Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

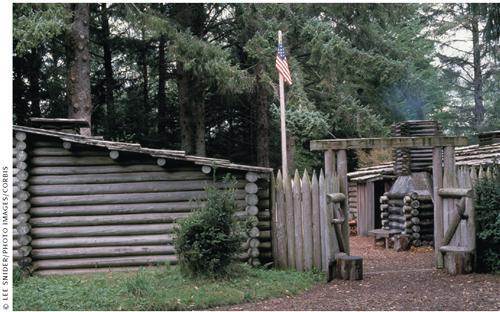

Two hundred years ago, when America’s most famous explorers, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, led their Corps of Discovery to what we now call Oregon, the land was sparsely inhabited by American Indians and a handful of European fur traders. Then the floodgates opened: Starting in the 1840s, at least 80,000 — and some say it’s more like 200,000 — hardy souls trekked the treacherous Oregon Trail looking for land, gold and opportunity in the Beaver State. Most ended up in its northwestern corner, where the Willamette (pronounced “Wuh-lam-et”) Valley’s fertile soil and mild climate nourished crops and cattle.

Settlers’ 1843 meetings to deal with wolves resulted in their first provisional government, and they received official-territory status five years later. In 1859, when Congress made Oregon the 33rd US state, fewer than 1,500 of its 53,000 white residents lived in the arid region east of the Cascade Mountains.

Americans still beat a path to Oregon, but it remains mostly rural, with Portland and Eugene/Springfield as its largest metropolises. Before you embark on your research, arm yourself with Connie Lenzen’s Oregon Guide to Genealogical Sources (Genealogical Forum of Oregon, $25). Then visit the state archives’ Web site <https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/Pages/default.aspx> to look up your ancestral county in the Historical County Records Guide and explore the Oregon Historical Records Index. This database lists records such as land claims, vital records and various county probates and censuses.

Lay of the land

In 1843, Oregon’s provisional government began giving free land to married couples. Then, under the Donation Land Act of 1850, citizens received real estate if they’d live on and farm it for four years. The Homestead Act of 1862 added a $34 fee and an option to purchase the property after six months’ residence.

Land claims may provide birth, marriage, citizenship and migration details. Microfilmed donation land claims are at the National Archives and Records Administration’s (NARA) Pacific Region facility <www.archives.gov/facilities/wa/seattle.html> in Seattle and at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> in Salt Lake City (check the catalog for Oregon and Washington Donation Land Files,1851-1903). Request FHL film at a branch Family History Center (FHC). You’ll find provisional land claims at the FHL and on the state archives’ Web site.

The General Land Office distributed the remaining land — you can search its patents database at <www.glorecords.blm.gov>. Records for subsequent land sales should be at the county courthouse — most aren’t on microfilm at the FHL.

Pioneering spirit

Your 19th-century Oregon ancestors may be on record in a pioneer file. Organizations such as the Oregon Genealogical Society, Oregon Historical Society (OHS) and Genealogical Forum of Oregon keep registers of pre-1900 settlers and their descendants. Also check for wagon train lists, diaries and biographies — you’ll find links to online resources at Oregon’s USGenWeb site <www.rootsweb.com/~orgenweb>. For $10, the Oregon-California Trails Association’s Names on the Plains Project can search its database of 12,600 surnames gleaned from Oregon Trail documents; visit <www.octa-trails.org/coed/namesontheplains.asp> for details.

Vitally important

Oregon began recording births and deaths in 1903, marriages in 1906 and divorces in 1925. You’ll find marriage and death records, which are restricted for 50 years, on FHL microfilm and at the state archives.

Birth records have a 100-year access restriction. Before 1903, only the city of Portland required the recording of births and deaths — they’re indexed on the state archives’ Web site. But you still might luck out: The site also has an index to delayed certificates (those issued long after birth, based on evidence such as baptismal records) for births from 1842 to 1903.

Check your ancestors’ county courthouse and local society record abstracts for marriage and divorce records that predate state record-keeping. You also should search Brigham Young University Idaho’s Western States Marriage Record Index <abish.byui.edu/specialcollections/fhc/gbsearch.htm>: It lists 16,500 mostly late-1800s marriage records from 17 Oregon counties. If you’re in Portland, peruse OHS’ Biography Card File of birth, marriage and death information from early resources, including newspapers.

Count ’em up

Oregon held provisional censuses almost annually beginning in 1842; generally, they list just heads of household. The FHL has indexes to the surviving portions of these censuses, as do OHS and the state archives.

The federal government first enumerated Oregon (along with Washington) in 1850, when it was still a territory. You’ll find this and other federal censuses at NARA facilities, the FHL, large libraries and through subscription at Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com >.

State censuses in 1865, 1875 and 1885 list only the heads of household; in 1895 and 1905, they name all family members. You can find these censuses at the state archives; check <https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/Pages/records/aids-census_osa.aspx> for lists of enumerated counties.

To arms

Oregon’s legislature formed the state’s first organized militia in 1847 to defend against attacking Cayuse Indians. Visit the state archives for early service records from the Indian Wars with the Cayuse (1847 to 1850), Rogue River (1855 to 1856), Modoc (1872 to 1873), Bannock (1878) and Umatilla (1878) tribes.

Although Oregon banned free African Americans, it also banned slavery and joined the Union just in time for your ancestors to leave Civil War records. Look for them in the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System <www.itd.nps.gov/cwss/soldiers.htm> online index to soldier records. Or consult Soldiers Who Served in the Oregon Volunteers, Civil WarPeriod, Infantry and Cavalry. Soldiers, their widows or their children may have applied for pensions — you can search the General Index to Pensions on microfilm at NARA facilities, the FHL and in Ancestry.com’s US Records Collection. Use the information from your ancestor’s pension index card to order copies of his pension records — for information, select Veterans Service Records from the pull-down menu on the National Archives home page.

To find your ancestors’ records from the Spanish American War, Mexican War and World War I, consult the state archives’ military-records research guide <https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/Pages/records/aids-military.aspx>. And check the archives’ Oregon Historical Records Index: It includes statewide enlistment and service records (1848 to 1928), as well as Roseburg Soldier Home applications (1894 to 1933).

Native sons

Oregon is rich with American Indian history: More than 40 tribes lived there before the heyday of white settlement. Native American Genealogy <www.accessgenealogy.com/native> has excellent information about each tribe and the state’s five reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) first set up shop in Oregon in 1848 under the territorial governor; after 1873, BIA agents reported directly to bureau headquarters in the nation’s capital. OHS and the Oregon state archives keep some BIA records, but most are at the NARA headquarters in Washington, DC. The FHL also has vital records for several Oregon tribes.

Since 1880, Indian youth from all over the Pacific Northwest have attended the Chemawa boarding school, which was founded in Forest Grove, Ore., as the Training School for Indian Youth; it moved to Salem in 1885. The National Archives has microfilmed Chemawa records among its BIA holdings, and you can view registers of admitted students (1880 to 1928) and graduates (1885 to 1921) at Sources2Go.com <www.sources2go.com>.

Oregon Guide to Genealogical Sources author Lenzen warns that many of the state’s records are still in archives and courthouses — not on the Internet. That means tracing your intrepid pioneer ancestors could take some resourcefulness on your part, and eventually you may have to chart your own course to the Pacific Northwest. The ongoing Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery bicentennial commemoration makes now a particularly good time to do it. But beware: Oregon’s virtues may tempt you to make a life in your ancestors’ homeland.

From the February 2005 Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT