Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Q: I’m trying to find out info about a Seneca Indian in Civil War service. Where do you recommend I look?

A: We seldom hear about American Indian participation in the Civil War, but up to 29,000 Native Americans served on either side. A Seneca lawyer and Union general, Ely S. Parker, was the military secretary for Ulysses S. Grant and actually drew up the articles of surrender signed by Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Courthouse. (The City of Alexandria, Va. website has more information on Parker.)

After the American Revolution and several treaties, most Senecas settled in what are now two tribes in western New York. The state archives has an index of Civil War soldiers from New York; you will also find useful information at the New York State Military Museum.

A third group of Senecas migrated to Ohio and were removed to the Indian Territory of present-day Oklahoma. Some of these tribe members served in the Union’s 2nd Oklahoma Regiment, Indian Home Guard. You can read about the Indian Home Guard and about Oklahoma’s role in the war at Family Search.

To learn more about Indians in the war, see the American Indians in the Civil War wiki page at Family Search. To see which regiment your ancestor served with, look him up at the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Database.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2017 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: I have the original diaries my great-grandfather kept during his Civil War service, along with documents including his enlistment and discharge papers. How can I find museums or other organizations that would be interested in preserving this collection intact?

A: Your best bet is probably a museum, archive or historical society in the area where your ancestor lived. To find institutions in that locality, try some of the following online resources.

The Council of State Archives maintains a detailed directory of state and territorial archivists and records managers online and a directory of links to state archives. You can also contact the council by writing Victoria Irons Walch, Executive Director, 308 E. Burlington St. #189, Iowa City, IA 52240, or calling (319) 338-0248.

The American Association of Museums has a searchable guide to its accredited members at, or you can write to the association at 1575 I St. NW, Suite 400, Washington, DC 20005, or call (202) 289-1818.

Search a directory of more than 4,500 historical societies in North America and more than 7,000 history museums.

There’s a clickable map linked to sites for state historical societies. Individual state historical societies often maintain directories of historical societies at the county level, such as this guide to Missouri or this for Wisconsin. You can browse an extensive list of local historical societies, organized by state.

State libraries might also be interested.

Since you have Civil War records specifically, you may also want to check the American Association for State and Local History’s list of contacts for the Civil War Sesquicentennial.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the November 2011 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: How do I learn more about a Civil War ancestor who was a prisoner of war?

A: If you haven’t already, obtain the ancestor’s compiled military service record (CMSR) from the National Archives. (You can view Confederate records and Union records or index cards online at the subscription site Fold3.com.) In addition to the standard “envelope,” the CMSR may also include an internal jacket of “personal papers,” such as any record of the soldier’s being a prisoner of war.

For specific prisoner of war records, consult the Archives’ record group 249, Records of the Commissary General of Prisoners. The 347 series in this group include records relating to the parole of federal prisoners, prisoners held in Confederate prisons including Andersonville (Ga.), Confederate prisoners of war held in Union prisons, and claims filed by Union prisoners of war. Information on Confederate POWs is also in record group 109 (National Archives microfilm publication M598); these records are available in 145 rolls of microfilm from the Family History Library (FHL). The FHL also has some records of specific prisons, lists of those paroled at particular locations, and memoirs of POWs.

If you think a Confederate ancestor died in a federal prison or military hospital in the North, check record group 92 (National Archives microfilm publication M918).

Subscription website Ancestry.com includes a searchable database of Civil War prisoner of war records. Among these are digitized versions of six microfilm rolls from record group 249 relating to Andersonville, all of record group 109 and the one roll of record group 92. You can search this collection here.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the November 2011 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: Today when soldiers are killed in action, the bodies are sent home for burial. I have an ancestor from New Hampshire who was killed in action in Virginia during the Civil War. Where were the bodies buried back then?

A: Typically, because of the magnitude of the carnage, the fallen from both sides were buried on or near the battlefield sites. Most of these graveyards are now national cemeteries, and this issue’s top 10 list of Civil War websites can help you find your ancestor in those graveyards.

The Department of Veterans Affairs’ site searches for those buried in VA national cemeteries across the country, including soldiers from the Civil War.

The National Park Service also manages 14 national cemeteries, all but one of which is related to a Civil War battlefield park, and the agency is working on listing all names of burials in these cemeteries on its Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System website.

Already up are data from written records of Poplar Grove National Cemetery at Petersburg National Battlefield, including images of the headstones. Poplar Grove is also indexed in the VA site, but if you don’t find an ancestor there who might have fallen at Petersburg, it’s worth double-checking at the Park Service site.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the May 2011 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: My ancestor got involved in the US Civil War even though he was from Nova Scotia, Canada. As a ship’s captain, he ran the Union blockade and was captured and died in a Yankee POW camp. How can I find his POW record?

A: Because he died while incarcerated, your ancestor should be in National Archives microfilm M918: Register of Confederate Soldiers, Sailors and Citizens Who Died in Federal Prisons and Military Hospitals in the North, 1861–1865 (one roll), available through the Family History Library. If not, you’ll have to turn to the much larger (145 rolls) Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, 1861-1865, which is National Archives microfilm M598.

Both of these record sets are part of subscription site Ancestry.com’s collection Civil War Prisoner of War Records, 1861–1865. Search this database by first and middle name, last name, side (Confederate or Union), film roll number or title, or keyword. Try the full title for roll M918 and check Exact to limit your search. If searching the name alone doesn’t help, use keywords such as Capt. or Citizen (because your ancestor wasn’t in the Confederate Navy), or Canada and uncheck the Exact restriction.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the May 2011 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: All I know is that my great-grandfather Joseph A. Harbison fought for the Union in the Civil War. He enlisted from Pennsylvania. How do I get information about him?

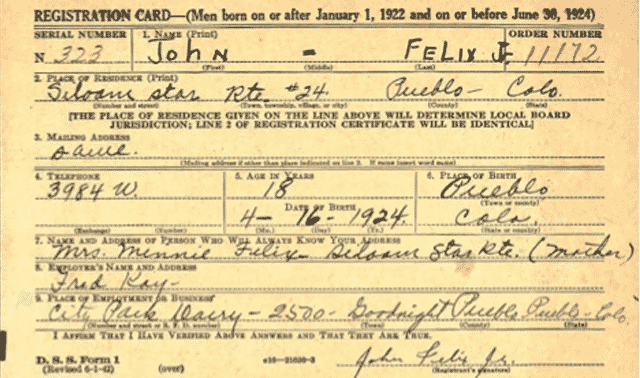

A:The National Park Service has given you a great place to start in its Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Database (CWSS). You can search for Union or Confederate soldiers and African-American Union sailors. Our search turned up a Joseph H. Harbison in the 11th Regiment, Pennsylvania Infantry. Is this your great-grandfather with an incorrect middle initial? Before making the call, you’ll want to consult this man’s service records. CWSS gives you the microfilm number you need to order copies (for a fee) of a service file from the National Archives and Records Administration’s (NARA) Order Online site.

In the CWSS search results, click on a unit name for details on when and where the unit was raised and the battles it fought, and how many members died from bullets and disease. Another way to confirm the Joseph we found is your great-grandfather: Check the 1860 US census for for other Joseph Harbisons in the counties where the Pennsylvania 11th was raised.

Your great-grandfather may have applied for a military pension. Look for the General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934, on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org. I found a Joseph Harbison who filed for a pension in Pennsylvania July 29, 1890 (his application number is 495309). Keep in mind this could be a different Joseph; request copies of the originals from NARA to be sure.

Answer provided by Diane Haddad

Q: I am trying to find information about the death of a Civil War soldier. I have his military records, and they say only that he died at Fort Pickering, Tenn. on Aug. 17, 1862. He was in the Battle of Shiloh, Siege of Corinth. I am interested in finding out if he died of disease or wounds. How do I go about this?

A: First, you need to know whether the soldier was in the Union or Confederate army, because available records differ somewhat. Since Fort Pickering (in Memphis) was in Union hands after June 1862, the ancestor may well have been a Union soldier. If his compiled service records do not give a cause of death, you could consult the following sources:

- published company or regimental history, which might suggest a timeline of events, including engagements and disease outbreaks within the unit

- widow’s pension file

- the National Archives records of Civil War hospitals and registers of deceased volunteer Civil War soldiers

Also consult U.S. Military Records: A Guide to Federal & State Sources, Colonial America to the Present by James C. Neagles (Ancestry), The Union: A Guide to Federal Archives Relating to the Civil War by Kenneth W. Munden and Henry Putney Beers (National Archives and Records Administration), and The Confederacy: A Guide to the Archives of Government of the Confederate States of America by Henry Beers (NARA), as well as other reference works.

Answer provided by Emily Anne Croom

Q: I have my ancestors’ Civil War service records from the National Archives and Records Administration. Do military records offered by some states contain different information? I’m wondering whether it’s worthwhile to check those records, too.

A: State archives’ Civil War collections often differ greatly from the Compiled Military Service Records (CMSRs) and pension files available from NARA.

States may hold soldiers’ letters, regimental histories, Civil War-era newspapers, Grand Army of the Republic post records, veterans’ cemetery indexes, soldiers’ home records and more. (Archives of formerly Confederate states also have pension records. Those aren’t at NARA because the federal government didn’t pay Confederate soldiers’ pensions.)

For example, the Ohio archives has correspondence to the state’s governor and adjutant general dating from 1859 through 1862 (series 147, volume 42). In May and June, 1862, Col. John W. Fuller and Maj. Z.S. Spaulding of the Ohio Volunteer Infantry 27th Regiment wrote Adjutant General C.W. Hill, describing their encampment and recommending various promotions.

Since state Civil War collections are so varied, I can’t say whether the information would be different from what’s in your ancestors’ CMSRs. But even if the state record doesn’t have previously unknown details, You’ll have new evidence of your ancestor’s presence at the place and time the record was created.

If my ancestor were in the Ohio 27th, I’d want to know whether his commanding officers had anything to say about him, and where he was in June, 1862. (You can browse abstracts of these letters, as well an index to Ohio prisoners at Andersonville and a guide to Civil War-related primary source collections, on the archives’ Web site.)

Start by searching your ancestral state archives’ online catalog for Civil War-era materials related to your ancestor, his regiment, or the county and town where he lived. Likely, you won’t know from the catalog listing whether the source mentions your ancestor, so you may have to visit the archives or contact an archivist for help.

You might be able to save yourself the trip by borrowing materials through interlibrary loan, ordering photocopies of documents or seeing if the Family History Library has microfilmed copies (which you can rent through a Family History Center).

Check local historical society and university libraries for Civil War collections, too.

Answer provided by Allison Dolan

Q: How do I trace an American Indian when all I have is the name the Army gave him when he became an Indian scout around the Civil War era?

A: You’re fortunate to have that English name for your ancestor. It will help you research backward, so you can learn your ancestor’s American Indian name and tribe.

Start by documenting your ancestor’s service as a Civil War Indian scout. American Indians served in volunteer and Union and Confederate Army units. The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System indexes 6.3 million service records for soldiers from both sides.

Most Civil War Indian scouts, though, weren’t traditional enlistees. Army generals hired scouts for their knowledge of area resources and geography, and their tracking and fighting skills. Despite their unconventional roles, Indian scouts are documented in Civil War and local histories, in claims filed with the government after the war, and later in correspondence of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

While much has been written about American Indians’ service in the Confederate Army, their Union service isn’t documented as well. Lists of Civil War scouts in published or online histories are valuable because they provide names and usually list tribal affiliations. Identifying your ancestor’s tribe will open a treasure trove of Bureau of Indian Affairs records — see the Guide to Records in the National Archives of the United States Relating to American Indians for details.

Like many family traditions, the story about your ancestor being an Army Indian scout may have become distorted over time. So don’t overlook the possibility that his service came later. Immediately after the Civil War, the US Army established a formal Indian Scout Service, and scouts were documented as regular enlistees. I’d suggest reading chapter 11 of the Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives of the United States, 3rd edition (National Archives and Records Administration), for an excellent introduction to federal American Indian records, including military records of American Indians and Indian scouts. You also could try the Native American Genealogical Sourcebook edited by Paula K. Byers (Gale Research, out of print), available at many libraries.

Answer provided by James W. Warren

A version of this article appeared in the August 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT