Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

In this article:

Locating English Emigrants and Immigrants

Birth, Marriage and Death (BMD) Records

If you’re among the estimated 25 million Americans with English ancestry, there’s never been a better time to explore your roots. Along with such sites as Ancestry.com and FamilySearch, your British cousins have gone on an online genealogy records spree. In fact, you can do so much genealogy research from your home in the States that you don’t have to go on that dream trip to England to discover your roots there (but we won’t mention that to your other half). These resources and research tips will acquaint you with your English ancestors.

Locating English Emigrants and Immigrants

We think of English arrivals in America as dating to the Mayflower and Jamestown, and it’s true that England supplied a majority of the Colonial population. But even into the first half of the 19th century, English immigrants to the United States trailed only Germans and Irish. They actually outnumbered the Irish in the 1870 and 1880 censuses.

Look for English emigrants in the British subscription site FindMyPast.co.uk‘s 1890-to-1960 lists of passengers leaving the UK. Although departure records for folks from England are rare before 1890, other resources can reveal your early immigrant’s overseas origins. P. William Filby’s Passenger and Immigration Lists Index (Gale Research), found in many libraries and on subscription site Ancestry.com (but not in the version of Ancestry.com you use at the library), is a good place to start finding early US arrivals. The Family History Library (FHL) has “assisted emigrants registers” that give details on Englishmen who got a helping hand crossing the Atlantic (often as indentured servants). Clues also might lurk in non-immigration records, such as probate files; many Americans were mentioned in wills back in their home country. The English birth data at FamilySearch.org can suggest places of origin for people matching your ancestors’ names.

For English immigrants who arrived on US shores after 1820, use the passenger databases on Ancestry.com. You can search Ellis Island arrivals free at ellisisland.org and on FamilySearch.org. An index to passengers at Ellis Island’s precursor, Castle Garden, is free.

Mapping English Ancestors

Especially for earlier emigrants, make it your goal to narrow their locale in England to a particular parish, so you can consult the right church records. Landranger and other maps, available via www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk and www.streetmap.co.uk, can help you pinpoint English places; you can even search for house and farm names on these sites. The Institute of Heraldic and Genealogical Studies sells parish maps for every county in England as well as maps showing civil-registration districts. You can also consult the Phillimore Atlas & Index of Parish Registers by Cecil R. Humphery-Smith (History Press). The ever-helpful GENUKI site (for GENealogy researchers in the UK and Ireland) offers a searchable database of church locations.

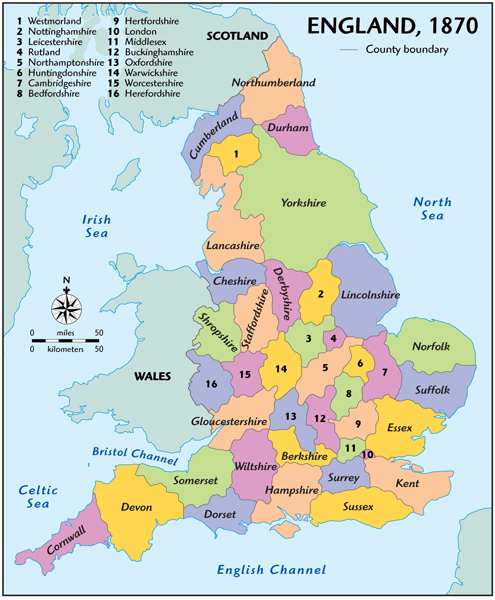

When mapping your English ancestors, keep in mind that England changed its county boundaries in 1974. Pre-1974 counties are often referred to using a system of three-letter abbreviations called Chapman Codes (“NFK” for Norfolk, for example). You can find maps of pre- and post-1974 county configurations in FamilySearch’s English research guide, and a guide to translating today’s counties into the historic ones used at GENUKI.

The Family History Library catalogs its English records according to the place names used in John M. Wilson’s work The Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales, published about 1871. When you search for records in the FHL catalog on FamilySearch, select Place-names and type the parish or town name into the search box. You’ll get suggestions for the county that town or parish is located in.

A wrinkle to remember in your research is that England switched from the Julian calendar to today’s Gregorian calendar in 1752, omitting 11 days after Sept. 2 to align with the solar year. So the day after Sept. 2, 1752, was Sept. 14. At the same time, the year changed from starting on March 25 to starting on the familiar Jan. 1. (Previously, the day after March 24, 1565, would have been March 25, 1566.) To convert Gregorian dates to Julian ones (and vice versa), you can use the calculator.

Census Records

If your ancestors left Mother England relatively recently, you may be able to trace the family using the English census, which began collecting genealogically useful data in 1841 and every 10 years thereafter. That first enumeration listed everyone in the household by name, sex, street, occupation and whether he or she was born in England. Ages are also given, but those for anyone over 15 were typically rounded down to the nearest multiple of 5. This census was organized by county, “hundred” (an administrative division of land) and parish.

Censuses from 1851 on list name, age (no more quirky rounding), occupation, relationship to the head of household, and parish and county of birth. Foreign births may list only the country. These censuses are organized by enumeration district. If you can’t find an ancestor in a given census, keep in mind that the English enumerations were a snapshot of the population on a given night–June 7, 1841, for example. So your ancestor may be listed at a workplace, boarding school or if traveling, a hotel.

You can search the 1841 through 1911 censuses for free at FamilySearch.org and link to record images at FindMyPast.co.uk (fees apply). Another free resource is the index on the volunteer site www.freecen.org.uk, where coverage varies by census year and county. FindMyPast.co.uk is the only site offering all the 1841 through 1911 census records. You can search by name or address, and all results are linked to digitized images. Ancestry.com has searchable censuses with record images from 1841 to 1901; the 1911 data are now being added.

Other online options include the Origins Network, with an index and images of the 1841, 1861 and 1871 enumerations. World Vital Records lets you search and view the 1841 to 1891 enumerations. You can search the 1901 census and the 1911 census (a National Archives website, powered by FindMyPast.co.uk). If you want to go the microfilm route, the FHL has microfilmed English censuses from 1841 through 1891, along with many different census indexes.

Supplement your census searches with directories of counties, towns and parishes (these are much like city directories in the United States). The FHL has a large collection; search on the county or city and look under the directories heading. The University of Leicester has created a digital library of Historical Directories, 1750 to 1919, with high-quality reproductions of many of these rare books.

Birth, Marriage and Death (BMD) Records

English birth, marriage and death (BMD) records began not long before the census, on July 1, 1837, making that 1837-to-1841 period a key demarcation in English genealogical research. Full compliance with the new civil registration requirements, which were voluntary until 1874, sometimes lagged, but 90 to 95 percent of all pre-1875 births and nearly all deaths and marriages got recorded.

Birth registrations generally include the child’s name, sex, birth date and birthplace, the parents’ names (including mother’s maiden name!) and father’s occupation. Death certificates usually give only the name, age, occupation, date, place and cause of death; a spouse’s name is sometimes listed or, if the deceased was a child, a parent’s name may be filled in the blank for occupation.

Marriage certificates typically contain the date and place; the church denomination if any, names and ages of bride and groom; whether each was single or widowed; their occupations and residences at the time of marriage; plus the names and occupations of each father. It’s often noted whether either father was deceased. When looking for marriage certificates, remember that weddings most often took place in the bride’s parish.

Researching in civil registrations is a two-step process. First, look for an ancestor’s event in the quarterly indexes produced by the UK Office for National Statistics. The earliest indexes list only name, registration district, and the volume and page number of the certificate. After 1865, death indexes include age at death. After June 1911, birth indexes also list the mother’s maiden name. And post-1911 marriage indexes give the spouse’s surname, handy for cross-referencing.

The FHL has microfilm copies of all these indexes through 1980, but doesn’t have any copies of actual certificates. The volunteer-transcription FreeBMD project has transcribed and made searchable some 200 million individual index records to date. If you can’t find your kin for free, FindMyPast.co.uk has fully indexed and searchable birth, marriage and death records. Another pay site, BMDIndex also lets you search birth, marriage and death indexes from 1837 on—covering a total of 255 million events.

Once you’ve found an ancestor in a BMD index, step two is to obtain a copy of the full birth, marriage or death certificate from the General Register Office. You can take advantage of an online ordering service and charge fees and overseas postage to your credit card. For standard service with the index reference supplied, orders are sent on the fourth working day after receipt, not including weekends or bank holidays.

Church Records

For early arrivals to the US—and to push your research back beyond 1837—you’ll need to turn to church records. (These continued after 1837 and can be a useful double-check for BMD records or way to fill in a gap.) The Church of England began keeping records in the 1530s, and beginning in 1598, parishes were required to make copies (“bishop’s transcripts”) for their local bishop. The originals and copies may differ slightly in details, so it’s worth checking both. Even if your ancestors were “nonconformists” (they didn’t belong to the Church of England) their marriages may have been recorded there. For other nonconformist records, see the pay site BMDRegisters.

Church records include christenings, marriages and burials. Marriages got separate registers beginning in 1754, and separate preprinted forms were introduced for all records in 1813. Most English church records are actually now kept in county record offices, which were considered safer, and they have been extensively microfilmed by the FHL.

Christenings, usually within a few weeks of birth, were recorded with at least the date and infant’s name; you may also learn the father’s name and occupation, mother’s first name, the infant’s birthdate and legitimacy, and the family’s place of residence. Beginning in 1813, the form asked for the date, child’s given name, both parents’ first names, family surname, residence, father’s occupation and minister’s signature. The birth date was sometimes included.

Marriage records can be more sparse, listing only the date and names of the bride and groom. Especially after 1754, you may also find each person’s status (single or widowed) and place of residence, plus the groom’s occupation. In addition to the marriage register, you may locate ancestors in a register of banns (announcements of intent to marry); check the FHL catalog by parish for these. Marriage licenses might have been issued in lieu of the three-week banns process; these are mostly kept in county offices and may be found in the FHL catalog under the name of the county (look under Church Records).

You can also consult several marriage indexes, the largest of which is Boyd’s Marriage Index, covering 4,375 parishes. It’s available from the FHL.

Prior to 1813, burial registers list the deceased’s name and burial date and may also give age, place of residence, cause of death and occupation. A wife’s entry may give her husband’s name, and a child’s record might list the father’s name. The forms introduced in 1813 call for name, age, place of residence, burial date and the minister’s signature.

You might also investigate cemetery records, as “monumental inscriptions” (MIs) on tombstones often give not only birth, marriage and death data but also cause of death, military service or occupation. Prior to the Burial Acts of 1852 and 1853, which led to the establishment of town cemeteries, most people were buried in church graveyards. Many MIs have been transcribed by volunteers; click on your ancestor’s county to explore these lists.

Online, the best way to dive into English church records is via FamilySearch.org’s International Genealogical Index of transcribed records, which in the updated version of the site are in databases such as England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975. FamilySearch.org also includes some digitized parish records. The ever-growing FreeREG project is transcribing parish records and posting. You can also click to online church records and other marriage records at Ancestry.com, British Origins, World Vital Records and FindMyPast.co.uk.

Probate Records

Probate records are another valuable resource for delving further back into the past, especially if your English ancestors were relatively well-off. Only about 10 percent of English estates prior to 1858 went through probate in court, but it’s estimated that a quarter of the population either left a will or was mentioned in one. It’s worth looking for probate records for your English ancestors.

The Church of England, which was in charge of probating estates until Jan. 11, 1858, had more than 300 special probate courts. To find the right court, consult the FHL’s 40-volume series of color-coded maps and probate keys. First you’ll need to use the book or paper maps (available at many FamilySearch Centers) to find the court. Then use the key (available along with the maps, as well as on microfilm and microfiche) to find the FHL call numbers for available records.

If an ancestor died between 1796 and 1858, you may be able to take a shortcut through indexes of estate-duty registers, which don’t require exact knowledge of the deceased’s residence. The actual registers, which recorded payment of a tax on all estates valued over 10 pounds, may also contain details not found in the original will. They are especially useful for estates in Cornwall, Devon and Somerset, where local probate records have been destroyed.

For later probate records, you can consult FHL microfilm of nationwide indexes to all wills and administrations of the Principal Probate Registry, which was created in 1858. Look in the catalog under England—Probate Records.

You can also search will records online in several collections at British Origins, which recently added the British Record Society Probate Collection of records from more than 20 counties dating as far back as 1320. FindMyPast.co.uk has a database of probate and wills from 1462 to 1858, and an index to death duty registers from 1796 to 1903. And the British National Archives’ Documents Online includes wills dating from 1384 to 1858 from the Prerogative Court of Canterbury and country court death registers between 1796 and 1811. Searching is free, with a small fee to download an image.

Military Service Records

Your English ancestor’s military service opens another avenue of possible inquiry. Army records begin in 1660; prior to 1847, most English soldiers made a lifelong career of military service. Records before 1872 are organized by regiment, so it’s useful to consult the regimental histories at the FHL (run a place search of the online catalog for Great Britain and look under the military history heading).

English naval casualties are also included in the graves database. Other naval records date as far back as 1617; many are available only through the National Archives (see Toolkit). You may find your English sailor ancestor in both the navy and the merchant marines: Seamen often moved back and forth and until 1853, enlistment was informal, typically lasting just three years.

Online, FindMyPast.co.uk offers an extensive collection of military databases. If your ancestor was an English “army brat,” don’t miss the databases of armed forces births between 1761 and 2005, and marriages between 1796 and 2005.

If an ancestor died while serving in one of the world wars, look in the Debt of Honour Register of the Commonwealth Graves Commission. It lists 1.7 million members of British Commonwealth forces. (Note that it also includes 67,000 civilians who died as a result of enemy action in World War II.)

For more assistance in your search for English ancestors, see the suggestions and research guides in the free GENUKI site. You also can search the British National Archives’ Access to Archives, which, while it won’t actually serve up old ancestral paperwork, can tell you where to look for it among more than 10 million records in 400-plus repositories across the UK. If all else fails, well, there’s always that trip to jolly old England you’ve dreamed about.

English History Timeline

- 1066: Norman Conquest of England

- 1534: Henry VIII forms the Church of England

- 1536: Henry VIII unites England and Wales

- 1558: Elizabeth I ascends to the throne

- 1588: England defeats the Spanish Armada

- 1607: England’s first American colony established at Jamestown

- 1616: William Shakespeare dies

- 1620: English Puritans land in Massachusetts on the Mayflower

- 1642: English Civil war begins

- 1660: Monarchy restored under Charles II

- 1688: Glorious Revolution replaces James II with William and Mary

- 1707: England, Wales and Scotland form United Kingdom

- 1783: Treaty of Paris ends American Revolution

- 1818: Regular Liverpool-to-New York City passenger service begins

- 1836: Charles Dickens writes The Pickwick Papers, his first novel

- 1859: Charles Darwin publishes On the Origin of Species

- 1887: Sherlock Holmes first appears in publication

- 1914: The Great War (World War I) begins

- 1928: Oxford English Dictionary completed

- 1936: Edward VIII abdicates the throne

- 1952: Elizabeth II ascends to the throne

- 1964: “British Invasion” begins with the Beatles’ appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show”

- 2011: Prince William marries Catherine Middleton

English Genealogy Resources

Websites

- 1901 Census Online

- Access to Archives

- BMDIndex

- BMDRegisters

- Commonwealth Graves Commission

- DocumentsOnline

- England GenWeb Project

- FindMyPast.co.uk

- FreeBMD

- FreeCEN UK Census Project

- FreeREG Parish Registers

- Gazetteer of British Place Names

- GENUKI

- National Archives 1911 Census

- Ordnance Survey

- Origins Network

- Streetmap

- Your Archives Wiki

Books

- Ancestral Trails: the Complete Guide to British Genealogy and Family History by Mark D. Herber (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Genealogical Research in England and Wales by David E. Gardner and Frank Smith (3 vols., Bookcraft Publishers)

- A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your English Ancestors by Paul Milner and Linda Jonas (Betterway Books)

- Phillimore Atlas & Index of Parish Registers by Cecil R. Humphery-Smith (History Press)

- Tracing Your English Ancestors by Colin D. Rogers (St. Martin’s Press)

Organizations and Archives

- British Isles Family History Society

USA2531 Sawtelle Blvd., PMB #309, Los Angeles, CA 90064 - The British Library (St. Pancras)

96 Euston Road, London, NW1 2DB, England, +44 843 208 1144 - Federation of Family History Societies

Box 8857, Lutterworth, LE17 9BJ, England, +44 1455 203133 - General Register Office

Box 2, Southport, PR8 2JD, England, +44 845 603 7788 - Institute of Heraldic and Genealogical Studies

79-82 Northgate, Canterbury, Kent, CT1 1BA, England, +44 1227 768664 - National ArchivesKew

Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU, England, +44 20 8876 3444

Tip: Calling archives in England? The United Kingdom runs on Greenwich Mean Time, which is five hours ahead of New York City and eight hours ahead of Los Angeles.

Tip: If possible, check both parish registers and bishop’s transcripts for your ancestors’ vital events. One set of records may contain more information, be more legible or cover more years.

A version of this article appeared in the November 2011 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT