Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Imagine receiving a family photograph album with a handwritten index! In Rita Werner’s case, this gift was a mixed blessing. All but three of the original tintype photographs had been removed from the album, and Werner doesn’t know who compiled the index. But Werner’s mother recently found an envelope of tintypes she believes are the missing photographs. Now mother and daughter have an opportunity to identify the pictures and put them back in the book where they belong.

It’s a typical late-19th-century album of deeply embossed leather with white glass “buttons” on each corner and two clasps holding it together. Such albums resembled family Bibles and often remained on display for visitors. This particular album has “F. Heppenheimer, 22 N. William St., NY” printed on the cover page. The 1869 New York City directory lists a lithographer named Frederick Heppenheimer with a business at that address. To date the album, Werner must search city directories to determine the exact years Heppenheimer worked at North William Street.

Next, Werner must date the photographs to see if they are about the same age as the album. Tintypes gained popularity in 1856 and are still available today. Also known as ferrotypes, they were made on sheets of iron that ranged in size from “gems” (¾x1 inches) to whole plates (6×8½ inches). Dating the images and comparing that information to genealogical data is the best way to determine if this collection of individual tintypes was part of the album.

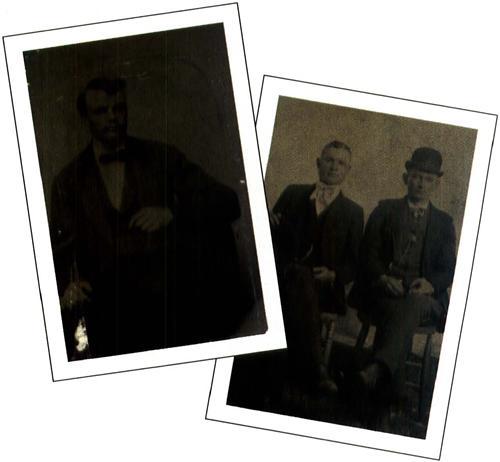

Many of the names in the index are relatives, but some names Werner doesn’t recognize. This is not unusual, as photo albums often contained images of both family and friends. A loose photograph of two young men is one of the images that Werner suspects came from the album. A notation in the index refers to a portrait of “Mr. Welch and T. Connor.” This is the only tintype of two individuals, so it’s probably the right photograph. A Thomas R. Connor, Werner’s great-great grandfather, emigrated from Ireland in 1870 and was married in Utica, NY, in 1872. He and his bride moved to northern Illinois before the birth of their first child, Thomas E. Connor, in Grundy County, Ill., in April 1873.

To which T. Connor does the index refer — Thomas R. Connor (1848-1934) or his son Thomas E. Connor (born 1873)? From other family images, it’s clear that the son bears a strong resemblance to his father. Yet, comparing this photograph to a tintype of Thomas R. Connor that was taken from a family Bible, you can see that the mouths of the men look very different.

Their clothing also helps date the images. In the Bible photograph, Thomas R. Connor wears a loose suit jacket with a wide collar, a double-breasted vest and a bow tie. This clothing places the photograph in the late 1860s to 1870. The portrait of the two young men was taken later, perhaps in the 1890s, as revealed by the shapes of their jackets, vests and hats, as well as their short-cropped haircuts.

Several relatives who saw the photograph of the young men identified the man on the left as the son. Photographs of the Connor men taken in the 1930s verify this identification.

There are plenty of identification possibilities for “Mr. Welch.” Narrowing down the suspects involves discovering a relationship between the two men — as friends, coworkers, members of the same organization, neighbors or even fellow immigrants. Census records, city directories and vital records might provide clues to his identity.

Without contrary evidence, the photograph of the two men quite possibly belongs in the album, especially because it is the only loose photograph that fits the index description. With one of the loose photographs identified, the owners may be able to re-create the album one photograph at a time.

There’s a lesson to be learned here. If you own a photograph album and are curious about writing on the back of the pictures, take time to photocopy the pages as they appear before you remove images. With albums, it’s best to proceed cautiously. Even removing images to prevent damage due to paper quality is not always necessary — most of the damage has already occurred. Why not retain the original order and read the story as your ancestors laid it out on the page?

From the April 2003 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT