. The State Capital, published in Springfield, Ill., proclaimed, “Give Us Justice; More, We Do Not Ask; Less, Will Not Content Us.”

Among the most comprehensive sources of information on the black press is a PBS documentary, “The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords.” Its companion website is rich with links and resources, including a timeline, and profiles of four iconic newspapers: the Chicago Defender, California Eagle (based in Los Angeles), Afro-American (based in Baltimore) and Pittsburgh Courier.

A version of this article appeared in the May 2011 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT