Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

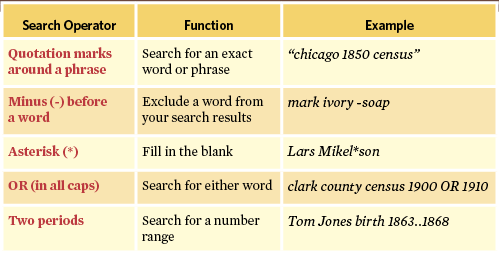

You likely already know you can power up your genealogy web searches by clicking the Advanced Search or More Search Options button on sites such as Ancestry.com, MyHeritage.com and Archives.com. And by now, you also probably know to enclose phrases (such as an ancestor’s first plus last name) in quotation marks when searching Google or other search engines. Be sure to try these four strategies, too, for more productive research sessions.

1. Home in on places and dates.

For example, you can exclude terms from a Google search using a minus sign (such as -Massachusetts),letting you remove results unrelated to your search. You also can search a specific genealogy site through Google, including most subscription services, allowing you to drastically reduce superfluous search results. For example, entering site:rootsweb.com or site:findmypast.com as part of your search focuses on just those domains. And if you’re looking to broaden, rather than restrict, your search, you can use a tilde (~) to search for terms related to a particular keyword (for example, ~military also searches for army).

Individual genealogy websites also have their own tricks for more fruitful searching. You’ve probably played around with the date-range options on sites like Ancestry.com and Archives.com (where a dropdown menu lets you choose plus or minus one, two, five or 10 years),

findmypast.com (0-40 years) or MyHeritage.com (plus or minus one, two, five, 10 or 20 years under “Match Flexibility”).

But did you know you can specify a range of years in a Google search? Just separate the dates with two dots (no spaces), such as: 1823..1852.

Another search feature worth trying is the “Any” event option (in

FamilySearch.org, Ancestry.com and MyHeritage.com) or “Other Event” (in findmypast.com). This lets you search for records that aren’t necessarily birth, marriage, death or other pre-specified options. It’s one way to narrow the time frame of possible records without inadvertently omitting something important.

2. Use wildcards creatively.

When searching for names, you can sometimes use wildcard characters to unearth records that otherwise would stubbornly stay “hidden.” On Ancestry.com, findmypast.com and FamilySearch.org, you can type a question mark (?) to take the place of any single character, or an asterisk (*) to stand in for any number of characters. When searching the 1850 US census on Ancestry.com for my ancestor James Lowe, born in Georgia in 1812, a conventional search came up frustratingly empty. But when I tried again using a wildcard, as in Low?, he popped right up. The problem with my original search? His last name had been mis-transcribed as Lowd, a spelling Ancestry.com recognized with the use of the wildcard.

Note, by the way, that if I’d tried an asterisk instead (Low*), I would still have found my missing ancestor. But I would’ve had to wade through extraneous surnames like Lowell and Lowenstein. Asterisk searches are worth keeping in mind, though, as my family originally spelled it Low, with no e. Thus Low? finds only surnames with one (no more, no less) character after the w, while Low* would also find those with zero characters after the w.

Another way around this roadblock is

Stephen P. Morse’s One-Step Webpages. This clever site “drills down” into immigration, census and other databases to let you search with a single click. Because its options include “Starts with” for names, I could search for Low and get Lowd, Lowe and Low, as well as Lowell.

Unfortunately, neither Archives.com nor MyHeritage.com allows wildcard characters. Nor does Google let you use wildcards to stand for letters, but it does have a nifty trick in which an asterisk takes the place of a whole word. This is particularly handy when combined with quotation marks to enclose a phrase. For example, “John * Depenbrock” finds John W. Depenbrock and John Henry Depenbrock. You even can combine multiple asterisks, separated by a space: “John * *Depenbrock.”

3. Leave off the name.

In certain circumstances, you can succeed by searching without a name at all. This works in Ancestry.com, findmypast.com, MyHeritage.com and FamilySearch.org. To keep from being overwhelmed by results, you should search only a single data source—the 1850 US census, for example—and enter at least a date and place. Searching without a name but entering an 1827 birth date, Alabama as a birthplace and Macon County, Ala., as a residence, I quickly found my collateral relative Alpheus Chapman. Searching by name might have been problematic, as his first name was transcribed as Alphas.

Keywords also can help you find ancestors when simple first name/last name searches fail. Allowed by most subscription sites, these can include associations (Freemason), churches (Lutheran), ship names (Lusitania) and titles (Reverend, Doctor). Searching for my great-great-uncle Rev. Walter Phelan Dickinson, for example, can be tricky because he often simply used initials (WP). But I found him in several directories I might otherwise have missed by searching for Dickinson in Alabama, keyword Reverend.

Of course, you also know to try nicknames and alternate spellings of names in addition to initials. But it’s easy to overlook some spellings. Check the handy FamilySearch Standard Finder for ideas. (There’s also a Standard Finder that can help with places.)

4. Search sideways.

When you’re really stumped, try working sideways. Search for all you can discover about your ancestor’s siblings, aunts and uncles, cousins and even neighbors. This can be especially critical when searching for those elusive maiden names. For example, in researching Elizabeth Bradbury, I found her in her father John’s 1860 census listing in Pennsylvania, along with a brother, Samuel. Seeking to learn everything I could about Samuel Bradbury, I looked for him in Illinois, where Elizabeth had later moved. Sure enough, there he was in Ancestry.com’s Illinois deaths and stillbirths index. That 1926 entry for his death also listed his father, John Bradbury, and his mother—under her maiden name—Mary Jones.

Don’t forget, by the way, to search for women under both their maiden and married names. If I’d thought to search for Elizabeth using her married name, I could have saved myself some trouble and found her in the same database.

Keep an eye out, too, for people with different last names in an ancestor’s household—they might be clues. For instance, that 1860 John Bradbury entry included 17-year-old Samuel Jones. Now that I know Mary Bradbury’s maiden name was Jones, I realize Samuel is likely her brother or nephew.

Investigating common surnames like Jones can be a challenge, of course, so you may have to try another sideways strategy: Identify a relative with an unusual first name and search for that person rather than your ancestor, who may very well be on the same page or in an adjacent record. If Mary Jones had a brother named Ignatius Alfonso Jones, for instance, it would be much easier to track down her brother first.

You can also try playing one site off against another. Stumped at FamilySearch.org? Try at findmypast.com and then use the info you gather there back at FamilySearch.org or Google to find clues that can fine-tune your search.

Sometimes going sideways is the best way to keep your ancestor search moving in the right direction—backwards in time.

From the December 2014 Family Tree Magazine