Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

For more than 100 years, mystery books have ignited a love for problem-solving in children while also introducing them to the basics of genealogy research. An army of writers under pseudonyms penned popular series such as Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys, injecting their stories with key skills used by family historians every day.

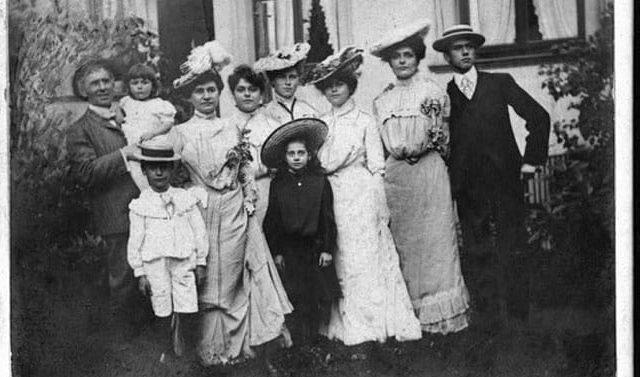

The parallels are striking. Mystery-solving sleuths like Nancy Drew interview persons of interest, document findings, and analyze evidence to come to conclusions. They tap many of the same records and institutions as do genealogists: photographs, maps, newspapers, libraries and cemeteries. Their adventures are story-based and sometimes involve travel, interacting with people from around the world, and learning about the deceased. And, like genealogists, sleuths and the mystery novels about them are universal and have ongoing, multi-generational appeal.

Generations of readers have found those resources and processes in the text of the classic Nancy Drew Mystery Stories:

- The Clue of the Black Keys (1951): Nancy describes working with a genealogist who traces family trees and has stacks of records.

- The Clue in the Old Album (1947): Nancy searches genealogy records herself as she tries to find mention of a fictional Henrietta Bostwick.

- The Clue of the Whistling Bagpipes (1964): Nancy researches her own maternal roots.

In fact, Nancy is a model for determined researchers. Though she drives a vintage speedy roadster and is a fashionable dresser (as compared to the modern genealogist, stereotypically working in pajamas), Nancy shares sage wisdom for today’s researchers.

Though much of the technology has changed since the first Drew title was published in 1930, the core research principles remain the same. Here are eight research strategies that genealogists can take away from the Nancy Drew series.

1. Search Cemeteries

Nancy visits cemeteries in at least three of her adventures, and any genealogist knows the importance of researching ancestral tombstones and burial grounds. In cemeteries, you’ll find not just death information, but also clues to your ancestor’s birth date, relationships, religious beliefs, economic status and more.

Fortunately, volunteers have uploaded cemetery information to websites such as BillionGraves, Find a Grave, Interment.net, and JewishGen’s Online Worldwide Burial Registry (JOWBR). There, you’ll find tombstone images, plus indexes to the genealogical data on them.

Though nothing replaces the experience of seeing your ancestor’s tombstone in person, all that data makes these websites crucial go-to’s, both before and after your trip to the cemetery. (Or they can be a nice substitute, if health, distance or money keeps you from visiting in person.)

“Is something missing?” Nancy asked. “Records. My ancestors’ records.”

Secret of the Forgotten City (1975)

Search each digitized cemetery collection individually; content can vary between the sites, so you don’t want to rely on only one. Volunteers don’t all visit the same locations or record the material in the same way. For example, names and dates on Jewish tombstones found at Find a Grave or BillionGraves might not be translated from Hebrew into English, as they are on JOWBR.

You can also go “old-school” and contact a cemetery office or local historical society for more information. Officials there might add information about other relatives buried nearby, the owner of the plot, or any municipal death certificates on file. Remember to check back for updates.

2. Study Historical Newspapers

In Mystery of the Glowing Eye (1974), Nancy used a newspaper file—back then, researchers had access only to physical copies of newspapers. And those who enjoy the smell and feel of aged, hard-copy clippings can still find them in the collections of local history libraries.

But technology has simplified access to obituaries, probate notices, and articles containing the names of ancestors. More newspapers continue to be digitized and made available on a variety of free and commercial websites.

The free Ancestor Hunt blog, compiled by Kenneth Marks, makes finding digitized newspapers easy, with a directory of US and Canadian newspapers that’s organized by state or specialty (such as ethnicity, language or publishing institution).

Another valuable free resource is the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America website. The database covers a wide swath of the United States’ historical newspapers, dating from 1789 to 1963. Chronicling America hosts many digitized papers on its site, but has also compiled the U.S. Newspaper Directory, a list of all known newspapers published in the country (regardless of if and where they’ve been digitized).

If you can’t find a digitized publication at either of the two above resources, consider commercial websites. Newspapers.com and GenealogyBank are the two most prominent with historical newspapers, but you can also find newspapers at Ancestry.com, MyHeritage, NewspaperArchive.com and (through your library’s subscription) ProQuest.

3. Explore Maps

By studying maps in The Clue of the Broken Locket (1934), Nancy was able to conclude that Pudding Stone Lake and Misty Lake were actually the same place. Identifying and locating places that are no longer around or that have changed names can be a challenge in any time period, and maps can help you solve those mysteries.

Spelling or transliteration errors, the use of multiple languages, or identical names in different locations add complications. But researchers can take advantage of web-based historical map collections such as:

- The David Rumsey Map Collection, in conjunction with Stanford University, began more than 30 years ago and now contains more than 150,000 digital maps. The collection has tens of thousands of downloadable historical maps, including rare maps from the 16th through 21st century.

- Maplandia hosts the Google Maps World Gazetteer, a searchable database of more than 2 million place names based on Google Maps. You can also browse by region.

- Ebay isn’t just for bidding on Nancy Drew collectibles! You can browse and bid on historical maps and reproductions.

- Mapire, the result of a collaboration between archives and libraries from several countries, specializes in 19th-century maps of Europe. Here, you’ll find European military surveys, plus Habsburg cadastral maps.

- Moll’s Historical Map Collection was assembled in the 1740s and 1750s by the German diplomat Bernhard Paul Moll. The collection includes 12,000 graphical representations of cities and landscapes in Central Europe.

- Map Geeks include free maps of several countries, cities and regions.

- Old Maps Online provides free access to indexes of 400,000 maps. You can even upload your own maps to the site’s collection.

4. Research Buildings with Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps

Maps showing political boundaries and military surveys aren’t the only documents to peruse. You can also channel your inner Nancy Drew by studying Sanborn fire insurance maps. These detailed maps were created by the Sanborn Map Co. between 1867 and 1977 to assess ask for fires, and they document more than 12,000 US cities and towns.

In addition to scale drawings of locations, they also contain street names, property boundaries and building materials, and locations of schools and houses of worship—particularly useful for properties or neighborhoods that no longer exist.

The University of California, Berkeley details where you can find these treasure maps both online and offline, and The Library of Congress Geography & Map Division has a goal to digitize them all.

5. Visit Public Libraries

Nancy made frequent trips to the library—as did many of her readers, who learned about her adventures from the books they borrowed there. But you needn’t despair if distance (or a pandemic) keeps you from visiting libraries in person: Nearly all public library districts have an online presence and offer interlibrary loan options. Better yet, many also provide card holders with access to subscription services like Ancestry.com’s Library Edition or ProQuest.

The largest public library in the United States is the Library of Congress, which (in addition to large collections of newspapers and Sanborn maps) also offers a comprehensive catalog of US local histories that you can borrow or search online. Its Prints & Photographs Online Catalog alone contains 1.2 million digital images; the full collection contains more than 14 million items.

Keep in mind that local public libraries may contain material from a broader regional area. The Denver Public Library Digital Collections, for example, include more than 100,000 photographs chronicling the people, places and events that shaped the settlement and growth of the whole Western United States. Likewise, the New York Public Library contains maps and material far outside of the Big Apple.

Another resource is the Digital Public Library of America, which is online, free and open to all—no need for a library card, subscription or even registration. The Family Research Guide to DPLA links to areas of interest for genealogists, including family photographs, family Bibles, local maps, military records, oral histories and personal letters. And, when working with DPLA materials, the useful “Cite this Item” feature provides full citations for a resource, in multiple formats.

Finally, although so much is online these days, Nancy Drew also reminds us not to forget the many treasures waiting to be found offline. So sometimes, you’ll need to visit libraries, archives, and historical societies in person—just like in 1930!

6. Read Books

In a similar way, family history detectives can take advantage of online book databases that Nancy Drew could never have even dreamed of. The cost of purchasing books can really add up, so accessing genealogical texts on free sites can be a huge windfall for researchers.

Google Books boasts the world’s most comprehensive index to millions of full-text books. Some of the collection’s out-of-copyright and public-domain books with genealogical value include wills, school census records, compiled early naturalization records, land deeds and community histories. You can also find foreign-language books, including those in Hebrew and Cyrillic character sets.

The Internet Archive is another nonprofit digital library of sorts, offering free access to books. Among the browsable results are rare books and foreign-language genealogy gems not found elsewhere such as The Census of The Jewish Population in The South Western Region of Russia in 1765–1791.

FamilySearch has tens of thousands of digitized books in its collection. In fact, the FamilySearch Digital Library searches for digitized genealogy and family history books from many major genealogy libraries, including its own Family History Library as well as the Allen County (Ind.) Public Library, Brigham Young University Library, Houston Public Library and Midwest Genealogy Center.

And although not focused specifically on books, ArchiveGrid provides access to more than 5 million detailed archival collection descriptions for materials held by libraries, archives, museums and historical societies around the world. Search for documents, personal papers, family histories and other materials.

7. Translate Foreign-Language Resources

Nancy Drew’s adventures have been published in dozens of languages, and the character herself has traveled to six of the seven continents. (The Hardy Boys beat her to the seventh: Antarctica.) So even navigating tricky foreign-language resources and websites won’t seem like so much of a challenge for the Nancy-trained researcher.

Many research institutions, such as The State Archival Service of Ukraine, The German Federal Archives, and The National Archives of Japan, have already made their websites accessible to English speakers by creating English versions. Look to the upper-right corners of landing pages on these and other international websites for an icon that indicates language options. An EN likely signifies English, as does a US or UK flag.

When a site doesn’t offer a translation, you can open the page using the Google Chrome browser to access a Google Translated version. Google’s free service instantly translates words, phrases and web pages between English and one of more than 100 languages. Those using a browser other than Chrome can visit Google Translate, then paste the URL with Detect Language selected. Click the resulting URL to access a version of the page in your selected language.

One-Step Webpages by Stephen P. Morse is another free resource that provides tools for dealing with foreign languages. Here, you’ll find links to resources that translate (or transliterate) text in print or cursive letters between languages with different character sets, such as Russian, German, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, Japanese, and Chinese. From Morse’s site, you can also decipher Jewish calendar dates and convert Roman numerals.

You can also study genealogical word lists to better acquaint yourself with words likely to come up in records. Family Tree Magazine has such lists for German terms, and you can find word lists for a variety of languages at the FamilySearch Research Wiki.

Looking for foreign-language books? Search WorldCat, an online listing of collections from more than 10,000 libraries across the world. Search for books by title, subject or keywords such as surnames or localities. And under Advanced Search, you can filter results by language of original publication. You can potentially borrow search results through interlbrary loan, or request them from the institution directly via email. (Note: Some libraries might charge a fee.)

8. Broaden Your Search to Include Less-Traditional Sources

While most genealogy is done using paper documents and their digital counterparts, researchers have to use whatever clues are in front of them.

Keeping an open mind about potential research leads was integral in The Clue in the Crossword Cipher (1967), when Nancy notices knotted strings of various colors called a quipu. Though less-observant researchers may have disregarded them, Nancy knew quipu were important to the Incas, who didn’t have a written language and so kept records using quipu. The number of knots in a quipu indicated how many wives and children a king had.

With that in mind, genealogists must study the cultural history of a community for innovative ways to describe relationships or the hierarchy of families. A terrific example would be how tattoos convey family and tribal history in the Polynesian islands.

Fabric pieces, such as quilts and wimples, are another often-overlooked source of family information, particularly about relationships, religion and place of origin. According to Sunny Jane Morton:

Women often made quilts to mark events or anniversaries; they might have monograms, names or dates. Passed down from generation to generation, quilts become intimate parts of a family’s history.

You can uncover more details by having a quilt appraised. Through that process, you might learn what year the style was popular (and, thus, what year it may have been made), plus clues about symbols used in the quilt or its intended function.

Wimples, decorative garments in the form of a long sash made from a baby’s swaddling cloth, are also often adorned with family names, dates and places. And because the cloth was used in several major life events, you may find it well-preserved. In pre-Holocaust Eastern Europe (particularly in German-speaking areas), for example, the wimple was made up of fabric used to swaddle an infant at his circumcision. Then, the wimple would be used to bind the Torah at the child’s bar mitzvah, then in his wedding chuppah.

Likewise, samplers (small pieces of hand-embroidered cloth) featured designs that often incorporating the details of a family lineage.

Nancy Drew Today

2020 marked the 90th anniversary of the Nancy Drew Mystery Series debut, and Nancy continues to inspire. We can easily imagine how quickly Nancy would solve those Depression- and wartime-era mysteries with the cutting-edge tools available to genealogists today. Relevant in a modern way thanks to The CW Network’s “Nancy Drew” TV show, Nancy and her friends integrate modern-day mystery-solving techniques using the internet, cell phones, recording devices and DNA.

You know you’re clues-obsessed when you can’t imagine a vacation without a mystery to solve.

The Mystery of the Brass-Bound Trunk (1940)

Popular around the world, Nancy’s stories are sometimes directly translated into other languages. Elsewhere, book titles remain the same, but the content changes for cultural reasons.

And Nancy’s name varies from place to place—just (unfortunately) like in genealogy. In German, Nancy is a law student named Susanne Langen. In France, Turkey and Vietnam, Nancy is called Alice. In Sweden, she is Kitty Drew; in Finland, Paula. And in Norway, Nancy is simply “Miss Detective.”

And with her global scope, Nancy Drew brings new perspectives to her American readers. Her books teach valuable cultural lessons to US audiences, such as introducing a language rarely spoken in America like Sinhala from Sri Lanka, or explaining how Hebrew and Arabic texts are read from right to left (rather than from left to right, like many Western languages). Like genealogists, Nancy has a constant thirst for knowledge, as well as an awareness of diversity.

Last updated: August 2020

ADVERTISEMENT