Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Concepts of self and family that we bring to our research, whether we are historians or genealogists, are shaped not just by biological facts but by law and custom, historical accident and personal choice.

Concepts of self and family that we bring to our research, whether we are historians or genealogists, are shaped not just by biological facts but by law and custom, historical accident and personal choice.

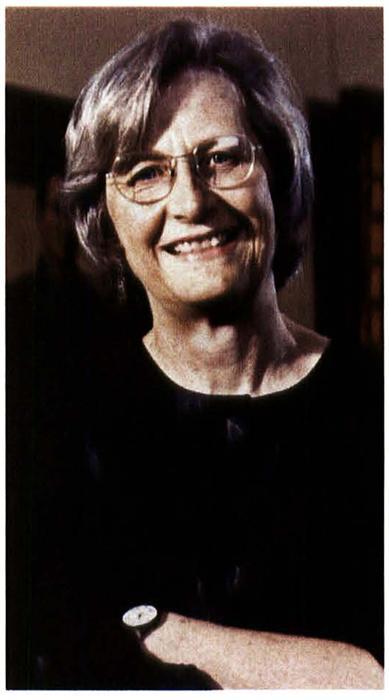

Perhaps I can illustrate this by talking about the name tag I was given at a New England Historic Genealogical Society conference in Boston several years ago. It read, “Ms. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Durham, New Hampshire.” I was not in the building 20 minutes when someone came and asked me whether Ulrich was a German or a Swiss name. I answered, “It’s my husband’s name. Actually I’m English. My maiden name was Thatcher.” I remember how proud I was of the name Thatcher when I went with my father as a young girl to the Hezekiah Thatcher family reunion. I remember standing up, as I had been instructed, and saying with confidence, “I’m Laurel, daughter of Kenneth who is the son of Nathan who was the son of Hezekiah.” I looked around the park and tried to see the Thatcher nose, or whatever other evidence of family connection was there. I was happy to bear my father’s name and pleased to be able to trace my lineage through him to Hezekiah.

But as I thought about that experience recently, the more artificial and strange it seemed. I am not just a daughter of Kenneth Thatcher, but a daughter of Alice Siddoway, who was the daughter of Alice Harries who was the daughter of Mary Rees who was the daughter of Eleanor Thomas, and there was no way on this earth that I would be able to say that at a family reunion — unless it was a reunion celebrating me. If I went to the Siddoway family reunion, I would be Laurel Thatcher, the daughter of Alice Siddoway, the daughter of Frank. If I went to the Harries family reunion, I would be Laurel, the granddaughter of Alice Harries, the daughter of Henry, and so on. At each point, I would have to connect back to a father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and so on, in a patrilineal succession.

Patrilineal families survive because women drop out in each generation. My father’s contribution to my DNA is no greater than my mother’s, but because law and custom says that I am a Thatcher, I will always be a Thatcher (except, of course, when I am an Ulrich). Law and custom also dictated that I would take my husband’s name when I married in 1958. I was happy to do that. There appears to be no escape. What genealogists call the “umbilical” line does not make a whole lot of sense on a name tag. Mine would have to say “Laurel Siddoway Clayton Jackson Ragg Harries Thomas Rees Anderson Ipson Folkman Wooley David Kitchen Thatcher.” And even I had to go look up those names because I could not remember them all.

Families are shaped not only by law and custom. They are also created by accidents of history. Why was a family reunion held in a park in Logan, Utah, dedicated to the memory of Hezekiah Thatcher? Because Hezekiah Thatcher and his wife Alena made choices that affected generations. By breaking with his own past, Hezekiah became the Adam from whence all things Thatcher flowed. He left West Virginia, went on to Indiana, then Illinois where he joined up with the Latter-day Saints and moved on to Utah. Because he and Alena were the first of a long succession of Latter-day Saints, they are remembered. The folks behind Hezekiah were as important, but family organizations, like family identity, spring not from biology, but from history.

From the June 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT