Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Steaming Ahead

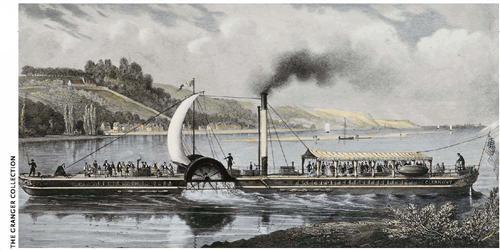

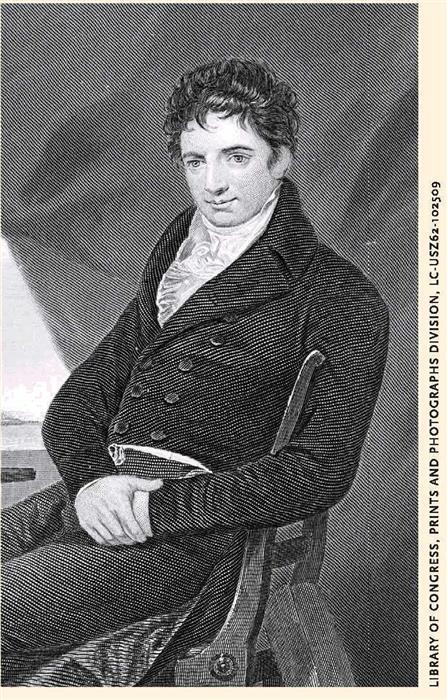

If your immigrant ancestors arrived in the second half of the 19th century, chances are their trans-Atlantic voyages were powered by steam – a technology first practically applied to ships by Robert Fulton 200 years ago.

Steam power, which Scotsman James Watt first effectively harnessed to an engine in 1765, would drive the Industrial Revolution and make humanity mobile as never before – pulled by belching locomotives and spanning the seas in ships the size of small cities. “Unlike muscle power, it never tired or slept or refused to obey,” enthused The Quarterly Review of London in 1830. “Unlike waterpower, its immediate predecessor, it ran in all seasons and weathers, always the same. Unlike wind, it responded tractably to human will and imagination: turning on and off, modulating smoothly from the finest delicacy to the greatest force, ever under responsive control. It is impossible to contemplate, without feeling exultation, this wonder of the modern art.”

Previous inventors had attempted to use the “wonder” of steam to propel a ship, and Fulton’s famous claim is riddled by controversy. As early as 1783 in France, the Marquis de Jouffray d’Abbans steamed a small boat, the Pyroscaphe, across the Seine. When Scottish engineer William Symington successfully employed steam to power another small riverboat, the Charlotte Dundas, Fulton was on board the 1801 maiden voyage.

Fulton’s father was an immigrant from Kilkenny, Ireland, in the early 18th century, sailing to America as some 4 million of his countrymen would do between 1851 and 1905 – their voyages vastly accelerated by his son’s invention. The elder Fulton settled in Little Britain (now named “Fulton”), Lancaster County, Pa., where Robert was born Nov. 14, 1765. Young Fulton was building paddlewheels by age 13. In his early 20s, he went to London, where he studied painting with renowned artist Benjamin West. By 1800, however, Fulton had returned to mechanics and engineering, developing a submarine, the Nautilus, which he tried to sell first to the French and then to the British. In a demonstration in Rouen, France, the Nautilus folded its mast and sails flat to the deck and dove to a depth of 25 feet.

Although Fulton threw himself into building steamboats (his generally sailed the Raritan, Potomac and Mississippi rivers) and the first steam-powered warship, he didn’t live to see much of the steamship age he’d launched. He caught a cold crossing the Hudson after testifying in one of the many court battles sparked by his patent, and died Feb. 24, 1815.

The steamship era sailed on. In 1819, the hybrid vessel Savannah made the first Atlantic crossing powered in part by steam; only 80 hours of the 633-hour voyage were by steam rather than by sail. In 1838, the British and American Steam Navigation Co.’s Sirius left Ireland with 40 paying passengers for a historic voyage to New York. It took 18 days and the Sirius ran out of coal – the crew had to burn the cabin furniture and even a mast – but it was the first passenger ship to cross the Atlantic entirely on steam power. The rival Great Western Steamship Co.’s Great Western left Bristol, England, four days after the Sirius sailed and arrived in New York Harbor only four hours behind it, making the crossing in 14 1/2 days. Joined by the Peninsular Steam Navigation Co. and later by the Cunard Line, the companies inaugurated the modern steamship era. They and later rivals would compete for decades over the fastest trans-Atlantic passage in what became known as the Blue Riband contest. By the turn of the century, the German vessel Deutschland had slashed the record to nearly five days.

Ships Ahoy!

• Great Lakes Historical Society/ Inland Seas Maritime Museum

480 Main St., Vermillion, OH 44089, (800) 893-1485, <www.inlandseas.org>

• Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing, Kingston, NY 12401, (845) 338-0071, <www.hrmm.org>

• J&C Maritime History Society

• Mystic Seaport: The Museum of America and the Sea

75 Greenmanville Ave., Mystic, CT 06355, (888) 973-2767, <www.mysticseaport.org>

• Palmer List of Merchant Vessels

<www.geocities.com/mppraetorius/top-com.htm>

• Queen Mary

1126 Queen’s Highway, Long Beach, CA 90802, (562)435-3511, <www.queenmary.com>

• TheShipsList <www.theshipslist.com>

• South Street Seaport Museum

12 Fulton St., New York, NY 10038, (212) 748-8600, <www.southstseaport.org>

• Steamship William C. Mather Museum

305 Mather Way, Cleveland, OH 44112, (216) 574-6262, <wgmather.nhlink.net>

Mr. Ships

After being largely destroyed by an 1822 fire, Robert Fulton’s childhood home in Lancaster County, Pa., has been restored and is now operated by the Southern Lancaster Historical Society (Box 33, Quarryville, PA 17566, <rootsweb.com/~paslchs>). The house is on Route 222 near Quarryville; for visitor information, call (717) 548-2679 or see <www.padutchcountry.com/member_pages/Robert_Fulton_Birthplace.asp>.

Fulton is buried at Trinity Churchyard in Manhattan, in the Northern Section, Livingston family vault 1815-3B. Howard Roberts Palmer’s statue of Fulton represents the commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the Statuary Hall of the US Capitol. See <www.aoc.ov/cc/art/nsh/fulton.cfm>.

From the September 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT