Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

We hope you enjoy your limited-time free access to this premium article. If you like what you see, sign up for our Family Tree Magazine Plus subscription to get access to thousands more how-to genealogy articles.

Democrats, Republicans and Democratic-Republicans

Republicans accused Adams of favoring a return to a monarchy and supporting a tyrannical central government. Federalists branded Jefferson an atheist and a Revolutionary War shirker, linking him to the French Revolution. Adams won a narrow victory, 71 to 68 electoral votes. Under the system in place until the 12th amendment passed in 1804, as the second-place finisher, Jefferson became vice president.

That awkward arrangement led to the even more contentious campaign of 1800, the only election in which a sitting president faced his own vice president. Many historians consider this the nastiest campaign ever. While the candidates sought to stay above the fray, they slyly employed surrogates and writers to slam the opposition. One Jefferson hired memorably called Adams “a hideous hermaphroditical character which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.”

Federalists again accused Jefferson of atheism and having an affair with one of his slaves, warning voters of the dire consequences of a Jefferson victory: “Are you prepared to see your dwellings in flames… female chastity violated… children writhing on the pike? Great God of compassion and justice, shield my country from destruction.”

Even the distinguished president of Yale University removed his gloves, warning that if Jefferson were elected, “we would see our wives and daughters the victims of legal prostitution.”

Hamilton’s Critique

Perhaps most damaging was the written criticism from Adams’ fellow Federalist, Alexander Hamilton, who instead supported Charles Pinckney. Hamilton’s 54-page critique of Adams became public after a copy fell into the hands of a Democratic-Republican.

The nastiness lasted from April to October, because each state could choose its own election day. By autumn, the Electoral College was tied at 65-all, leaving last-to-vote South Carolina to deliver the election to Jefferson and running mate Aaron Burr, 73 to 65.

The Democrat-Republican electors’ plan to avoid giving Burr the presidency was for one elector not to vote for him. When that plan fell through, leading to a tie between Jefferson and Burr, the decision went to the House of Representatives. It took 36 votes for one of the candidates—Jefferson—to achieve a majority.

Smear Campaigns

In 1824, Adams’ son, John Quincy Adams, was involved in another of America’s nastiest campaigns—and a rematch. Despite trailing in electoral votes, Adams defeated Andrew Jackson in the four-way race, again decided by the House.

In 1828, Adams’ backers pulled out all the stops, distributing what became known as the “Coffin Handbills.” The papers depicted six black coffins representing soldiers Jackson had executed for desertion. Another handbill accused Old Hickory of cannibalism. After massacring 500 Indians, it charged, “the blood thirsty Jackson began again to show his cannibal propensities, by ordering his Bowman to dress a dozen of these Indian bodies for his breakfast, which he devoured without leaving even a fragment.”

The Adams campaign also targeted Jackson’s marriage to Rachel Donelson, whose unhappy first marriage ended in divorce—but not, opponents charged, before she took up with and married Jackson. She was accused of bigamy, Jackson of adultery: “Ought a convicted adulteress and her paramour husband to be placed in the highest offices of this free and Christian land?”

In response, Jackson’s campaign claimed Adams had acted as a pimp while in Russia. Adams was said to have advanced his career and moved up to ambassador by providing the czar with the sexual favors of an American woman. Jackson won. He never forgave Adams, whom he blamed for Rachel’s death from a heart condition before his inauguration.

The acrimony of the Civil War and its aftermath replaced campaign mudslinging for much of the mid-19th century, culminating in the contested election of 1876. Although Democrat Samuel Tilden beat Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in the popular vote, electoral votes from four states were disputed. In a deal that made Hayes president, Republicans agreed to end Reconstruction and remove troops from the former Confederacy.

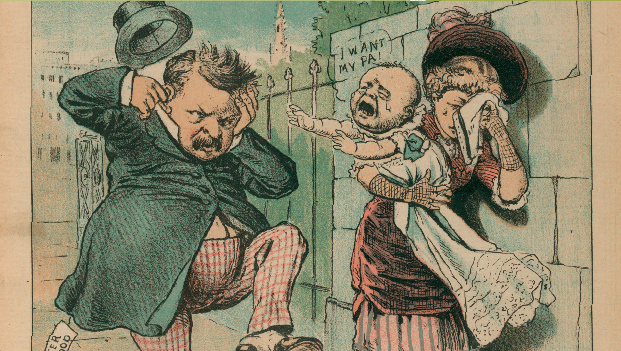

Grover Cleveland’s Child

By 1884, campaigns returned to character assassination. Backers of Republican James Blaine—derided by Democrats as “the continental liar from the state of Maine”—dug up dirt on Grover Cleveland: As a bachelor, Cleveland had fathered a child with a widow, Maria Halpin. Blaine’s backers drafted a cartoon of a child reaching from his mother’s arms to Cleveland, calling, “Ma! Ma! Where’s my pa?!”

The candidates themselves mostly still avoided active politicking, after Martin Van Buren’s 1840 re-election tour was denounced as undignified and insulting. Presidential challengers began to stump, though, with the 1896 campaign, during which the ultimately unsuccessful William Jennings Bryan logged 18,000 miles. But campaigning was thought un-presidential for incumbents—a nicety Theodore Roosevelt, during his 1904 re-election bid, likened to being a Rough Rider and “lying still under shell fire.”

The Television Age

Soon, however, radio, newsreels and television brought campaigns into Americans’ homes. Dwight Eisenhower was first to air campaign commercials, 20-second spots showing the war hero answering questions from ordinary folks.

The 1964 Daisy Ad

Campaigns in 1996 used the internet, but for little more than online brochures. By 2008, the web was a tool for organizing, fundraising and the art of winning over voters via Twitter.

Do you have a president in your past? Trace your roots to the White House with this step-by-step guide.

A version of this article appears in the October/November 2016 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Pin this for later:

ADVERTISEMENT