Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The Pilgrims’ “voyage to plant the first colony in the northern parts of Virginia,” as the Mayflower Compact called it, didn’t turn out quite as planned. For one thing, the party landed not in “northern Virginia” (present-day New York), but in modern Massachusetts. And for another, roughly half of its passengers wouldn’t survive their first winter.

Still, the arrival of the Mayflower in November 1620 sparked the first wave of major English settlement in New England—an important benchmark in the history of Colonial North America.

If you find Mayflower roots in your own family, you’re in good company. According to the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, an estimated 35 million people worldwide are believed to be descended from the group. Among them are some of the best and brightest Americans, from John and John Quincy Adams (through the Alden and Mullins lines) to Sally Field (through the Bradford line). This article will help you find and document your Mayflower ancestors throughout the generations.

History of the Mayflower

The historical context behind the Mayflower migration could fill several volumes. But Robert Charles Anderson’s The Mayflower Migration (New England Historic Genealogical Society) is one great resource for those curious about the Mayflower’s history. And, in 2020, NEHGS also published a special 400th anniversary edition of William Bradford’s famous Of Plymouth Plantation (a recounting of the colony’s first 30 years from Bradford’s perspective). But what follows are the most important pieces for genealogists.

Roughly two-thirds of the passengers aboard the Mayflower were members of a religious separatist community living in Leiden, Holland. (The remaining third of passengers, described as “of London” and without ostensibly religious motives, apparently joined the Leiden group in England just before the voyage.)

These separatists felt the Church of England, the state church in their home county, had too many excesses and abuses, and so wanted to separate from it. They moved to the Netherlands from several different communities to practice their religion as they saw fit, free from persecution.

But the separatists in Leiden, concerned they might assimilate into the local Dutch population and in the face of economic and political pressure, decided they needed to go elsewhere to found their own community.

So the Pilgrims—both separatists and others—planned to sail across the Atlantic in two vessels: the Speedwell (which had carried most of the Leiden congregation from Holland to England), and the Mayflower. When the two vessels set off, the Speedwell was found to be taking on water, and the ships went to Dartmouth, then Plymouth, for repairs. The Speedwell was abandoned, and the passengers were reshuffled onto one ship (the Mayflower), with some passengers being left behind.

The Mayflower left for the “New World” in September 1620 and anchored in Cape Cod two months later, where 41 men on the ship signed the Mayflower Compact. After scouting several sites, the ship landed in Plymouth harbor in December 1620 and soon began building Plymouth Colony.

The Mayflower had 102 passengers, as well as an estimated 30 crewmembers (some of whom were hired by passengers, and thus sometimes considered passengers). Only a handful of the crewmen were identified by name, and about half of them died in the first winter. But we know more about the passengers:

- 74 were male, 28 were female

- 69 were adults, plus 14 young adults and 19 children

- 45 died during the first winter

Only some of those 102 passengers had descendants (either in North America or Europe), and historians and genealogists have traced those descendants back to 26 families. Some of these families intermarried, making them somewhat trickier to trace.

How to Research Mayflower Descendants

To begin, organize the research you’ve already done, and highlight family lines with individuals born in the United States and Canada before the 18th century.

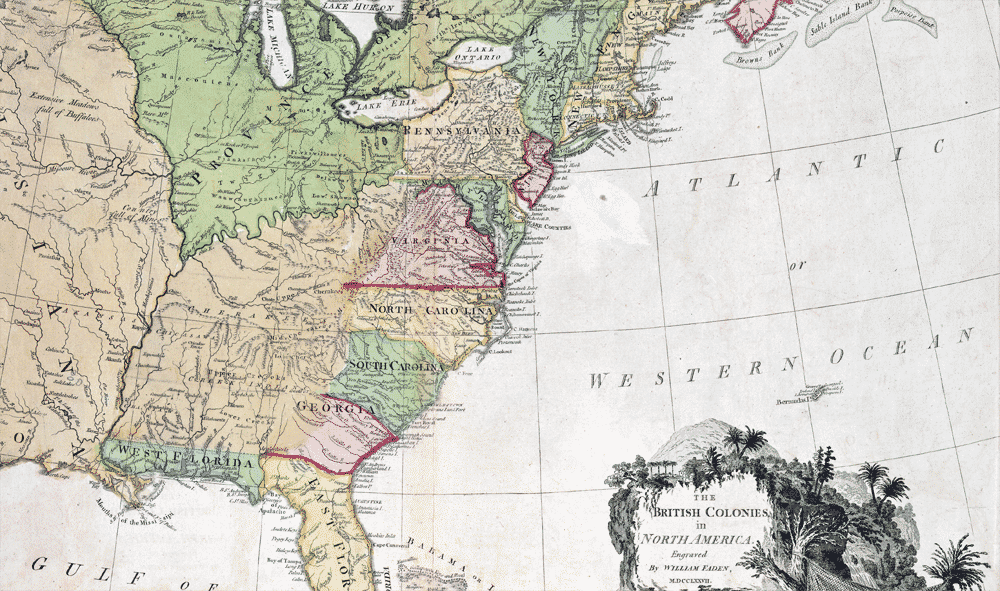

From there, you’ll have the most luck researching ancestors born before the Revolutionary War, specifically in one of several “hot” regions that have a high concentration of Mayflower descendants. While most Mayflower families remained in the Cape Cod area, some passengers’ children traveled to parts of Connecticut, New York and even Virginia. Their descendants followed common migration routes, settling elsewhere in the Northeast, the South, the Midwest and beyond.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Plymouth and Barnstable Counties in Massachusetts have the largest number of Mayflower descendants for a region. But Nova Scotia has a large concentration as well due to pre-Loyalist migration shortly before the American Revolution. Other hotspots in New England include Little Compton, R.I., southeastern Connecticut, and parts of Maine and New Jersey.

