Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

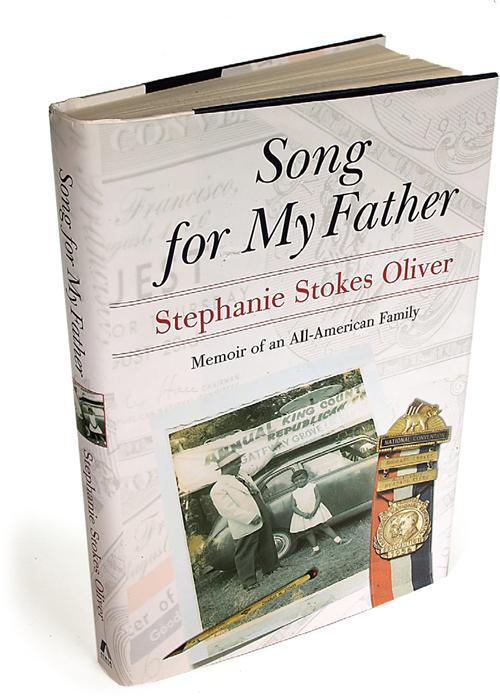

In the early 1960s, it was customary to be asked by whites, “When did you first realize that you were a Negro?” The question assumed that there was a defining moment – a traumatic event that rocked you into the realization that you were different from the mainstream. No, not just different – inferior.

Having always known I was African-American, and always liking what I knew, that was never an issue for me. Seattle was arguably more racially tolerant than most of the country. Though blacks composed less than 10 percent of the population, I grew up surrounded by a loving family and a community of solidarity about its black pride.

If the question had been “When did you realize that your black family was Republican?” – now that would have been another story. A defining moment did occur when I discovered that my parents’ political affiliation set us apart from the Negro mainstream.

It happened the year my father ran for lieutenant governor. He had the overwhelming support of our predominantly black Central District, so it hadn’t occurred to me that there could be any dividing line between him and his constituents, and he never spoke of one.

In 1960, even as a second-grader I knew that politics loomed large, not only in our family, our community and our state, but also in the country. As the presidential election drew near, my teacher got the bright idea to hold a mock election. Standing in front of our racially mixed, predominantly black class at Madrona Elementary, Mrs. Bracksburg, who was white, asked, “If you could vote, who would you vote for? Raise your hand if you would vote for Democrat John F. Kennedy.”

Many hands shot up quickly, I noticed.

“Now, raise your hand if you would vote for Republican Richard M. Nixon.” My hand went up just as proudly as the others had. But immediately, I felt a stillness in the air. Glancing around, I realized that mine was the only hand up. By the time recess came, I knew that meant trouble.

As time passed, I pieced together the family tradition. As a boy in his native Kansas at the turn of the century, Daddy had lived among colored folks who were largely Republicans, still loyal to the “party of Lincoln.” In the 1930s and ’40s when many African-Americans made the switch to the Democratic Party in support of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, Dad considered changing parties, too. But fresh out of law school and active as co-chair of the Young Republican Federation, he felt committed to his party. When he moved to Seattle, the GOP showed commitment to him by backing his candidacy in half a dozen elections. And on the national level, he was given prominent roles as a delegate or alternate or reading clerk at the presidential nominating conventions, which he never missed for more than 30 years.

Although my parents weren’t by any means the only black folks who were active Republicans in Seattle, being in a black Republican family was not the norm. We were minorities within the minority.

Emancipation had occurred 40 years before my father was born and almost a hundred years before I was in second grade. But because a Republican president named Abraham Lincoln had freed the slaves, my father felt free to vote Republican.

ADVERTISEMENT