Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

To successfully trace your Czech or Slovak ancestors in Europe, you’ll need two key clues: the immigrant’s original name and hometown. Prepare yourself for a challenge — the changing town and county names, confusing geographical borders, exotic-sounding surnames and unfamiliar languages can frustrate even the most experienced researcher.

Turn first to your family members for clues — they often can help you determine your ancestors’ names and village, and perhaps supply supporting documents. Remember to ask where events occurred, so you get a better sense of location. Pay close attention to the place of residence column in US passenger arrival lists and the state of origin listed in departure records. Clues in the census — such as birthplaces and languages — can focus your search. So will these strategies:

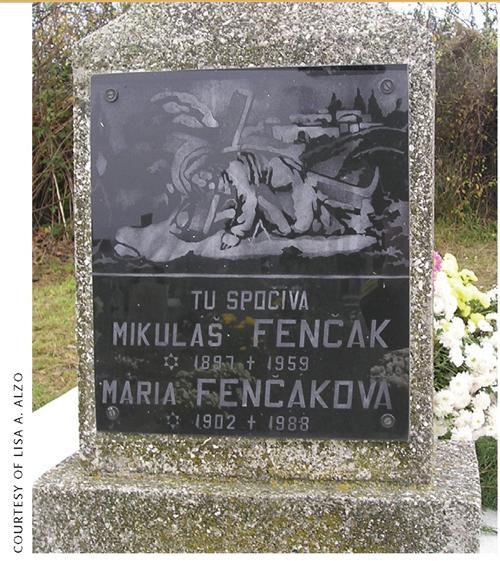

Ancestors’ names: The surrounding countries of Germany, Hungary and Poland strongly influenced Czech and Slovak names. Surname spellings often vary in grammatical context — for example, male Czech surnames may end in -úv, or -ovec. You may encounter patronymic surnames (ones derived from the father’s name, such as Janac.ek, meaning “little John,” or S. tepanek, meaning “little Stephen”), as well as surnames that reflect social status or personal features, trade or occupation. Female surnames typically have the suffix -ova at the end.

Note first-name practices, too. Orthodox and Catholic families frequently named their children for saints. You’ll need to recognize regional and cultural translations: Great-great-grandma might appear as Elizabeth on her naturalization application, Alz.beta in Slovak parish registers and Erzsébet in Hungarian census returns. Be on the lookout for spelling variations and transcription errors.

Don’t let Czech and Slovak language differences throw you — as this tombstone shows, women’s surnames include the suffix -ova.

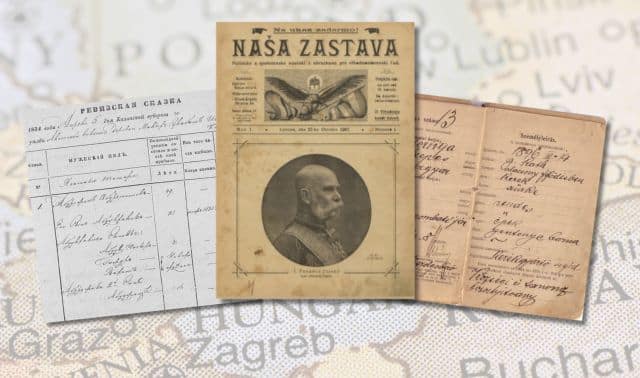

Government birth, marriage, divorce and death certificates sometimes provide specific towns of origin. If your relative appears in the Social Security Death Index (SSDI, online at FamilySearch and RootsWeb <ssdi.rootsweb.com>), you can order his Social Security application (SS-5), which contains complete birth information and the maiden name of the applicant’s mother. Church records often list the ancestral town or village, so try to track down baptismal, wedding and funeral documents. Don’t overlook other sources for vital statistics, including cemetery, burial and funeral home records; obituaries in community or fraternal organization newspapers; and state, county and town histories.

Check naturalization records, too, especially declarations of intention (also called “first papers”). But keep in mind that pre-1900 naturalizations are less likely to contain specific details, and later records may not be completely accurate. Until 1906 — when the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization (now US Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS <uscis.gov>) standardized the naturalization process — immigrants could file naturalization petitions in local, state or federal court. After 1922, the federal government began keeping separate naturalization records for married women. Children younger than 16 appear on their fathers’ naturalization records. From 1940 to 1982, the government required foreign residents older than 14 to complete alien registration forms.

You can get copies of alien registrations and post-1906 naturalizations under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). Submit a written request to USCIS using form G-639, which you can download from <uscis.gov/graphics/formsfee/forms/files/g-639.pdf>.

Once you’ve found the name of your ancestral town or village, you’ll need to determine both its pre- and post-WWI locations using maps and atlases and gazetteers — because of the postwar political changes, some towns and villages were renamed or referred to in different languages. Gazetteers are geographical dictionaries listing all the towns in a particular country; they also tell you which political jurisdictions (provinces, counties, districts) each city fits into, how many residents practiced various religions and where the inhabitants went to church.

The FHL has an extensive collection of maps and gazetteers — check the online catalog for microfilmed items you can borrow through an FHC. Note that the library catalogs its Czech and Slovak materials based on spellings in the 1929 gazetteer Místopisny´ Slovník Ceskoslovenské Republiky (film number 1183708).

ADVERTISEMENT