While it’s tempting to seize on a Mayflower lead you find in someone else’s family tree (or from family lore), resist the urge to assume that information is true. Most Americans know the Mayflower story and so want to trace their ancestry back to it, meaning some online trees and family stories contain more wishful thinking than evidence-based research.

In addition, you’ll want to avoid a number of Mayflower hoaxes—including family lines that are entirely fictional. Carefully research your family tree one generation at a time back through history, and consult only well-documented published genealogies.

Record Databases for Mayflower Ancestors

Published Genealogies: The Silver Books

Fortunately, the first century and a half of Mayflower descendants were documented in Mayflower Families Through Five Generations, a publication of the Mayflower Society that began in the 1970s and is commonly called the “Silver Books” project. In addition to the titular five generations, the Silver Books also document the births of sixth-generation children. More recent volumes even cover the sixth generation’s lives as adults, increasing the work’s scope.

The volumes begin with the “senior” generation, and deem any passengers who came over with their parents as “second generation.” Because ages of this senior generation vary widely (James Chilton, for example, was 64 years old, while Richard More was only 6), the sixth generation extends to the end of 17th century for some families and to the 19th century for others. (For context: Living Mayflower descendants today are 10 to 18 generations removed from passengers.)

You can view the Silver Books at various libraries, or purchase copies from the Mayflower Society or resellers like Amazon. And, thanks to a partnership with AmericanAncestors.org, you can view a fully searchable collection of fifth-generation descendants. Use these entries to determine if any of your documented ancestors are among established Mayflower descendants. Note: The database does not include the George Soule volumes of Mayflower Families in Progress, nor the genealogies of John Howland published by Picton Press.

Mayflower Society Applications

AmericanAncestors.org has also released a collection that picks up where the Silver Books leave off: Mayflower Society applications, from 1897 to present. (Note that documents from applicants less than 100 years old are withheld for privacy.)

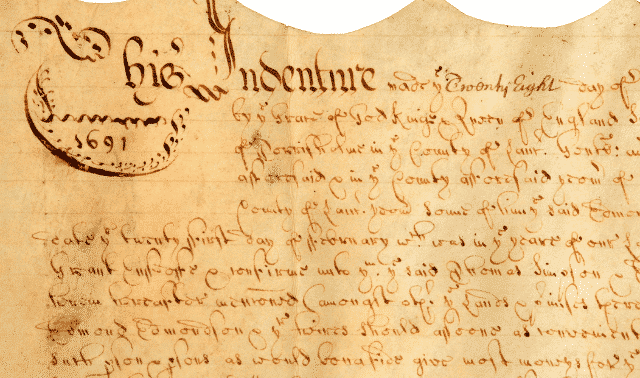

These early applications outline the line of descent from the passenger down to the applicant, containing birth, death and marriage dates and places for each generation and their spouse (plus references for supporting documentation, itemized by generation). Over time, standards for applying to the Mayflower Society became more stringent, with documentation on applications today being for each given vital event.

AmericanAncestTREES

In addition, AmericanAncestors.org has created an online family tree for each Mayflower passenger. Through the AmericanAncesTREES tool, you can view the trees—which include all deceased individuals from the Mayflower Society applications mentioned above—up through the 21st century. View an individual’s tree by scrolling down on an applicant’s results page and selecting his or her name. Learn more about AmericanAncestors.org’s Mayflower collections.

For example, my own Mayflower Society application, approved in 2010, is not viewable in the above searchable records collection for privacy reasons. However, I can follow the tree for John Billington (a Mayflower passenger) all the way down to my grandfather, Willard Alton Challender (1913–1986). The entry for my grandfather includes all the documentation I provided in my application. Though you’ll still want to review any resources and details you find in these trees, this collection can save you valuable research time.

Once your research connects with the information in the collection or AncesTREE, locate at least one source (preferably an original record) that links one generation to another, all the way back to the Mayflower passenger. This will create the skeleton of your Mayflower lineage.

Vital Records and Other Documents

Next, fill in the holes by locating records of each additional vital event (birth, marriage, death) for each generation of your ancestor and their spouse. While these records are usually quite detailed, you may encounter state-level privacy laws that limit access to them.

In addition, some states and localities (particularly in the 18th century) may not have had recordkeeping sufficient to prove family lines. In those cases, you might need to build a proof argument using indirect evidence from other records (or consult a published piece of research, such as a journal article) to prove your ancestors’ parent-child relationships.

For example, my own Mayflower descendant (at the eighth generation) traveled from New Hampshire through Pennsylvania to western New York state in the early 19th century. But without direct vital records, my research seemed to hit a dead end. I had to construct a 20-page analysis that utilized state census records, town school lists, Civil War pensions, and more to find the information I needed.

But by publishing that article, I not only established the parents of my fourth great-grandmother and their relationship to John Billington, but also identified six of her seven siblings and their children. This, in turn, added more scholarship to these highly families—should their descendants ever be interested in this part of their ancestry.

While finding a Mayflower ancestor is sometimes fairly straightforward (if they stayed in New England), or more complicated (if your ancestors continued west, north, or south), great scholarship and online resources can help in your research. Learning about these distant ancestors, the choices they made, and the lives of their descendants, allows for a greater understanding of Colonial American history.

A version of this article appeared in the November/December 2020 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT