Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

You can learn a lot about people’s lives by strolling through their neighborhoods. Where’s the nearest school, church or theater? How are the buildings and streets maintained? Do family or good friends live nearby? What about others who share their culture, tastes or values? Where can they shop? How far are they from work and how do they get there?

Neighborhoods of yesterday also reveal these kinds of details about your ancestors and offer clues for further family research. Nearby institutions or organizations may have kept records that include your family. Old property lines or the former residents’ ethnicity may solve puzzling genealogical questions. Even better, some of those old neighbors may turn out to be kin.

Using family history blueprints

Though the people, homes, landscapes and businesses of your ancestors’ day may be gone or changed, you can virtually reconstruct them. Old documents, maps, photos and stories will provide your blueprints and construction materials.

When I mentally strolled through the neighborhood of my husband’s ancestor Andrew O’Hotnicky, I realized that his family spent most of their lives within the two-block radius of a tiny but vibrant ethnic enclave—and the in-laws I was hunting were right there, too. But before you break ground on your own building project, we’ll show you how to find your relatives’ addresses and where they’re located today. Then we’ll demonstrate how to put it all together with records, photos and stories in a step-by-step example centering on the O’Hotnicky’s. Let construction begin.

Addressing the past

First, you’ll need to identify a site for your building project. For a historical neighborhood, that means knowing exactly where it was. Of course, old records won’t give you GPS coordinates, and even full street addresses and ZIP codes are relatively modern inventions.

Many houses were numbered before the 20th century, but US mailing addresses were simply comprised of a name, town and state. Residents picked up their mail at local post offices. Travelers followed maps to their general destinations, then asked locals to point them to a home or business. It worked back then, when there were fewer people in most places and more people knew who their neighbors were.

Home mail delivery began in the Civil War era for some Northern cities and gradually spread. That’s why, during the late 1800s and early 1900s, many older cities changed and standardized street names and house numbering systems. By 1902, home mail delivery finally reached suburban and rural residents, some of the latter via alternative mail carriers along designated rural or “star” routes. ZIP codes came along only in 1963, and ZIP+4 codes in the 1980s.

So it can be difficult to determine a home’s location from an older document. You’ll likely need to follow location clues forward through censuses, deeds, maps and other resources. As later documents more specifically describe places, you’ll be able to pinpoint the site where you’re trying to rebuild. You’ll see this principle in action below, as I trace a family’s residence from an undefined house number on a street to its (almost) exact location.

Making sense of census addresses

The census is often the first place you’ll find clues about where a family lived. Initially, census-takers identified residents only by state and county, township, town or city. Enumerators did work within geographically defined areas called enumeration districts (EDs), noted at the top of each sheet, which can help you narrow an ancestor’s location. You can find tools for researching enumeration district maps and boundaries from 1880 forward at Steve Morse One-Step Webpages. The National Archives has descriptions of each ED’s boundaries for the 1830 to 1890 and 1910 to 1950, as well as ED maps for 1900 to 1940, on microfilm. The maps are digitized on the free FamilySearch site.

The 1880 US census was the first to record street names and house numbers. The street name is written vertically along the left edge of the page, and the house number is in the next column. (Don’t confuse the house number with the “dwelling house” and family numbers, which numbered each house and family in order of enumeration.) The 1890 census, now mostly destroyed, was recorded on family schedules with street names and house numbers at the top. From 1900 on, censuses include street names and house numbers on the left edge.

My husband’s ancestors and newlyweds Andrew and Rose O’Hotnicky first appear as a couple in the 1910 census, residing on Jones Street in the northeastern Pennsylvania town of Olyphant. In 1920 and 1930, their growing family lived at 117 West Grant Street in Olyphant.

The 1930 census includes a detail that caught my eye. Usually, homeownership status is noted only for the heads of household. But that year, Andrew’s widowed mother Caroline lived with the family. She’s listed as owning her home in the same household where her son, the head of household, is a renter.

According to the census instructions, Caroline’s homeownership was to be noted only if she lived at the property she owned. If the enumerator followed those instructions, then Andrew and Rose were renting their home from his mother. Their rent was $20 a month, 20 percent lower than three neighbors paid. Were they getting a family discount?

That census page offered other insights into their surroundings. Most men were miners, though Andrew drove a fire truck. Neighbors were born in Poland, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Galicia. Nuns of Czech descent lived around the corner. I wanted to flesh out a meaningful story from these details. First, I sought a deed to the West Grant Street house to confirm Caroline’s ownership and when she acquired it.

Drilling into deed descriptions

Deeds are legal documents that record the description of properties and their transfer from one owner to the next. Generally, you can find them in county offices where the property is located (or in town offices, in New England). Some are imaged on microfilm, with copies at a historical society or local library, and fewer are digitized and/or indexed online. Most of the time, you’ll need to get them from the county recorder’s office. Because most deed research is more complicated than a simple photocopy request, you may need to hire a local researcher or go there yourself. (Get our in-depth guide to researching deeds at <shopfamilytree.com/research-strategies-land-deeds-u4009>.)

Accessing deeds works differently at different recorders’ offices. The deeds themselves are usually in large, chronological volumes. To find the correct volume and page number, you’ll hope indexes exist for grantees (buyers) and grantors (sellers). If you don’t know when a property was purchased—or exactly under whose name—scan all the indexes looking for familiar surnames. If indexes don’t exist or don’t cover the places and time periods you need, you’ll have to know the specific location of the property. This usually means finding the subdivision name and lot number assigned when the area was surveyed or developed (not the same as the house number).

First, I found an 1892 purchase by Caroline and her husband Andreas for Lot 10 on Jones Street, with no house number. This wasn’t 117 West Grant Street, but Andrew and Rose did live on Jones Street in 1910. I traced the deed forward to the next sale of that property, in 1945. That deed explained that Jones Street had been renamed Grant Street, but still didn’t give me a house number. Some cities, especially major ones, have published guides to street and address changes, or included this information in city directories published when the changes occurred. Ask at historical and genealogical societies. These sources will allow you to see what’s on your ancestor’s property today.

That 1945 deed also revealed other important facts. The property changed hands within the family between 1892 and 1945. At Caroline’s husband’s death in 1898, it passed to her sole ownership. At her death in 1937, it passed to all the children jointly. The deed stated exact death dates for both parents and listed all the children with their spouses and residences. Researching the property was helping me extend the family tree. It’s not unusual to find family information in property transactions. After all, property is often inherited, sold or given to relatives.

In addition to deeds, you may find yourself researching an ancestor’s land patent from the federal or state government. The Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office Records has millions of online records; start there to learn about public lands your family may have acquired. Learn more about locating land patents in our tutorial, available from <shopfamilytree.com/tutorial-map-your-ancestors-land-online-pdf>.

Mapping out the street

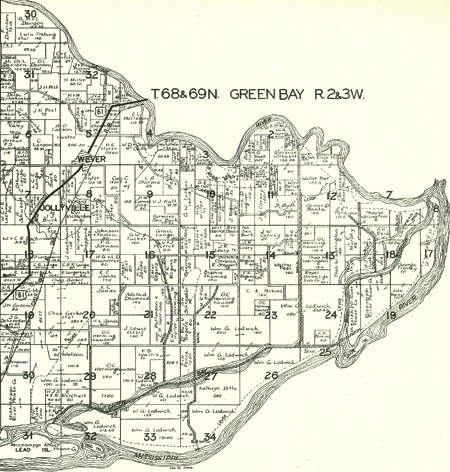

Next, I turned to maps to help me determine whether Caroline’s lot 10 was indeed No. 117 Grant Street. Neighborhood maps made before, during and after an ancestor’s era are valuable for the unique (and occasionally conflicting) details you can compare and compile. Some maps show just roads, rivers, mills, churches and the occasional homestead; others have landowners’ names. Look for maps, atlases and regional histories (which might contain maps) in free online collections such as David Rumsey Historical Maps, Library of Congress, Internet Archive, Google Books or HathiTrust Digital Library. Search for the name of the neighborhood, town or city, township, county and state. Also look for maps at major libraries near the place of interest.

For the O’Hotnicky home, I needed maps that reference lot numbers—most likely to be the maps created and filed by the original developers in town or county offices. Local governments also may have created master maps showing property boundaries, dimensions, changes to property lines, lot numbers and more.

At the Olyphant borough (town) hall, I found blueprint-sized maps of the neighborhood from 1973. In addition to the aforementioned details, the maps also labeled some businesses and churches. Lot 10 is on the west side of Grant Street, backing up to Holy Ghost Catholic church. The lot’s original dimensions and neighboring lots fit the deed description. The church eventually annexed the rear of Lot 10 and the next lot over.

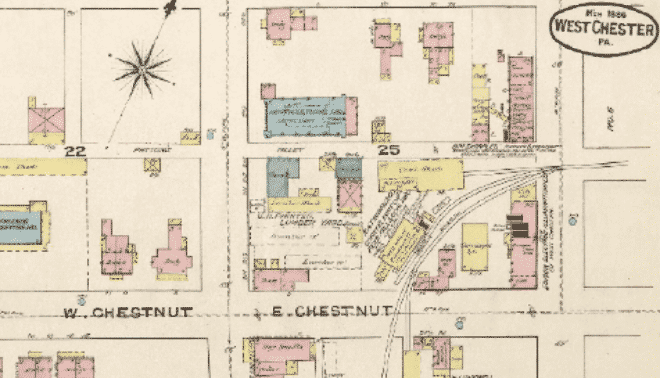

The next maps I turned to were Sanborn insurance maps. Published from the late 1800s and well into the 1900s, these detailed renderings of cities include building footprints and construction details, street names and house numbers, businesses, organizations and more.

The Library of Congress has a large collection of Sanborn maps <loc.gov/rr/geogmap/sanborn>, some of which are digitized. The catalog mentions Olyphant maps for 1893, 1898, 1903 and 1912, but they’re not online. A Google search for Sanborn maps Olyphant PA brings up digitized versions of all four maps at the Penn State University Libraries Digital Collections.

The 1893 map, drawn a year after the O’Hotnickys purchased their lot, shows the neighborhood was well developed, with homes and businesses lining the streets. Number 117 is shown on Jones Street, but on the east side of the street. That lot’s building footprint says “Foundation to be S.” According to a list of Sanborn map abbreviations <www.newberry.org/sites/default/files/researchguide-attachments/sanbornabbrv.pdf>, S means “store.” The smaller building on the west side of the street, where the lot number puts the O’Hotnicky’s, has a D for “dwelling.” The Holy Ghost Church is labeled “Hungarian church.”

Subsequent Sanborn maps, studied chronologically, show the neighborhood’s growth. In 1898, the large building at 117 (still identified as a store) seems to be completed. A large general store occupies a spot where, a few years later, the 1903 map shows a vacant space labeled “ruins of fire.” By 1912, that space has a town hall and fire station. The 1912 map shows the street name now called Grant and a parochial school across from the church (perhaps where the school-teaching nuns worked during the 1930 census). That map also adds the word tenements (a term for the crowded apartment housing often associated with immigrant quarters) to the Hungarian Hotel.

Modern Google Maps show how the Grant Street neighborhood appears today. Many of the buildings are the same. A search here for house number 117 points to Lot 10, on the west side of the street. You can’t count on Google Maps as a reliable source for house numbers in years past due to changes in numbering systems, but it’s worth noting that Google Maps adds to the evidence placing the O’Hotnicky’s house on the west side of the street.

Whichever side they lived on, all those maps depict old Grant Street as a vibrant Eastern European enclave. Residents packed themselves into rear dwellings (which the census noted with an R under dwelling numbers) and in tenements. The maps identify a meat market, dance hall, “liquors,” hardware and tin shop, general store, notions store and even an opera house, all within walking distance of the O’Hotnickys. Some of these places I would soon connect to the family.

Localizing the search

Now I was starting to know the neighborhood, and as more clues emerged, I could see where they fit. Relatives told me the O’Hotnickys “always went to Holy Ghost parish.” Of course! A parish history says Slovakian families—perhaps including Andrew’s parents—built the church in 1896. The parish office sent me baptismal, marriage and burial records for Andrew and his parents. Their graves were on a hill just outside town, where I also discovered other family burial places.

The same local relatives gave me a photograph of Andrew driving the Olyphant Hose Company No. 2 fire truck. A visit confirmed that was the fire station on the corner just past Holy Ghost church, a block from Andrew’s house. The station walls are covered in old photos (including a copy of Andrew on the truck) and a memorial plaque has Andrew’s name. From a retired firefighter who lives on Grant Street, I learned that Andrew’s brother, son and maternal relatives volunteered there. It was a Slovakian fire company and, apparently, a family tradition. I even found a 1937 newsreel on YouTube of Andrew driving the station’s fire engine (see how I found it at <lisalouisecooke.com/2015/02/amazing-find-ever-family-history-youtube-no-kidding>).

One of my most interesting finds was a 1926 photo of Grant Street buildings from the Genealogical Research Society of Northeastern Pennsylvania. When I showed it to the retired firefighter, he pointed to a tall building in the center. “A Slovakian immigrant named Bosak owned the bank,” he said. “He made a fortune bringing workers over from the Old Country and connecting them with jobs.” He added that the alley to the left was the entrance to Bosak’s court, “his tenement housing for the newest arrivals.”

Local histories confirm that Michael Bosak was indeed a wealthy bank owner (no mention of immigrant worker schemes). But I did notice that Google Maps still refers to that little side street as Bosak Court.

More sources added bits and pieces to my mental picture of Grant Street. An undated postcard of Jones Street appears to face toward the tree-fronted lot that I believe was 117, on the west side of the street. A single city directory for Olyphant (surprisingly sparse for that time period) support census evidence that Andrew spent time in the mines, and gives an address for another O’Hotnicky relative, possibly the fire-fighting brother.

I didn’t begin my research on the O’Hotnickys intending to reconstruct their neighborhood. But I did want to discover more about their family, and that’s where my questions led me. Rebuilding their surroundings is the closest I’ll ever get to strolling up the sidewalk to 117 Grant Street and introducing myself.

As it turns out, my neighborhood reconstruction project didn’t get shelved with the end of my O’Hotnicky research. Next, I wanted to identify Rose’s family. Her marriage license application gave me her maiden name. When I found her parents in the census, guess where they lived? At 118 Grant Street, directly across the street from Andrew and Rose.

Pin this article for later: