Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

For online genealogists, it’s the stuff of legend: a single Web site brimming with millions of searchable, digitized genealogical records — all available to you for free. You’ve been cautioned not to expect it, warned that such a treasure would certainly come with a price tag, as do digital document hot spots Ancestry.com <ancestry.com> and Genealogy.com <genealogy.com>.

Well, we hope you’re sitting down — because that Holy Grail does exist. It’s called HeritageQuest Online, and it puts some of family historians’ favorite resources just a few clicks away. Namely, the site serves up all US censuses from 1790 to 1930, Revolutionary War pension and land records, 20,000-plus published family and local history books, and an index to more than 1.6 million articles in at least 6,500 genealogical journals, as well as a recently added collection of Freedman’s Bank depositor registers from 1865 to 1874.

So what’s the reason for this Web site’s relative obscurity? For one, you can’t simply surf over to <www.heritagequestonline.com> and start searching; it’s not a free site in the sense of RootsWeb <rootsweb.com> or FamilySearch <www.familysearch.org>. Instead, parent company ProQuest runs HeritageQuest as an “institutional” subscription site, so you can access it only through a library or society that pays for it.

But that also means you, the average genealogical consumer, won’t take a hit to your pocketbook: If you belong to a library that subscribes — and with 2,600 nationwide currently enrolled, it’s likely you do — you can tap into HeritageQuest’s trove of records without paying a dime. Additionally, some family history organizations, such as the New England Historic Genealogical Society <www.newenglandancestors.org> and Ohio Genealogical Society <www.ogs.org>, provide HeritageQuest as a member benefit (your joining fee includes surfing privileges). Best of all, many subscribing institutions offer remote access, so you can search the site from your very own computer.

Whether you’ve just discovered HeritageQuest or you’re already in on the secret, come along as we venture inside each of its collections. We’ll teach you tips and tricks to make the most of its records riches.

Starting your crusade

The first secret: learning how to log on. Begin by going to the Web site of a subscribing library or society. Then look for a page listing research databases. For instance, my local public library’s home page has a link to Online Resources, including HeritageQuest. To use HeritageQuest at home, I select the remote access option and enter my barcode. That’s my library card number, which I keep handy in a document on my computer so I can just copy and paste it. The New England Historic Genealogical Society’s site logs you in automatically, so you don’t need to enter a user name when you follow the link to HeritageQuest.

If your connection goes “idle,” HeritageQuest will log you off. But you don’t have to start over at the subscribing institution’s site when you’re prompted to log in again — just re-enter your barcode or member number. (Note that the HeritageQuest site we’re describing here isn’t to be confused with the outdated — but still functional — one at <www.heritagequest.com>. The latter site represents the same brand, but exists to sell CDs and microfilms directly to consumers, not host genealogy databases.)

HeritageQuest’s main menu provides links to the site’s five collections: Census, Books, PERSI (short for Periodical Source Index), Revolutionary War and Freedman’s Bank. At the top of every screen, you’ll see four links. Click on Results List to return to your most recent search. Search History lists all the searches in your current session and lets you review, repeat or edit them. Help opens a window with tips for the collection you’re searching. Notebook holds notes that you add to a citation for e-mailing, printing or downloading (this feature doesn’t always work).

Each collection has a customized search screen and handles search terms differently. So you’ll need to tailor your surfing to a specific section’s quirks — which we’ll now explore collection by collection.

Unsealing the census

What’s a surefire way to excite genealogists? Put together the words census and online. After all, the federal government’s once-every-10-years head counts are family historians’ most beloved (and reliable) resource. Add the ease and immediacy of online searching, and genealogists go gaga.

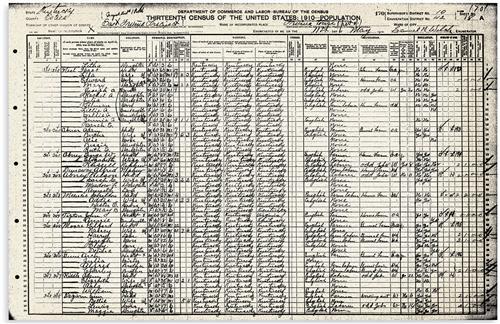

This potent combination has revolutionized family tree research. Rather than cranking microfilm, you now can view digital images of every US census page from 1790 to 1930 on your computer screen (except 1890, of which only fragments survive). The downside, of course, is you’ve typically had to pay for the privilege: Ancestry.com and Genealogy.com served as the primary census-image brokers.

Until recently, many genealogists didn’t realize HeritageQuest has the entire federal census, too. In fact, it offers the same images you have to pay for at Genealogy.com (except for the 1900 enumeration — see box, page 59).

In addition to the images, HeritageQuest has complete head-of-household indexes to 10 of the 15 publicly available censuses: 1790 to 1820, 1860, 1870 and 1890 (fragments) to 1920. (You can search the 1880 census for free on FamilySearch.) HeritageQuest’s 1930 index covers only Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Texas and Virginia.

Don’t look for more census indexes on HeritageQuest anytime soon: ProQuest has scaled back its plans to index all census years since reaching an agreement with MyFamily.com for joint distribution of HeritageQuest Online and Ancestry Library Edition. But many HeritageQuest subscribers also purchase Ancestry Library Edition, which includes every-name census indexes for almost all years (you can’t get remote access, however).

Since HeritageQuest lacks those all-encompassing indexes, you’ll have to be strategic about your surfing. The Search Census screen has tabs for Basic Search, Advanced Search and Find by Page Number. Unless you know the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) <archives.gov> microfilm number, Find by Page Number won’t help you. Instead, focus on the Basic and Advanced options — and adhere to these hints:

? Know your limits. Both searches let you search by first and last name. With the Basic form, you can comb all indexed censuses and states simultaneously, or limit your search to a specific year and state. The Advanced Search screen lets you narrow by town and county, age range, gender, race and birthplace.

? Go beyond basics. HeritageQuest’s Basic Search works best if you’re searching for an uncommon name. Otherwise, use the Advanced Search.

? Pile on parameters. If you get too many hits with the Advanced Search, focus your query by adding more criteria, such as an age range or birthplace.

? Look for different last names. Head-of-household indexes don’t always cover just one person per residence. Anyone with a different last name — such as a servant Or live-in mother-in-law — may be indexed.

? Skip the surname. The census search doesn’t require you to enter both first and last names. If you don’t know a woman’s married name, fill in as much as you do know on the Advanced form and leave the Surname box blank.

Remember, you’ll get no results from censuses HeritageQuest hasn’t indexed. To access those records, follow the Browse link below the navigation bar’s Census tab. The site will walk you through selecting a single year, state and county.

Hint: Before you make yourself bleary-eyed from browsing, use other indexes to pinpoint the appropriate page. For example, you can search the fully transcribed 1880 enumeration at FamilySearch — find your family there, and you’ll know exactly which page to call up once you’re on HeritageQuest. Look for other indexes and transcriptions at Cyndi’s List <cyndislist.com/census.htm>, Census Finder <www.censusfinder.com>, Census Online <www.census-online.com> and Census Links <censusIinks.com>.

Can’t find free indexes online? Check your library for print and CD indexes (or Ancestry Library Edition). You’ll find microfiche head-of-household indexes at many Family History Centers (branches of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library; visit the Family Search Web site to find one near you).

Preserving your finds

It’s easy to make copies of the census records, book pages and other documents you find at HeritageQuest online. Just display the record you want on your screen and click the Print button. A new window will appear with a printer-friendly version of the document. Then click on your Web browser’s Print button. When you display a census image, there’s also a link with instructions for using Adobe Reader to print larger census images.

You can save the electronic files to your computer, too, by clicking the Download button. The files come in one (or both) of two formats: detailed, high-memory TIFFs and smaller, less-space-hogging PDFs. Complete pension files are available only as PDFs, but you can download individual pages in TIFF format. With census and Freedman’s Bank images, you can choose TIFF or PDF format. Warning: Your TIFF downloads may fail if Apple QuickTime iS already installed on your computer. So if you have problems downloading a census image as a TIFF, get the Free Alterna TIFF <www.alternatiff.com> viewer.

To save pages from a book, click on the Download button and select a section or a range of page numbers. When entering a range, be sure to enter the appropriate page numbers — they don’t necessarily correspond to those used in the book: Page 5 iS usually 5, but page 5 in section 1 is specified as 1_5. So to download pages 5 through 10 in section 2, you’d enter 2_5-2_10. When you hit the Download button, Internet Explorer may block the download. Click on the warning bar near the top of your screen and select Download File to proceed. Then hit the Save button and select a folder on your computer to save in image as an Adobe Acrobat (PDF) file.

Paging Great-grandpa

With 7,922 family histories, 12,035 local histories and 258 primary sources, HeritageQuest’s book collection rivals the largest genealogy libraries in the country. But this online library has an advantage over its brick-and-mortar counterparts: You can search the collection’s entire contents in mere seconds, potentially finding your ancestors mentioned in a book you don’t have immediate access to or wouldn’t have thought to check.

The catch to this plethora of pages, of course, is you can’t expect to just type in your ancestor’s name — and presto! — there he is. You’ll likely get hundreds of hits on people unrelated to you, unless your ancestor has a rare name — in which case you might get no hits at all.

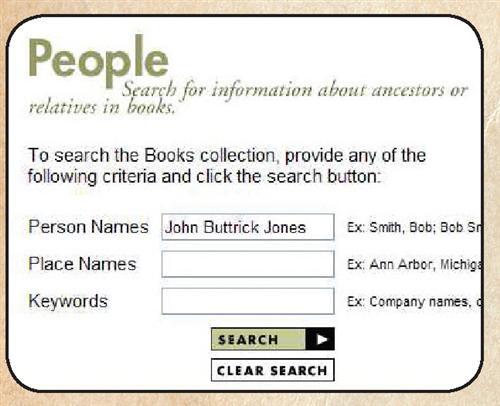

The site has a People search and a Places search, which offer the same three fields (Person Names, Place Names, Keywords) in different order. This is the trickiest HeritageQuest collection to search, so use these strategies for the best results:

? Add a place or keyword. A search on Robertson produces 4,608 matches, but add the town “South Worcester” (in quotation marks) to the place box, and you get a manageable 21 hits, including two that mention the Robertson family of South Worcester, NY. A caveat: This search will fetch any book containing both the name and place (or keyword) you enter, even if it’s The Robertsons of Pennsylvania referencing a neighbor from South Worcester.

? Get closer. HeritageQuest automatically uses “proximity searching” — looking for terms that appear close together — when you enter multiple words in one field: Your terms must be within five words of one another. So if you search for Dora Robertson, your results will include hits with middle names (Dora Augusta Robertson) and initials (Dora A. Robertson).

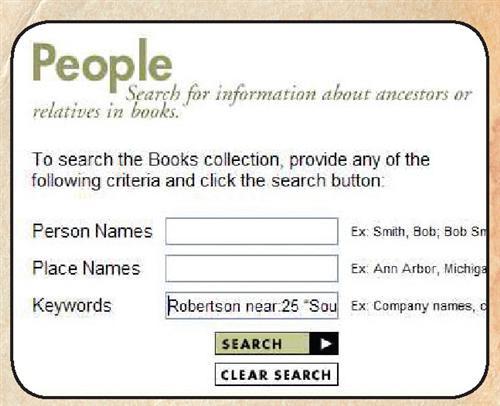

In addition, you can construct your own keyword proximity searches, even specifying how close your terms must appear. That’s a great way to narrow results: For example, say you want to find instances where the last name Robertson appears within 10 words of the place name South Worcester. Just enter Robertson near: 10 “South Worcester” in the Keywords box. This time, you’d get two matches instead of 21. No hits? Experiment with broadening your search terms’ proximity — specify, say, 20 or 25 words apart instead of 10.

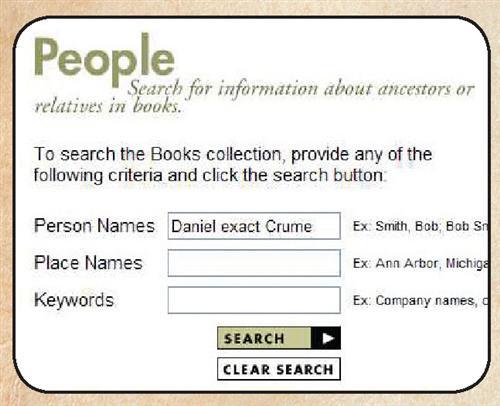

? Be precise. By default, matches include similar spellings: Search for Danzel Crume and you’ll find both Daniel Crume and Daniel Crum. To search on a particular spelling, precede it with exact, as in Danzel exact Crume.

? Go wild. You can substitute an asterisk for multiple letters, or a question mark for one. A search for we*er brings up hits on Weaver and Webster, and a search for wil?on gets matches for Wilson and Wilton.

? Turn a phrase. You can search for an exact phrase by surrounding it with quotation marks. Theoretically, that should be a good way to find a name, but it actually misses promising matches. Entering “Henry J. Hall” in either the Person or Keywords box produces one match. Omit the quotes from the Person box, and you’ll get 46 matches. They include J.Henry Hall and Hall, Henry J., as well as a few false matches, but also several occurrences of Henry J. Hall missed by the phrase search. Though it’s worth trying phrase searching to find names and places, use the name and keyword boxes and proximity searching for more comprehensive results.

? Bypass Boolean. Don’t bother with Boolean operators (and, or) to simultaneously catch several spelling variations — they dramatically slow down the search. Instead, repeat your search with each spelling variation.

? Test subjects. Want to limit a search to histories of the places where your family lived or to genealogies focusing on certain surnames? Here’s how: Click on Search Books, Publications and Search Publications, then hit the Browse button beside the Subject box. Type a last name or the name of a city, county, state or country in the Subject box and click on Jump. Then pick a single subject term, such as Pittsfield (Mass.) — History, and click OK to copy it into the Subject search box. Now type search keywords, such as “John French” or John near: 5 French, and click Search. This example turns up a reference to John French in a history of Pittsfield.

Once you find a book, you still have to zero in on the references to your family. Each title in your results list is followed by two links: View Hits and View Image. Select the former, then scroll down to the bottom of the resulting page. You’ll see a list that shows how many hits are in each section. Click a number, and you’ll go directly to the page containing the first hit. Then scan the image carefully — hits aren’t highlighted. To go to the next page with a match, click the right arrow by the Hit button. (You’ll need the free Adobe Reader <www.adobe.com/products/acrobat/readstep2.html> to view images.)

If our search strategies don’t get you results, don’t give up. You still can browse books for references to your kin. In fact, that’s a good idea anyway, as HeritageQuest sometimes misses valid matches. To browse all books on a specific place or surname, go to the main books page and click Search Books, then Publications, followed by Search Publications. Type the name of a town, county, state, country or surname in the Subject box, and hit the Search button.

Raiding the Revolution

Unless your US clan descends entirely from recent immigrants, you’re probably hoping — at least a little — to find a Revolutionary patriot in your pedigree. If so, you’ll want to fire up HeritageQuest’s Revolutionary War database.

The collection contains 81,000 pension files and bounty-land warrant application files. As a reward for their service, Revolutionary War veterans and their widows were eligible for pension payments and free public-domain (“bounty”) land.

HeritageQuest’s document images — scanned from NARA microfilm series M805 — name more than 138,000 veterans and their dependents. If the original file has fewer than 10 pages, the digital version includes them all. But if the original file exceeds 10 pages, documents not deemed genealogically significant are left out.

If you turn up one of those bigger files, it’s worth checking the microfilm for any omitted pages: For example, Heritage Quest’s 15-page file for Capt. James Knox of Massachusetts includes details of his Revolutionary War service, family Bible records and an affidavit by his widow Lydia. The 42 additional pages in the full file reveal Lydia’s date of death and include affidavits by their children and letters from descendants inquiring about the pension file. You can borrow films of the files’ complete contents — published on NARA microfilm series M804 — at your local library or Family History Center.

First, you’ll want to muster up your ancestor’s record using these search secrets:

? Think big. The Revolutionary War search screen offers four fields: Surname, Given Name, State and Service. But you likely won’t need them all. This database’s relatively small size — especially compared to the census and books collections — means most searches will produce a manageable number of hits. If you get too few matches, try broadening your search.

? Probe for payees. HeritageQuest’s index covers soldiers and their widows who applied for pensions, but not children and other dependents mentioned in the files. Both James Knox and his widow Lydia applied for pensions, so both of their names are indexed; however, their 11 children named in the pension file aren’t.

? Keep it simple. No need for complex search strings when you’re combing Revolutionary War records — you can’t use Boolean operators; nor can you include middle names or initials. And wildcard use is truly wild: A query for we*er brings up any name with the three-letter group wer, such as Brewer, Powers and Werth, but not Weaver or Webster. A question mark works strangely, too. Searching for crum? produces matches on Crump, Crumpton and even McCrum and Scruggs. Your best bet: Stick to basic name searches.

Pursuing periodicals

Ever wonder whether another researcher published findings about your family in a genealogical journal? PERSI is your No. 1 tool for finding out. It indexes 1.6 million-plus articles in more than 6,500 family history and local history journals. Created by the Allen County Public Library (ACPL) in Fort Wayne, Ind. — home to the country’s second largest genealogical collection — PERSI catalogs well-known titles, such as the National Genealogical Society Quarterly and the New England Historical and Genealogical Register, as well as obscure surname quarterlies and society newsletters. Coverage goes back decades for several publications.

The ACPL contracted ProQuest to develop the digital version at HeritageQuest, which debuted in 2004. (An older electronic version is available through the ACPI’s previous PERSI partner; Ancestry.com .) To use it advantageously, heed these hints:

? Pick the right parameters. PERSI indexes key names, places and topics — but not every name mentioned in the articles. You can search by surname, place name, how-to topic or periodical title. When searching on a common last name, using a place-name keyword will narrow the search to the most relevant matches.

? Be brief. Usually, searching on a state’s full name doesn’t work, so use the 2-letter postal abbreviation instead. A search for the surname Hershey produces 32 matches, but adding the keyword PA (for Pennsylvania) narrows the list to 20.

? Play your cards. As with books, wildcards are a great tool for searching PERSI — though there’s one key difference. In PERSI, asterisks work only at the end of your search term. So web* finds Webb and Webster; but you can’t search on we*er.

? Call the operators. You can combine several searches into one using the Boolean terms and and or. For instance, I’m researching Evan Jones, a missionary to the Cherokee Nation. It’s far more efficient for me to run a single PERSI search on the surname Jones and keywords Evan or mission* or Cherokee, than to do separate searches for Jones and each keyword.

Each PERSI citation includes a short article description and the periodical’s name and date. That’s enough information to find the article, but it would be better if each citation included the article’s exact title, author’s name and page numbers. Once you find a promising reference, you can request photocopies from the ACPL (up to six articles at a time for $7.50 plus 20 cents per page). You might be able to get the articles even more economically through interlibrary loan or on Family History Library microfilm.

ProQuest had planned to link PERSI citations to images of the articles they reference, but technical problems have curtailed that effort. Instead of indexing articles by their exact titles — which don’t always convey the content — the ACPL creates descriptive titles. That’s complicated the process of linking citation to image automatically. If ProQuest finds an economical way to do that, it’ll offer the article images through a separate subscription for libraries.

Decrypting deposits

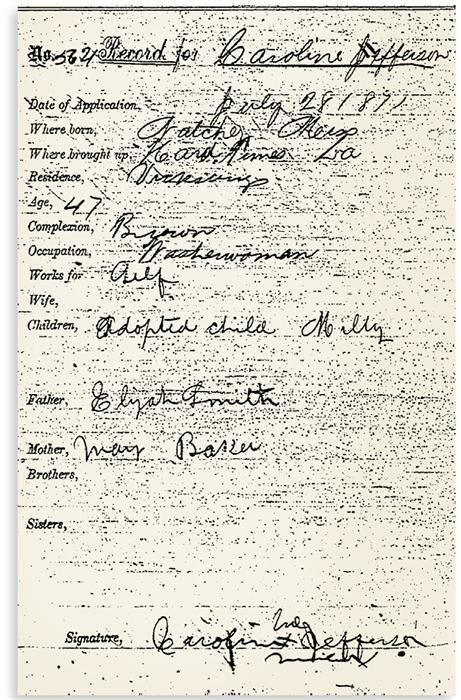

Tracing African-American ancestry before the Civil War is challenging, but Heritage Quest’s new Freedman’s Bank records can get you started. Created to help emancipated slaves, the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Co. had branches around the country. After it failed in 1874, depositors filed claims documenting their right to a share of the settlement. NARA microfilmed 55 volumes of records with depositors’ signatures and personal data — those films are the source of HeritageQuest’s database.

Besides transcribed family data, you’ll find digital images of the microfilmed registers, which often provide the depositor’s name, age, birthplace, complexion, occupation, signature and employer’s name. They usually name the depositor’s family members, and early books sometimes identify the former owner and plantation. (Family Search offers a $6.50 CD that presents much of the same data in pedigree-linked computer files, but lacks images.)

The best news for you: HeritageQuest’s index covers every name in the Freedman’s Bank records. Searching for the last name Crume, I found the 1873 application of Hager Henry, a 53-year-old housekeeper who named her mother Hannah Crume and brother John Crume. She was raised in Wilmington, NC, and describes her complexion as brown. Even though this record lacks a signature, it was exciting to see an image of the original document.

When you do your own Freedman’s Bank searches, use these tips to cash in on family details:

? Sound off. This collection supports Soundex searching, a method for nabbing similar-sounding surnames (see <www.familytreemagazine.com/soundex.html>). Just select Soundex from the Surname Spelling pull-down menu.

? Take your place. If you’re searching a common name, narrow your search by the bank’s location.

? Focus on first names. Don’t know your male relative’s last name or female kin’s maiden moniker? As with books, the surname field is optional—try searching on just a given name and bank location.

Once you’ve mastered these search tips, you can bank on something else: Your quest to dig up ancestor answers won’t be as harrowing as one of Indiana Jones’ adventures. But the discoveries will be every bit as thrilling.

Maximum Volumes

To zero in on the best matches in HeritageQuest’s collection of 20,000 family and local histories, model your queries after these four examples.

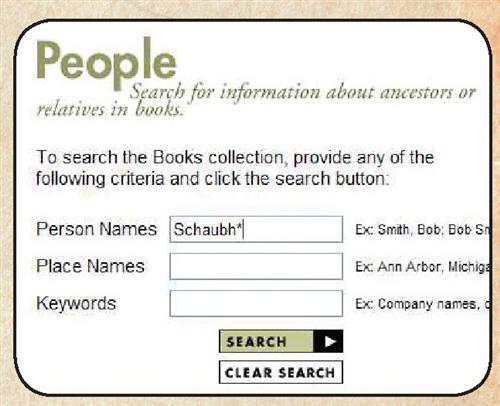

1. Search for an unusual name. You could enter just a last name (Schaubhut), a first and last name (James McMorris) or a full name (John Buttrick Jones). If at least part of the name’s unusual, you’ll get more manageable results — in the case of John Jones, one match with his middle name or 4,618 matches without it.

2. Narrow your search for a common name. To find the most relevant matches, run a search on a last name full name that appears close to particular town, county, state or country. For instance, typing Robertson near: 25 “South Worcester” will find the name Robertson within 25 words of South Worcester, a town in New York.

3. Find an exact spelling. You’ll need to precede a name with the word exact — as in Daniel exact Crume — if you want to weed out spelling variations (such as Crum or Crumes). If you don’t use exact when you search, list of matches will include similarly spelled names.

Just a few years ago, three rivals — Ancestry.com , Genealogy.com and HeritageQuest Online — announced plans to digitize all federal census records rom 1790 to 1930 and place the indexed images online. Which company would be the first to provide genealogists with easy access to our favorite records and dominate the online genealogy market? The stage was set: Scanning technology had matured, so microfilmed records could be digitized inexpensively. Several census years were already indexed, and many genealogists had Internet access. But it would still take a huge investment to index the remaining census years, link the indexes to the images and develop searchable databases.

The great census race ended with Ancestry.com in the lead, but closely linked to its former competitors. It provides online access to all US census records from 1790 to 1930 and has made every-name indexes for almost all of them. In 2003, Ancestry.com’s parent company, MyFamily.com, acquired Genealogy.com, and has left it to stagnate. HeritageQuest Online scaled back its online census efforts and partnered with MyFamily.com to market its services to libraries.

Product offerings from these three big online genealogy players are thoroughly enmeshed. Prior to the MyFamily.com merger, Genealogy.com licensed all its census records, except those for 1900 (which it already had scanned and indexed), from HeritageQuest Online. HeritageQuest’s book collection is available to consumers through Genealogy.com; it also forms the core of Ancestry.com’s book collection.

ADVERTISEMENT