Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Not everyone who wished to come to America could afford it. The New World promised land, opportunity, and religious freedom sometimes not found in the Old. As a result, indentured servants were common in American settlements. Of the Mayflower’s 102 passengers, fourteen were servants. By working a set period of time, assuming that the servant would survive the experience, a person expected to better himself or herself.

There has been a renewed interest in indentured servants. Not well-heeled, servants were the working men, women, and children. Many people have no idea they are descended from indentured servants. Here are some tips to discover if your ancestor was one.

What is an indentured servant?

An indenture is a written contract between two parties. They are commonly used today. However, during the European migration to America, they were used to bind people’s servitude in some manner. These indentured servants would be bound to work for a specified timeframe. After their time was up, they would receive their freedom but also anything else agreed upon: a trade, land, money, even clothing. The master to whom the work was owed also had obligations. They were required to provide room, board, and other necessities for the indentured man or woman.

The indentured servant experience

In some cases, skilled labor was needed above raw labor. These indentured servants were shipped to the New World but had no master, per se. The servants’ contracts would be sold to colonists here for specific tasks needed.

On occasion natives indentured themselves. Other times, people were given a choice of prison or indentured servitude. An example is those who took part in the Battle of Dunbar in Scotland (1650). After the Scottish defeat, some of the Scots were sent to Lynn (Saugus) in the Massachusetts Bay Colony to work in the iron mine there as indentured servants. Sometimes children were indentured when they became fatherless or orphans. They would be placed in homes where they would be cared for and learn a vocation.

Did they have rights?

Unfortunately, not all of the experiences were good ones. The servant’s life might be full of abuse. But, since there was a legal contract involved, the servant had recourse though the court system. Sometimes abused servants took the law into their own hands or ran away. When apprehended, the servant was subject to the same courts to which he or she might have appealed. However, the more remote a plantation or settlement was, the more opportunity for abuse was possible. A tragic example can be found with the Majorcans, Turks, and others, who were under the thumb of Andrew Turnball in Florida.

The death of a master or mistress of the indentured servant might be a boon to the indentured servant. Depending of the disposition of the master or mistress, the servant might be released from their remaining time as specified in the indenture. Their service might also be transferred to another person or family member. In one New Hampshire instance, the servant received all of the tools of his master. Perhaps he was an apprentice?

Locating records

Online resources

When searching online in published books and records look for these keywords: apprentice (abbreviated “appr.”), servant (abbreviated “serv.”), indentured servant, maidservant, or manservant. People can be described as servants in court records or depositions.

Wills

Wills are also a good source if indentured time is still due to the testator. Local records might show that land was granted where before it was not.

Newspapers

Newspapers are another source where servants or apprentices might be named if they ran away. The benefit of having an advertisement for a runaway is that usually the age, complexion, hair (or wig) color, and stature, accompany other details. Also, when remaining contract time was sold, a description of the person was often given but perhaps not the individual’s name. However, this might help a researcher discover why a person is living in one town but has removed to another with a different family.

Case study: Finding an indentured servant ancestor on Ancestry.com

- Ancestry.com offers a “Virginia, Apprentice Index, 1640-1800,” which is cross referenced to Virginia records.

- Entering the last name of “Jones,” yields 18 results. I chose Solomon Jones, whose father was Richard Jones. Solomon was apprenticed on December 4, 1728, to learn how to be a cooper under John Wakefield.

- The cross reference is “Princess Anne County Minutes [book] 4, 1728-1737, [page] 7.”

- Jumping over to FamilySearch.org’s Catalog and looking for Princess Anne County the webpage shows that it merged with the city of Virginia Beach, which is the next stop.

- Under “Court records,” I find County Court minute books and processioners’ returns, 1709-1861.

- Drilling down, I find that Minute book 4, 1728-1737 is not listed! However, “Minute books, 1709-1717, 1728-1737, 1753-1762” are.

- Not giving up, I open the link for the Minute books for the given book and, digging through pages, Book 4 is found. As expected, page 7 has the following entry, which includes more detailed information than found in the index alone:

Ordered that Solomon Jones an orphan of Richard Jones Decd be bound to John wakefield who is to teach ye Said orphan to read the bible Distinctly to write a good Leadgable hand likewise the trade of a Cooper, that he Carry him to the clarks office & take Indentures to that purpose.

Other Ancestry.com search examples

Here are further examples of keyword searching books in Ancestry.com, using some of the keywords above:

- A search in New England Genealogical Dictionary of Maine and New Hampshire yielded over 200 men and women, who were identified as servants.

- A search for “servant” in All Scots in Georgia and the Deep South, 1735-1845 gives over 150 hits.

Indentured Servants Q&A

Q: How do you find records on indentured servants? I have no idea what the name of the ship was. All I know is that John and William Nolan went on a ship somewhere in Ireland to sell boiled eggs and stowed away until the ship left port and then a tanner paid for their fare. Any help would be appreciated.

A: An indentured servant was a person headed to colonial America who contracted or was “bound,” before departure, to a property owner in order to work as a servant for a specified time (average seven years), usually in exchange for ship’s passage and for minimal shelter, food and clothing. A “redemptioner” was another type of indentured servant who had not contracted before departure, but whose servant contract was sold by the ship’s captain if he or she could not repay passage within a designated period (such as two weeks) after arrival in colonial America.

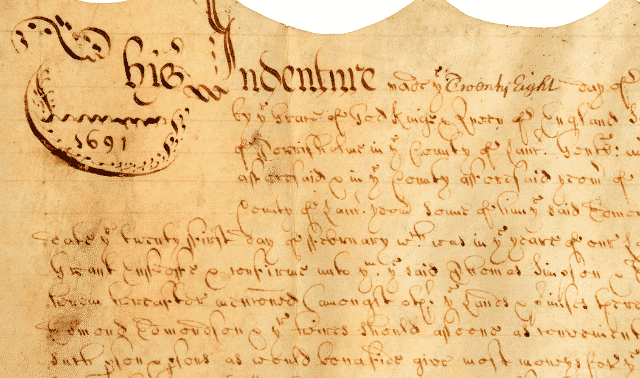

There are several published works that list arrivals of colonial indentured servants and redemptioners, such as Peter Wilson Coldham’s The Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage, 1614-1775 and Emigrants in Chains, 1607-1776. Another would be Frances McDonnell’s Emigrants from Ireland to America, 1735-1743. Indentures were often recorded in official records of towns and county courthouses. There may be a separate volume for indentures, apprentices, and servants, or these records might be included within deed books.

Answer provided by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

Q: My ancestor Patience Breeden was an indentured servant of John Oldham in Virginia. She gave birth to a son, Bryan, about 1701. Court records state that Patience would be indentured an additional year, and Oldham would keep Bryan until he was 21. I suspect that Oldham was Bryan’s father. How can I find out for sure, and learn whatever happened to Patience?

A: An indentured servant entered into a contract for a specific number of years, in exchange for his or her passage to America. This custom persisted into the 19th century, providing newcomers with food, shelter and clothing, in exchange for work and training in new trades. If the immigrant didn’t meet the terms of the agreement, though (often it was more like slave labor with minimal freedom), he risked fines, imprisonment, physical punishment or additional years of indenture. Indenture contracts generally give the name of the servant, his or her parents and the master; the location and length of indenture; and, in some cases, immigration information.

Records of indenture can be hard to locate because they’re held in a variety of places: Some, such as the ones you found, are part of court records; others are in collections of the master’s personal papers. Published indexes of indenture papers, such as these books and those on the Virtual Jamestown website (which covers late 17th- and early 18th-century indenture contracts from English registers in London, Middlesex and Bristol), can help researchers find these records. Genealogical firm Price and Associates also has an indentured servant database. Additionally, old newspapers may carry wanted notices for runaway servants.

Patience’s court records mention her child because her pregnancy extended her term of indenture. Establishing paternity may be difficult or impossible unless you can find a document, such as an additional indenture contract for Bryan, in which Oldham claims to be his father. Since Patience gave birth out of wedlock, you could look for a bastardy or fornication case against her.

I would start by checking local and state archives, such as the Library of Virginia, for John Oldham’s papers, then searching court records in hope that the documentation exists. It may not, though, so be prepared for disappointment.

Answer provided by Maureen Taylor

Q: My fifth-great-grandfather Nathaniel Tenpenny was convicted of a crime in England in 1764 and sentenced to seven years of indentured servitude in America. He was transported aboard the Tryal the same year. He’s in the 1790 Rowan County, NC, census with his family, but I haven’t been able to find out their names or anything else about him.

A: An indentured servant was “bound” to a property owner in exchange for passage to America. Many people indentured themselves. Your ancestor was part of a popular criminal justice trend in England: Punishment by “transportation,” or exile to work in America (after the Revolutionary War, Australia became the primary destination).

After England passed the Transportation Act in 1718, courts there sent approximately 60,000 convicts—called “the King’s passengers”—to America.

It sounds like you found the information on Nathaniel Tenpenny’s conviction for stealing tools online at The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, London, 1674 to 1834. That site has accounts of more than 100,000 trials at London’s central criminal court.

Look for your ancestor’s name in two books by Peter Wilson Coldham: The Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage, 1614-1775 and Emigrants in Chains, 1607-1776. You may learn the port where his ship arrived and other details, giving you a starting point.

There’s a good chance your ancestor served his sentence in Maryland or Virginia. According to a 2004 NPR report, 90 percent of the “King’s passengers” served their sentences in Maryland and Virginia.

Laws governed indentured servitude (servants who tried to run away or became pregnant, for example, might have their contracts extended), so look for contracts and other documents among court records where your ancestor served. If you learn whom he was indentured to, check the local historical society and university archives for collections of personal papers—they may mention Nathaniel.

To narrow Nathaniel’s place of service, research him backward from his most recent known location—North Carolina in the 1790 census. Look for Colonial censuses, land and tax records. Presumably Nathaniel would’ve been released in the early 1770s. Could he have returned to England temporarily? Stayed in America and fought in the Revolutionary War?

Look for his will, too, which would likely give the names of his children and wife.

Answer provided by Allison Dolan

Apprentices and indentured servants in America

Among the oldest occupational records you’re likely to find are those for two kinds of employment almost unheard of today: apprenticeships, in which a young person was bound to a master to learn a trade, and indentured servitude, in which a person was committed to working off a debt, such as payment for passage to America. The two often overlap, and in Colonial America the agreement apprenticing a youth was called an indenture. These documents are valuable for genealogy because they had to be signed by the apprentice’s parent or guardian. Most apprentices were teenage boys, and they were obligated to work at their trade until age 21. The term of an apprenticeship can be used to estimate an apprenticed ancestor’s age, by subtracting the term from 21.

Typically, apprenticeship records were made at the local level, but many of these documents have since migrated into state archives and historical societies. If you have English ancestors, you might be able to use apprenticeship records to trace your kin back to the old country; the British National Archives has a helpful guide to these resources.

For early American ancestors, the FHL has collections of apprenticeship documents from Pennsylvania and Virginia. Ancestry.com offers a database of more than 8,000 Virginia apprentices from 1623 to 1800. Indenture records also can overlap with passenger records, as the most common type of indenture was payment for passage to America. State and local archives may hold indenture records, although these can take a bit of digging to find. The Pennsylvania State Archives, for instance, has two boxes labeled “Records of the Proprietary Government, Provincial Council, 1682 1776 — Miscellaneous Papers, 1664-1775,” among which a dedicated researcher could uncover the Oct. 31, 1765, agreement binding one Charles Carroll of Maryland to Richard McCallister.

Written by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the April 2005 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Research resources

The National Society Descendants of Colonial Indentured Servants was formed in 2019 to identify indentured (not apprenticed) ancestors. It publishes a yearly newsletter, The Passage. Here are several resources which were used to prove a member’s ancestor was an indentured servant. (You can find a complete resource list here.)

Online resources

National

British National Archives

Family History Research Guides

Colonial Williamsburg

Lusty Beggars, Dissolute Women, Sorners, Gypsies, and Vagabonds for Virginia

History Detectives

Indentured Servants in the U.S.

Library of Congress

Immigrant Arrivals: A Guide To Published Sources

Price Genealogy

Immigrant Servants Database

Virtual Jamestown

England to New World: Registers of Servants Sent to Foreign Plantations, 1654 – 1686 (from Bristol, Middlesex, London)

By State

Maine/Massachusetts/New Hampshire

The Dunbar Diaspora: Background to the Battle of Dunbar, and the Aftermath of the Battle

Maryland

The New Early Settlers of Maryland (use servant as a keyword in the search)

Hampton: Stories of the Indentured Servants

Understanding Maryland Records: Indentures Servants

North Carolina

Slavery and Servitude in the Colony of North Carolina

Pennsylvania (Chester County)

Indentured Servants Complaints 1700-1855

Books

White Servitude in the Colony of Virginia by James Curtis Ballagh

Bonded Passengers to America, 9 volumes, by Peter Wilson Coldham

The Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage, 1614-1775 by Peter Wilson Coldham

Scots in Georgia and the Deep South, 1735-1845 by David Dobson

Records of Indentured Servants & of Certificates for Land: Northumberland County, Virginia, 1650-1795 by Washington Preston Haynie

Servants and Servitude by Russell M. Lawson

Runaways of Colonial New Jersey: Indentured Servants, Slaves, Deserters, and Prisoners, 1720-1781 by Richard B. Marrin

To Serve Well and Faithfully: Labor and Indentured Servants in Pennsylvania, 1682-1800 by Sharon V. Salinger

Emigrants to America: Indentured Servants Recruited in London, 1718-1733 by John Wareing

Indentured Migration and the Servant Trade from London to America, 1618-1718: ‘There is Great Want of Servants’ by John Wareing

Titles by Joseph Lee Boyle (various)

Last updated, April 2021.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to Amazon and affiliated websites.

ADVERTISEMENT