Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

ROOTS GEAR

It’s a Snap

Simplify your digital-camera shopping — our genealogy-focused buying guide helps you zoom in on the model that’s right for you. ¦ By Nancy Hendrickson

Finding a digital camera couldn’t be easier — the market is flooded with hundreds of models. Some have modest features; others seem to offer everything but a professional photographer to take the pictures for you. So choosing the camera that’s best for you can seem tricky.

That’s especially true for genealogists. You have different needs than the average digital-camera buyer: In addition to snapping pictures of friends and family, you’ll use your camera to create images of old letters or journals, record family headstones, capture oddly shaped, difficult-to-scan mementos (Grandma’s teacup, for example) and perform other family history-preservation tasks.

Before you head to the camera counter, then, focus your search with this genealogy-centric buying guide. These tips will help you wade through the mine field of macros and matrix metering, and zoom in on the most important features for preserving pieces of the past.

Getting up to speed

Not every digital camera is created equal: Some have features you’ll use all the time; others have bells and whistles that might never see the light of day. Before you begin shopping in earnest, familiarize yourself with common digital-camera options and decide which ones fit your needs.

• Storage — All but the cheapest cameras come with removable storage media. The most popular types are CompactFlash, SmartMedia and Memory Sticks (Sony). The memory cards that come standard with new cameras typically hold from 8 to 16MB, but you can easily upgrade to a card with a larger capacity.

How many photos a card can hold depends on the card’s memory capacity and the resolution (dpi, or dots per inch) setting. For example, an 80MB card will hold about 130 photos at a resolution that’s great for the Web, but only 10 at a resolution that will produce a high-quality print. You won’t see a difference in quality or performance between different memory-card types — which one you choose depends mainly on your camera and personal preference.

Uniquely, Sony offers you the option of storing your photos directly onto a mini-CD-ROM that’s “burned” right in the camera. Though bulkier, this lets you store dozens of even high-resolution pictures without sweating the storage limits.

• Creative control — If you grew up with single-lens reflex (SLR) cameras, you’ll appreciate digital cameras’ many creative controls. Most models offer exposure compensation (adjusts light and dark), white balance (adjusts accurate color) and aperture and shutter priority (adjust for motion and depth of field). In addition, they usually have several metering modes to control light exposure in different portions of the picture: spot mode meters a small area of a larger scene; center mode focuses on the middle of the viewfinder; and matrix mode accounts for brightness, contrast and your distance from the subject.

These creative controls are all set to default values — meaning the camera automatically makes the smartest choices — but on some cameras, you can manually override the defaults.

• Batteries — Digital cameras come with alkaline, lithium-ion or nickel-metal-hydride batteries. Alkalines are convenient because you can buy them anywhere, but they don’t last as long as the other types. Lithium-ion and nickel-metal-hydride cells are rechargeable and come with all you need to plug in. Digital cameras eat batteries at an alarming rate, particularly if the camera has an LCD display. So if you choose a camera that uses alkalines, buy rechargeables; if you pick one with lithium-ion or nickel-metal-hydride, buy a spare and keep it charged.

• Lens — Low-end cameras come with a fixed-focus lens, so the camera automatically focuses everything from about 4 feet to infinity. Pricier cameras have an auto-focus lens, which allows you to zero in on a specific area. Some cameras also come with a 3X or better optical zoom (the lens physically moves in to get a closer shot; the number before the × measures how many times larger you can make the subject). Don’t put much stock in a camera’s digital zoom: It enlarges the subject after the shot is taken (by cropping), so you get a lower-quality image. If you want to make extreme close-ups (perhaps of a small memento), look for a camera with macro mode.

• Viewfinder/LCD — The viewfinder on a digital camera works just like the one on your film camera: Hold it up to your eye, frame the scene and shoot. Some digital models have an LCD screen that you use to compose your photo, and then instantly play it back. If you don’t like the shot, just push the erase button. Keep in mind that it’s difficult to see an LCD display in bright sunlight.

• Sensor — When light passes through the lens of a digital camera, it’s captured by a sensor that’s covered with photosensitive pixels. Cameras with more pixels on the sensor have a higher resolution and produce better images. You can get a good-quality 5×7-inch print from a 1-megapixel camera (1 megapixel equals 1 million pixels). If you want larger prints, you’ll need 2 or more megapixels.

• Flash — Most digital cameras come with a built-in flash that automatically senses when to fire. Some also come with red-eye reduction. More expensive cameras allow you to set the illumination level and use fill flash, which brightens shadowed areas.

Narrowing the field

Which digital camera you’ll choose depends a lot on what you want to spend and how you plan to use it. You’ll probably pick from one of these three categories:

• Beginner — $80 to $200. These models are the digital version of a simple point-and-shoot. They feature a fixed-focus lens and no zoom or close-up capabilities. These low-end models have built-in (not upgradable) memory, no creative control and less than 1-megapixel resolution; they may or may not have a flash.

Use: A beginner camera is fine if all you want to do is shoot people or places, and then save the images to your family tree software or share via e-mail.

• Intermediate – $200 to $500. Mid-range cameras supply all the bells and whistles most genealogists need. Features include autofocus, zoom, LCD display, removable memory cards and creative controls such as white balance and exposure compensation. They offer 1 to 2.2 megapixels.

Use: A great all-around choice for family historians. You can shoot people, places, mementos and documents. Choose either e-mail or print-quality resolution. Look for a model with macro mode if you want to convert your old slides to digital images.

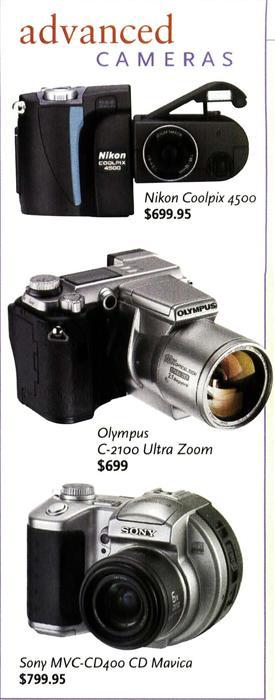

• Advanced – $500 to $900. Crammed with manual override features, these cameras have many creative controls, aperture and shutter priority and flash adjustment. High-end digital cameras have at least 3.3 megapixels and produce great picture quality. They’re the closest digital equivalent to SLR film cameras.

Use: For family history purposes, this camera won’t do much more than intermediate models, but it will give you far more control over the final output. You’ll also be able to print larger photos.

For reviews of specific models, click over to Steve’s Digicams <www.steves-digicams.com>. Look for a model in your price range with features you think you’ll use most. And go to local electronics stores to compare different models and prices — at year’s end, retailers often slash prices to attract holiday shoppers.

Once you’ve purchased your camera, there’s only one task left: developing your digital-photography skills. So have fun! Take hundreds (or even thousands) of pictures. Play with the controls. Experiment. You’ll be surprised how fast you make the transition — and how many ways you’ll use your new camera to preserve your family history.

From the December 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT