Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

No Sweat

Let’s be honest: Our ancestors smelled bad. Even though ancient Greece and Rome were famous for their bathhouses, only the upper crust partook of these pleasures, leaving the average citizen, well, crusty. The poet Ovid once complained that many of his fellow Roman men smelled as though they were carrying goats under their arms. And things went from bad to worse, olfactorily speaking, as the classical world gave way to the Dark Ages, which might more accurately be dubbed the Odiferous Ages.

Even for our more-recent ancestors, bathing was an oddity, engaged in — if at all — more for quack therapeutic purposes than for cleanliness. Elizabeth Drinker, the wife of a prominent Philadelphia Quaker, had a showering apparatus installed in her backyard in 1799, and said of the experience, “I bore it better than expected, not having been wet all over at once for 28 years past.” Well into the 19th century, some viewed bathing not as therapy but as a health hazard: In 1835 Philadelphia, the Common Council missed by only two votes passing a ban on wintertime bathing; in 1845, Boston banned bathing except when prescribed by a doctor

Although break-throughs in plumbing technology began to change both attitudes and the ease of bathing, in frontier America “bath night” remained a weekly ritual — at best — involving heating buckets of water on the woodstove. In Farmer Boy, Laura Ingalls Wilder recalled of her future husband, “Almanzo … didn’t like Saturday night. On Saturday night there was no cozy evening by the heater, with apples, popcorn and cider. Saturday night was bath night.”

In short, with only occasional exposure to bathwater and an un-air-conditioned life that typically involved more sweat-inducing labor and activities than life today, our ancestors stank.

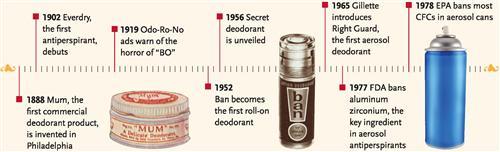

Thank goodness, then, for the inventor of deodorant in 1888 — 120 better-smelling years ago. Although the inventor’s name has been lost to history, we do know that this epochal olfactory event took place in Philadelphia. As the story goes, the inventor — perhaps a doctor? — asked his nurse to help name the new product, something homey and comforting. She came up with “Mum,” a brand name still in use today by Procter & Gamble in England.

Although Mum is generally recognized as the first product to be marketed as a deodorant, humans have been trying to cover up our odor since at least ancient Egypt. The Egyptians tried daubing their armpits with spices and citrus oils. They also came up with the innovation of trimming underarm hair to reduce the smelly surface area.

The problem the Pharaoh’s minions and Mum’s nameless creator were trying to solve is part of being human. We’re born with two types of sweat glands. Eccrine glands, numbering some 3 million all over the body, produce cooling perspiration. But it’s the apocrine glands — ironically, the same glands that make babies smell so good — that are the main culprit in body odor. Although we’re covered in apocrine glands at birth, these mostly shut down after a few months. Then at puberty, the 2,000 or so remaining apocrine glands (mostly in the armpits and groin) kick in — especially when triggered by fear or stress. The sweat itself doesn’t smell bad, but it’s a growth medium for anaerobic bacteria, which produce isovaleric acid and other stinky compounds.

Initial efforts to battle that sweaty smell concentrated on covering it up while killing the odor-causing bacteria. The original Mum was a waxy cream that came in a jar; you applied it with your fingers.

Everdry, introduced in 1902, was the first product to tackle the source of the problem and try to keep underarms dry. It used a chemical, aluminum chloride, that inhibits the activity of sweat glands. (This physiological effect is why the Food and Drug Administration regulates antiperspirants as pharmaceuticals today.)

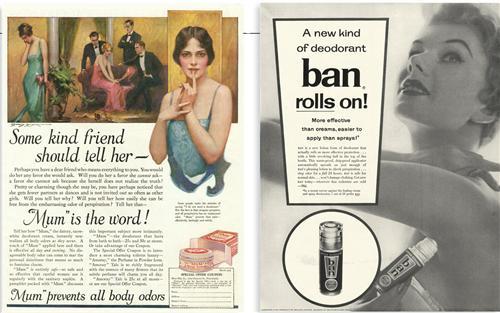

Most Americans still didn’t worry about how they smelled, however. That social transformation required advertising — an industry whose history is intertwined with that of deodorant. In 1919, a deodorant for women with the awkward but memorable name of Odo-Ro-No was the first company to use the abbreviation “BO” (but not the actual phrase “body odor”) in an ad. Notes historian Michael O’Malley at George Mason University, “Previously, deodorant ads had confined their pitch to suggestions about bow they would foster daintiness and sweetness. But Odo-Ro-No took a more direct approach, telling potential customers to take the ‘Armhole Odor Test’ and warning them that social success hinged on eliminating BO.” If you didn’t use Odo-Ro-No, the ads cautioned, you’d be “always a bridesmaid, never a bride.”

The way was paved for future products to be marketed with what historian Roland Marchand describes as “quick-tempo socio-dramas in which readers were invited to identify with temporary victims in tragedies of social shame.” Listerine mouthwash soon followed with its campaign about combating “halitosis,” and sales jumped from $100,000 a year in 1921 to $4 million-plus by 1927.

The next great breakthrough in the battle against odor would have to wait until the late 1940s, when Helen Barnett Diserens, a member of the Mum production team, was inspired by a newfangled ball-point pen. Gould the same technology used to roll out ink be applied to hitherto messy deodorant? It could, and the result of Diserens’ brainstorm was Ban Roll-On, introduced to a sweaty nation in 1952.

Aerosol came to antiperspirants in 1965 when Gillette brought out Right Guard. The notion of spraying on BO protection proved wildly popular, and by 1967 half of all US antiperspirant sales were aerosol products. Bans on the chief ingredient in aerosol antiperspirants and their chlorofluorocarbon propellant, however, deflated sales almost as quickly as they’d boomed.

For Further Reeking

Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920-1940 by Roland Marchand (University of California Press)

Chasing Dirt: The American Pursuit of Cleanliness by Suellen Hoy (Oxford University Press)

Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience by Elizabeth Shove (Berg)

The History of Plumbing in America <www.plumbingsupply.com/pmamerica.html>

The History of the Shower <www.nzgirl.co.nz/articles/2006>

Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes: A Cultural History of American Advertising by Juliann Sivulka (Wadsworth)

ADVERTISEMENT