Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Jump to:

- Q: I’ve been searching for my Irish fifth-great-grandfather, who was born in 1748. How can I find out more about him?

- Q: I’ve hit a brick wall with my Northern Ireland ancestors before 1800. What resources can I try?

- Q: I’m looking for an obituary for an ancestor who died in Athboy, County Meath, Ireland. How can I find old Irish newspapers online?

- Q: Family lore says my Irish ancestor participated in Emmet’s Rebellion and may have been hanged as a result. How can I research this?

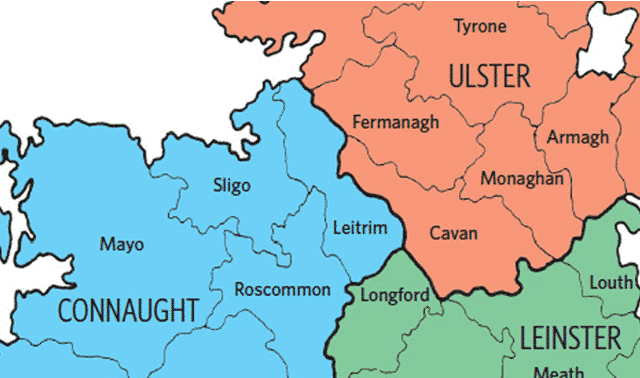

- Q: I’d like to know where in County Roscommon, Ireland, my Fallon, Caslin, Donlon and Conry ancestors came from. I’ve found them in New York in 1847, but there’s no record of them entering the United States at any of the eastern seaports. I’ve also been in touch with the Roscommon Heritage Centre and they find no trace of these folks. I suspect these ancestors entered through Canada. What’s the best course of action without a marriage or birth record? I think I need ship lists from Canadian ports of entry, but don’t know where to start.

- Q: I have several great-great aunts who came to Cincinnati from Ireland, possibly County Cork. They were Catholic nuns. How do I begin researching to find more about them?

- Q: I’m tracing my grandfather, who’s from Ireland. I have his application and final paper for citizenship, with the year. What would be my next step if I have no idea what county in Ireland he came from?

Q: I’ve been searching for my Irish fifth-great-grandfather, who was born in 1748. How can I find out more about him?

A. For Irish ancestors prior to 1864, your best resource is church records. The Family History Library has many on microfilm; find them by searching FamilySearch’s online catalog. You’ll also find some of these indexed in the FamilySearch database Ireland Births and Baptisms, 1620-1881 and Ireland Marriages, 1619-1898. The Ireland Family History Foundation has also begun to transcribe and index millions of these records. You might also try the religious census of 1766. The Irish National Archives has a list of the returns for each diocese.

Unless you get lucky and find your ancestor in an index, to trace a family in Irish church records, you’ll need to know the name of the place where they lived (the town or village) and their religion. Start your quest for this information with home sources, such as old letters, family Bibles and other papers that might have clues about your ancestral origins. You also may find it helpful to study Irish migration patterns and your relatives’ neighbors in the United States. Your ancestors may have traveled in a group with neighbors and other relatives. They might have been part of a chain migration pattern, in which family and friends followed earlier emigrants who settled in America.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

From the May/June 2015 issue of Family Tree Magazine

Q: I’ve hit a brick wall with my Northern Ireland ancestors before 1800. What resources can I try?

A: Several census substitutes can help you find pre-1800 families, according to the Ulster Historical Foundation. Indexes and originals for most are available through the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI):

Hearth money rolls: Returns for this 1660s tax on hearths are arranged by parish and list householders who paid. Surviving records cover Northern Ireland better than the rest of Ireland.

Census of Protestant householders: Not a true census, this 1740 enumeration by the collectors of the hearth tax lists names arranged by county, barony and parish.

Religious census of 1766: Church of Ireland rectors enumerated inhabitants by religion: Church of Ireland, Roman Catholic (identified as “Papists”) and Presbyterians (“Dissenters”). Some rectors simply counted heads; others listed households. The original returns have been destroyed, but transcriptions survive in the Tenison Groves Papers, available on Family History Library microfilm and on Ancestry.com.

Petition of Protestant Dissenters: This list of dissenters’ names was submitted to the government in 1775; PRONI has transcriptions. You can search an index covering the 1740, 1766 and 1775 databases at PRONI; results reference the original records.

Flaxgrowers List: In 1796, the government awarded free spinning wheels or looms to farmers who planted a minimum acreage of flax. PRONI has lists of more than 56,000 recipients. Search an index at the Ulster Historical Foundation website.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

From the January/February 2015 issue of Family Tree Magazine

Q: I’m looking for an obituary for an ancestor who died in Athboy, County Meath, Ireland. How can I find old Irish newspapers online?

A: The subscription site Irish Newspaper Archives offers more than 2 million pages in 23 papers. Its collection includes the Meath Chronicle, with all issues from 1897 to the present. Founded in 1887, the Chronicle printed detailed birth, marriage and death announcements. Because Athboy is close to the boundary between Meath and neighboring County Westmeath, you might also check the Irish Newspaper Archives’ database of the Westmeath Examiner, based in nearby Mullingar. The collection covers the Examiner from its founding in 1882 to 2008.

Check the new Irish newspapers database at findmypast.com, too. To find other Irish newspapers (including current publications) online, try bl.uk and egt.ie.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

From the December 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine

Q: Family lore says my Irish ancestor participated in Emmet’s Rebellion and may have been hanged as a result. How can I research this?

A: Named for Robert Emmet (1778-1803), the rebellion was a small uprising in Dublin July 23, 1803. Instigators hoped that it would lead to a nationwide revolt against the British. Rebels targeted Dublin Castle, which had represented British rule in Ireland since the time of King John.

But the main fighting broke out on Thomas Street, where the sight of a British dragoon being killed on the spot so shook Emmet that he tried to call off the rebellion. Many in the mob ignored him, choosing instead to drag the Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, Lord Kilwarden, from his carriage and kill him.

By the time British troops restored order that night, an estimated 50 Irish rebels and 20 military had been killed.Emmet fled but was captured Aug. 25. Convicted of treason, he delivered “the Speech from the Dock,” which became famous among Irish nationalists. He ended with this famous quote: “When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then and not till then, let my epitaph be written.”

Emmet was hanged on Thomas Street, and then beheaded for good measure. A plaque at nearby St. Catherine’s Church lists the names of 15 tradesmen and laborers hanged between September 1st and October 3rd for their part in the rebellion. Check a transcription at www.robertemmet.org/1803/tradesmen.patriots.htm to see if your ancestor is listed, and learn more about the rebellion at www.robertemmet.org.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

From the October/November 2016 issue of Family Tree Magazine

Q: I’d like to know where in County Roscommon, Ireland, my Fallon, Caslin, Donlon and Conry ancestors came from. I’ve found them in New York in 1847, but there’s no record of them entering the United States at any of the eastern seaports. I’ve also been in touch with the Roscommon Heritage Centre and they find no trace of these folks. I suspect these ancestors entered through Canada. What’s the best course of action without a marriage or birth record? I think I need ship lists from Canadian ports of entry, but don’t know where to start.

A: First, passenger lists are not going to tell you anything more than Roscommon as a place of origin in Ireland. But they may show you who immigrated together to North America and add a few more people to the picture. Unfortunately, systematic government passenger lists into Canada do not begin until 1865. However, there were scattered passenger lists for Canada before this time, and you can access most of them by searching miscellaneous pre-1865 immigration indexes at Library and Archives Canada.

I would suggest that you look at the Householder’s Index for County Roscommon. This is an index to two tax records that are used as 19th-century census substitutes in Ireland: the Tithe Applotment Books (1823-1838) and Griffith’s Primary Valuation (1847-1864). It sounds like you have a number of family names all coming from Roscommon. You may be able to find a pattern of where these surnames appear together in the tax records, and then you can consult the relevant Roman Catholic parish registers. The County Roscommon Catholic registers are available on microfilm from the Family History Library in Salt Lake City.

Also, it would be worth doing a search of the Ireland Births and Baptisms, 1620-1881 database at FamilySearch.org. This index includes more than 37,000 births and baptisms extracted from Roman Catholic registers in County Roscommon parishes. You might find your ancestors included.

Answer provided by Kyle J. Betit

Q: I have several great-great aunts who came to Cincinnati from Ireland, possibly County Cork. They were Catholic nuns. How do I begin researching to find more about them?

A. The religious orders of Roman Catholic sisters, or nuns, have kept very good records of their members. Often, this information will include the birth place of the nun and her parents’ names. Sometimes even the parents’ birth places are given! In order to find records for your great-great aunts, you need to first find out what religious order they belonged to. If you can find an obituary for one of them, it should state this information. You can also tell by the initials after their names, such as with “Sister Mary Joseph, OCD.” Religious sisters usually took on new religious names when they joined the order. The initials at the end of the name refer to their particular order or “congregation” (in this case, OCD stands for the Discalced Carmelite Nuns).

Here’s an online guide to acronyms for Catholic religious orders.

Once you have the religious order identified, then you can look up their national or provincial motherhouse/headquarters address in a modern edition of The Official Catholic Directory (P.J. Kenedy & Sons, available in libraries), which is published annually. This directory also gives the abbreviations corresponding to each religious order. Usually each order (or province of that order, if it has a large membership) has an archivist who will assist with enquiries like yours.

By the way, the same excellent biographical information can generally be found for Roman Catholic priests and religious brothers, in the archives of their religious orders, dioceses and seminaries. So in your research, don’t ignore your ancestors’ sisters and brothers who went into religious life. Their records may hold the key to important facts about your family, such as their place of origin abroad.

Answer provided by Kyle J. Betit

Q: I’m tracing my grandfather, who’s from Ireland. I have his application and final paper for citizenship, with the year. What would be my next step if I have no idea what county in Ireland he came from?

A: In most cases, Irish surnames are relatively common. Unless you have a really uncommon surname that comes from only one or two counties in Ireland, you ‘ll need to determine a specific place of origin in Ireland from US records before you go searching in Irish records.

Naturalization papers can be a good source for this information, depending on the time period and locality. Remember, you’ll want to examine both the Declaration of Intention and the Petition for Naturalization. These two documents were usually filed years apart and could have been filed in different courts. They may contain significantly different information. Websites including Ancestry.com, Fold3.com and FamilySearch.org have collections of naturalization records or indexes for various places and years.

Records generated when the immigrant ancestor died also are good possibilities for finding a place of origin in Ireland: death certificates, cemetery registers, tombstones, church burial records, newspaper obituaries, funeral home records, funeral cards. It is also helpful to know the immigrant’s parents’ names, especially the mother’s maiden name.

You should be tracing not only your grandfather, but also other relatives who came over from Ireland, to see whether their records give the county of origin. This includes siblings and other relatives who may have settled in other countries abroad. If your grandfather’s neighbors in census records show Ireland as a birthplace, it’s worth tracing those folks as well, as immigrants often traveled and settled together.

Answer provided by Kyle J. Betit

ADVERTISEMENT