Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

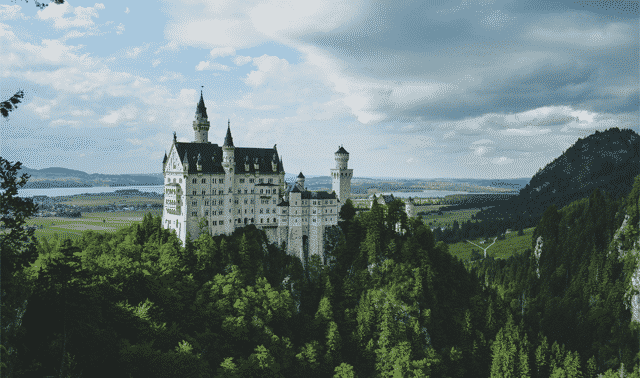

What does it mean to have German roots? Well, it might account for your fondness for lederhosen and plumed hats, as well as your sauerbraten cravings. And it likely explains why, at last year’s family reunion, you felt compelled to grab your beer stein, climb atop a picnic table and lead the clan in a raucous singalong (at least that’s what you can tell your spouse).

Having German roots also means you’re in good company: More than 40 million Americans claim to be of Deutsch descent, making it the country’s most common ancestral group. You share your heritage with some of America’s most notable historical figures, including presidents (such as Herbert Hoover), scientists (Albert Einstein), business magnates (John Jacob Astor) and writers (Dr. Seuss).

Genealogists will find strength in those numbers. You have a wealth of resources and a wide support network to help you discover your past. And you’re just as fortunate when it comes to documenting your family history: Germans have been meticulous record-keepers throughout their long history—beginning with the mostly tiny, independent German states that sprung up during the Middle Ages and continuing beyond their 1871 unification. To trace your ancestors in the old country, you’ll need an understanding of Germany’s history, its records and your family’s path to America.

1. Understand a Bit of German History

Germans were around long before there was a Germany—some 2,000 years before, as a matter of fact. During the fourth and fifth centuries, Goths, Vandals, Franks, Alemanni and other Germanic tribes established decentralized feudal mini-states, from which modern Germany evolved.

German national consciousness gained its first hero in Charlemagne, the warrior king who became Holy Roman Emperor in 800. Charlemagne united much of what’s now France, Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and Italy. France eventually became its own kingdom, but the small, feudal German states remained independent, linked only by the concept of the emperor. Civil strife erupted in Germany each time the throne changed hands.

The ascension of the House of Hapsburg during the 1400s ended this shuffling of dynasties. But a German monk named Martin Luther created another upheaval in 1517, when he nailed 95 theses disputing Roman Catholic Church practices to Wittenberg’s cathedral door. That led to the Reformation and the founding of the Lutheran Church, as well as other Protestant denominations.

Religious disunity and political chaos ripened the country for the Thirty Years War from 1618 to 1648, resulting in the deaths of an estimated one-third of the German population. Then, in the 1680s, King Louis XIV of France invaded the Rhineland, spurring German immigration to America over the next two decades. The Hapsburg family also encouraged its subjects to settle the empire’s eastern territories—to create a buffer from the Ottoman Empire, which was expanding through Eastern Europe.

In the early 1800s, France’s Napoleon I conquered much of Europe and reorganized the German states. After his defeat in 1815, the Congress of Vienna gave the Kingdom of Prussia, which began as a northeastern German state with a capital in Berlin, leadership of German-speaking Europe. Prussia grew stronger and reached its zenith in 1871, when its king was declared emperor of a unified Germany—which didn’t include Hapsburg-ruled Austria.

The German empire became a world power in the early 20th century, but still ended up on the losing side of World War I and ceded its eastern lands to Poland. Germany lost more land after its defeat in World War II, and was divided into East and West for more than 40 years—becoming a unified nation again only 14 years ago.

Today, Germany remains a large European nation: It’s slightly smaller than Montana, but with 80 million people, it has about 10 times the population of the Treasure State. And that doesn’t include the regions that once had or still have large concentrations of German speakers: Austria and Luxembourg as well as parts of Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Ukraine.

2. Know Dates of German Immigration

Your own family’s path of migration will figure prominently in your roots research. Germany’s states experienced two major emigration waves. In the 1700s, as many as 85 percent of migrants went east to Hungary and the Balkans—but some 80,000 people still found their way west to America. The 1800s saw larger-scale immigration to America, with up to 5 million crossing the Atlantic. Although this second wave brought many more Germans to the United States, nearly equal numbers of Americans descended from each group because of the earlier crowd’s head start.

These two groups’ places of origin, motivations, economic classes and religions differed significantly. If your German ancestors were 18th-century emigrants, they probably came from the states of the Palatinate, Baden, Württemberg, Saarland or Alsace (a mostly German-speaking border area now in France). These folks were mostly Lutheran and Reformed Protestant farmers who were lured to America by land. Contrary to popular belief, only about 10 percent—including the Amish and Mennonites, today’s stereotypical “Pennsylvania Germans”—left seeking religious tolerance. The religious aspect of those groups’ emigration has been romanticized into the norm.

The 1800s arrivals—almost equally Protestant and Catholic—tended to come from Germany’s northern and eastern regions, including Saxony, Pomerania and Prussia, as well as Bavaria. This wave of immigrants included more craftsmen and entrepreneurs than the first; many of these artisans extended markets that earlier immigrants had established in the German-speaking enclaves of Pennsylvania, the Midwest and Texas. A handy source for tracing 19th-century immigrants is Ira A. Glazier and P. William Filby’s Germans to America series, which contains extracts of passenger-arrival lists (covering ships on which at least half of the voyagers were German). It’s available in print from genealogical libraries and searchable on major genealogy websites such as Ancestry.com.

The paths Germans took to depart their homeland varied by time period, too. In the 1700s, emigrants usually boarded Rhine riverboats to Rotterdam in the Netherlands. From there, most ships paused at the coast of England before sailing on to America; Philadelphia was their most common entry point. During the 1800s, emigrants usually departed from Hamburg and Bremen, arriving at ports such as New York, Baltimore and New Orleans.

Unfortunately, Bremen’s 19th-century records haven’t survived, and relatively few embarkation records from the popular 18th-century port, Rotterdam, are still around. But Hamburg’s records from 1850 to 1934 are mostly intact, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ (LDS) Family History Library (FHL) has microfilmed them. You also can access those emigration records in subscription site Ancestry.com‘s database of passengers who departed Bremen between 1890 and 1905.

Tips on Tracing Early German Immigrants

Genealogists tracing Colonial immigrants often bemoan the lack of official passenger lists to help pinpoint their ancestors’ arrivals in America. But not the descendants of German immigrants to Pennsylvania—because that colony’s English officials passed laws requiring ship captains to compile lists of their foreign passengers. Immigrants from the British Isles already were royal English subjects—rather than foreigners—so these invaluable passenger lists are unique to Germans.

The lists have been published in a three-volume work called Pennsylvania German Pioneers (Picton Press). Find it at large genealogy libraries or search it on Ancestry.com. Aside from the obvious benefit of pinpointing an arrival date, these records present a great opportunity for “cluster genealogy”: If you don’t know your family’s village, look for their shipmates whose hometowns are recorded—they may be your ancestors’ neighbors. A good number of the lists show signatures of male immigrants ages 16 and above, which you can compare to wills and deeds to straighten out identities in cases of common names. Some records even give ages and list women and children.

3. Find German Origins in the Home Country

Once you’ve identified your German immigrant ancestors, you’ll need to learn the name of their home village (Heimat)—that’s the key to tracing your family further. Look for this information in American sources such as church records (especially those for marriage and burial), family Bibles, old letters, newspapers, naturalization records, tombstones and 19th-century passenger lists.

But don’t be fooled: It’s not quite as simple as it sounds. Be prepared for Anglicizations (what we call the Palatinate is actually die Pfalz) and misspellings (Wortemburg instead of Württemberg). After all, American record-takers weren’t intimately familiar with German geography and language. You’ll also need to understand Germany’s administrative divisions, so you don’t spend eons searching for a town called Kreis Wittmund when that’s actually the name of a district.

A gazetteer, or geographical dictionary, can help you pinpoint the town name (including historical or foreign names), its location and nearby parishes—which you’ll need to find church records. Your best bet is the 1912 Meyers Ortsund Verkebrs-Lexikon des Deutschen Reichs, also called Meyers Gazetteer (Genealogical Publishing Co.). It’s searchable free online and available on microfilm from the FHL and at large genealogical libraries.

With the town name, you can figure out which archives likely hold your family’s records. Perhaps reflecting its long history of disunity, Germany’s approach to archives is likewise decentralized. The modern political subdivisions of Germany generally date from after World War II. Germany’s equivalent of a US state is the Land; its Kreis is similar to a US county. A city is known as a Stadt. Records helpful to genealogists—archived civil registration records, tax lists and guild registers—are generally found at county archives (Kreisarchive) or city archives (Stadtarchive). A Kreisarchiv typically holds records from villages too small to have their own archives. A church records system comprises separate archives for Protestant and Roman Catholic records.

Shirley J. Riemer’s German Research Companion (Lorelei Press) gives contact information for civil and church archives at all levels. Before requesting information from archives, read the FamilySearch Wiki’s German letter-writing guide for tips on how to address the envelope, how to write the letter and what to expect in the way of a response.

But don’t pull out your pen and paper or book a flight to Germany just yet. German records are widely available in the United States, so you can learn a lot about your family without bombarding the post office or boarding a plane. Let’s look at some of those sources and places to find them.

4. Research Ancestors Using These Helpful Records

If there’s one thing you can say about Germans, it’s that they’re methodical record-keepers. (If you’ve ever seen a Pennsylvania German headstone, you know what I mean.) Many researchers assume that all the wars fought on German soil destroyed the bulk of the country’s records. In truth, relatively little record loss occurred during the World Wars because industrious Germans had archived and/or duplicated many historical documents long before the 20th century. Most destroyed records date from the Thirty Years War.

Here’s a rundown of helpful records for your research:

Civil registration

The government began keeping Zivilstandsregister (also called Personenstandsregister) throughout Germany in 1876, but some states started civil registration in the late 1700s and early 1800s, while they were under French rule. The FHL has microfilmed most of these early registrations. To find them, search FamilySearch’s catalog for your family’s town, and look under the Civil Registration heading. Unfortunately, privacy laws protect post-1875 German registrations. Recent records are held locally, and only close family members can access them. Older registrations are sent to a Kreisarchiv or Stadtarchiv—but there’s no hard-and-fast rule governing when this happens.

Church records

Genealogists generally find these records—called Kirchenbücher in Germany—to be the most useful to their research. A few baptism, marriage and burial registers stretch back to the 1500s, but most start in the 1600s. The FHL has microfilmed many church-record books; in general, coverage is better for western Germany than the former East Germany. One potentially confusing quirk of the FHL system: It groups villages under their 1871 jurisdiction—which could be a kingdom, duchy or county—in the pre-WWI German Empire. For instance, if you look for the city of Kaiserslautern (in Rheinland-Pfalz), it comes up under Germany, Bayern, Kaiserslautern. In 1871, the city was under Bavarian (Bayern) rule.

Germany’s two major Protestant groups, Lutheran and Reformed, united as the Evangelical Church during the 1800s. So in some cases, a town will have Lutheran, Reformed and, later, Evangelical church records. Protestant books are in German, written in a Gothic script that can be difficult to decipher. Many Roman Catholic records also have been microfilmed. They’re usually easier to read because they’re written in Latin, using the Roman alphabet familiar to English speakers.

FamilySearch online databases contain millions of names abstracted from German church books—mainly baptisms and marriages—and other records. This makes FamilySearch a great starting point when you’ve identified an immigrant ancestor but have no clue where in Germany he or she came from. Since the member-submitted names aren’t verified, though, be sure to check in original records. If there’s no record image associated with a search result, study the citation to determine the information source, and try to get that record. There’s usually more information in the original record; for example, it would list baptism sponsors or the fathers of a newlywed couple—giving you a head start on the previous generation.

Manumission records

When a German received official permission from his lord to leave the estate, he received a letter of manumission. These records can be especially useful for the 1700s. The late Werner Hacker spent decades compiling lists of manumissions from southwest Germany, which he published in 10 volumes. Though they’re now out of print, you still can find them at the FHL and major academic libraries. An English-language summary, Eighteenth Century Register of Emigrants from Southwest Germany to America and Other Countries (Closson Press) includes names and villages from many of Hacker’s volumes. Of course, thousands of emigrants left illegally and don’t appear in manumission lists. During the 1700s, these “illegals” were avoiding exit taxes (some German states even taxed future inheritances); in the 1800s, they were skipping out on an evermore-inclusive military draft. In general, manumission records end during the 1800s—the exact dates vary from state to state depending on when each lord freed his serfs.

Tax lists and guild registers

These documents often stretch back into the Middle Ages, and can help identify a family or, in the case of guilds, show a father-son relationship. The FHL has microfilmed just a fraction of these records, but a fair number have been published. You can find those in Der Schluessel (The Key), which acts as a German-language equivalent of the Periodical Source Index (PERSI), the leading guide to English-and French-language genealogy articles. Der Schluessel summarizes articles—including surname references—in nearly 100 periodicals dealing with genealogy and heraldry of German-speaking people. It’s indexed by subject, surname and location, so you can study a family or a geographic area. The Library of Congress in Washington, DC, has nine printed Der Schluessel volumes covering 1950 to 1986. Other large genealogical libraries have smaller Der Schluessel collections. Once you find an article, check the FamilySearch catalog—many of these periodicals were once recorded on microfilm.

5. Refer to These Tips for Translating German Records

You’re probably thinking, “But most of these records are in German, right?” That’s true, but don’t assume that lack of German fluency is a problem. Most German record groups follow some sort of template (birth dates in one column, parents’ names in the next and so on) — figure it out, learn a few key terms, and you’re on your way to deciphering the record. FamilySearch’s German Genealogical Word List will help.

Since Protestant, civil and even some Catholic records were written in a Gothic script that initially looks remarkably similar to chicken scratches, you’ll want to learn that alphabet. Consult Edna M. Bentz’s If I Can, You Can: Decipher Germanic Records (self-published). Reading Gothic script often involves translating one letter at a time using a key that shows Gothic and standard alphabets side by side (such as the chart in our German Genealogy Cheat Sheet). It’s slow going, but you’ll get faster with practice.

German immigrants tended to settle in clusters, so many of their US records—church registers, newspapers and deeds—are in their native language. And when German-speaking farmers encountered English-speaking clerks or census takers, outlandish name spellings often resulted. For instance, a Pennsylvania Revolutionary War soldier named Dielman Daub shows up in the 1790 US census as Teelman Toup, while the 1753 immigrant Caspar Kreiser is Jasper Grasore on a tax list.

Part of the pronunciation problem came from two little dots. Germans sometimes put two dots, called an umlaut, above a vowel instead of adding an e after it. Some modern Germans favor eliminating the umlaut, but historical records have them by the bucketful. Umlauts altered the way a name sounded enough to create new spellings. The German name Krück, for example, pronounced roughly as “Krhook,” eventually transformed itself into Krick, Crick and Creek. Another strange-looking symbol you’ll see in older records is the ß, called an s-set, sometimes written as ss today.

You also may find yourself struggling with families that seemed to name all the boys Johann and the girls Maria (the equivalents of John and Mary). For centuries in Germany, the first name was a “prefix name” given at baptism. What we’d consider a middle name was the Rufnahmen (“call name”) that the individual actually used. This tradition, too, was carried to America. Especially in American records, you may find that Johann Christian Miller, whom everyone knew as Christian Miller and who appears in records as such, ends up with a will or other document filed under Miller, John C.

All this spells plenty of possibilities for discovering your German roots. Eventually, though, you may exhaust all avenues of research on this side of the Atlantic, or just want to see your ancestors’ homeland firsthand. If you’re planning an overseas research trip, consult Roger P. Minert and Shirley J. Riemer’s Researching in Germany (Lorelei Press) for further guidance. And be sure to make time for drinking up the atmosphere of your ancestor’s hometown, perhaps visiting the house where she was born or meeting modern residents who share her surname. Combine that with a German beer at an outdoor cafe, and you’ll have the recipe for the trip of a lifetime.

6. Utilize German Genealogy Websites, Books and Groups

Websites

- ThoughtCo. Genealogy Basics

- Cyndi’s List — Germany

- FamilySearch Wiki: German Genealogy

- Genealogy in Pfalz

- GenWiki German Genealogy

- German Culture

- German Genealogy Home Page

- Google Translate

- Meyers Gazetteer Online

- Portal Archive in Baden-Württemburg

Books

- Ancestors in German Archives by Saskia Schier Bunting, Mirjam J, Kirkham, Nathan S. Rives and Raymond S. Wright (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Eighteenth Century Register of Emigrants from Southwest Germany to America and Other Countries by Werner Hacker (Closson Press)

- A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Germanic Ancestors by S. Chris Anderson and Ernest Thode (Betterway Books)

- The German Research Companion by Shirley J. Riemer (Lorelei Press)

- If I Can, You Can: Decipher Germanic Records by Edna M. Bentz (self-published)

- In Search of Your German Roots by Angus Baxter (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Master Index to the Emigrants Documented in the Published Works of Annette Kunselman Burgert by Annette K. Burgert (AKB Publications)

- The Palatine Families of New York, 1710 by Henry Z. Jones Jr. (self-published)

- Pennsylvania German Pioneers compiled by Ralph B. Strassburger and William J. Hinke (Picton Press)

Genealogy Groups and Archives

- Archives in Hessen

- German Genealogy Group

- Germanic Genealogical Society

- Karlsruhe General State Archives (Generallandesarchiv Karlsruhe): Write to this archive for historical records from Baden and parts of Palatinate.

- Koblenz City Archives (Staatsarchiv Koblenz): Write for historical records from the Rhineland area.

- Mid-Atlantic Germanic Society

- Palatine Institute for History and Customs (Institut för Pfäalzische Geschichte und Volkskunde, formerly known as Heimastelle Pfalz)

- Palatines to America

- Pennsylvania German Society

- Sacramento German Genealogical Society

- Schleswig-Holstein Archives

- Society for German Genealogy in Eastern Europe

- Speyer City Archives (Staatsarchiv Speyer): Write for historical records from Palatinate.

A version of this article appeared in the October 2004 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT