Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Your ancestors were more than just names and dates. They were real people who experienced life in the contexts of their families and communities. To see them in these contexts, try creating personal, family and historical timelines. These tools can help you organize, plan and evaluate your research by showing at a glance what you’ve learned, what information is missing and where you could turn next. Read on to learn how you can create timelines for your family.

Personal timelines

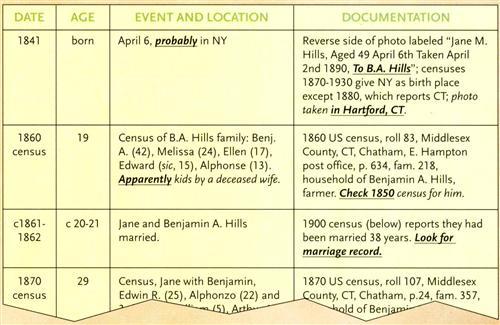

As you begin to focus your research on an individual, create a chronological profile of that person’s life that you can expand as you learn more. You’ll find a template for these timelines in The Unpuzzling Your Past Workbook (Betterway Books) and online at <www.familytreemagazine.com/freeforms> (scroll to the biographical outline and click on PDF or Text to download it). Before you find a lot of information on that person, you might want to create a timeline on your computer. A spreadsheet or a table in a word processing document provides unlimited space and can be updated easily. My preferred format has four columns:

Date: Write the date of each event in the ancestor’s life in chronological order.

Event and location: Include any information you uncover about the ancestor, such as birth and death, religious milestones, education, employment, military service, marriage(s) and land transactions. If you have questions about specific details, use qualifiers such as likely and probably to explain your uncertainty (for example, “born April 6, probably in New York”). An event description can be as brief as “bom somewhere in Alabama,” or it can be several sentences telling a family story. Recording the place is important because you’ll want to look for additional documents in each locality. Remember that an important genealogy strategy is to use the “known,” including places, to work toward the “unknown” family facts.

Documentation: Citing your sources is essential. Entries in this column can be full or abbreviated citations. For example, the full citation for Elizabeth Croom’s estimated birth date of 1808-1809 could read, “1850 US census, roll 230, Caddo Parish, Louisiana, p. 358, family 54, household of Isaac Croom (including Elizabeth, age 41).” An abbreviated citation could read, “1850 census, Caddo Parish, La., p. 358, fam. 54, showing Elizabeth, age 41.” If you do abbreviate the citation, be sure to include the full documentation elsewhere in your notes.

When you list every event you’ve identified in a person’s life, you see in one place what you’ve learned, which sources provided the information, which questions remain and where discrepancies need to be resolved. As you plan your research, the profile helps you concentrate on even the smallest details. (Remember that if you include information from undocumented family histories — paper, electronic or online — you must research them to determine their accuracy.)

Below, you’ll see a profile of Jane M. Hills after basic census research. As soon as I print out a timeline, I underline and italicize questions and ideas for future investigation. Consider creating such a timeline for both of your parents. What you don’t know about them might surprise you. After my mother died, I created a timeline of her life and was amazed to see probably, possibly and check sprinkled throughout the document, which immediately became a useful research checklist.

Personal Timeline: Jane M. Hills

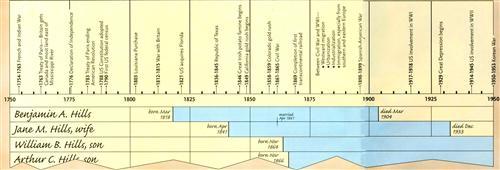

Family Timeline: Hill Lifespan Chart

Family timelines

Adding information about relatives will help you see the big picture and connect events. For example, a timeline revealing that a woman saw her three sons go to war helps explain the family story about her sitting in her rocking chair as an old woman, holding a picture of the youngest son as tears rolled down her cheeks. Putting the clues together will lead the thorough genealogist to look for military service records and evidence of the young soldier’s possible death in the war.

Besides being a valuable reference, a family timeline also will help you recognize and evaluate interactions between relatives and generations, birth order of children, and family migrations in relation to children’s birthplaces. You also can use these documented timelines as outlines for biographical sketches and family histories. You might not need to create a comprehensive family profile for all ancestors, but this tool is essential for those you study in depth or consider “brick walls.”

A multipage profile detailing my great-grandmother Maggie’s life saved me considerable research time. Although I knew where Maggie’s mother lived in 1910, my search for her 1910 Soundex entry had been unsuccessful. (Soundex is an index based on the sounds, or letters, in surnames. It’s often used to locate census records.)

Rather than scanning for her mother’s household in page after page of the county’s lengthy census, I consulted Maggie’s profile, which includes entries on her husband, children, parents and siblings. The timeline reminded me that in 1903, the widowed Maggie had returned to her hometown; I speculated that as a single mother with two young daughters, Maggie probably was living with her mother in 1910. Locating Maggie’s Soundex card took only a few minutes. That card led me to the census record listing all four females in the household. (I then added the record to Maggie’s profile.) I had not found her mother’s Soundex card because the indexer had misread the name on the census and thus created a far different Soundex code from the one I tried. Consulting the profile for ideas taught me a valuable lesson for future research planning.

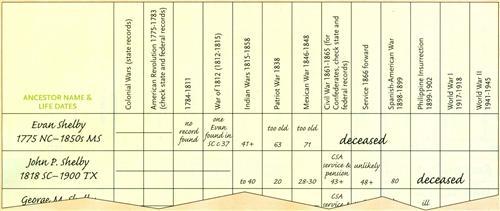

Another type of family timeline is a military-records checklist. You can insert the names and life dates of family members to determine who might have served in the military and which military records you could research.

Lifespan timelines, such as the one above, offer another perspective on ancestral families. When you chart relatives’ lifespans, you gain perspective on whose lives overlapped, whether certain ancestors were alive when their grandchildren were born, who experienced major events such as the Great Depression and so on.

You can create your own versions of these two charts on graph paper or as tables or spreadsheets on your computer. Personalize them by choosing the time periods your charts will cover and adding events relevant to your family.

Reference books and Web sites such as those listed at right will help you identify major historical events and periods. If you prefer pre-printed forms, a military-records checklist and two lifespan timelines are available in The Unpuzzling Your Past Workbook; the military checklist also is online at <www.familytreemagazine.com/forms/download.html>.

Historical timelines

Family history involves not only searching for proven generational links, but also striving to understand our ancestors’ roles in history and how certain events may have affected their lives. When you were a student, did you think about ancestors when you read about the Stamp Act, westward migration, industrialization, the Roaring ’20s or the New Deal? Your forebears lived through and felt the effects of such events. Whether they braved the hardships of the frontier or economic depressions, they were part of history.

Plugging historical events into an ancestor’s personal timeline helps you see his or her life in a broader context. When you compare general history with family history, you may discover that a gap in an ancestor’s life story was filled by a trek westward in search of gold. You may uncover a connection between the flu epidemic in 1918 and the deaths of family members that year.

Gathering historical information will broaden your knowledge of local, county, state, regional and national events that influenced your ancestors’ lives. Timelines in history textbooks and online usually pinpoint events deemed most important by the author. Don’t limit your perspective by looking only at these, but use them to jog your memory or for ideas for further reading.

While national and state histories often concentrate on political, military and economic events and leaders, county and local histories often focus on settlement in the area, the development of churches and schools, local leaders and ethnic groups, and the crops and businesses that shaped the local economy. Histories of farming practices, occupations, weather, cooking and other specialized topics can enhance your understanding of day-to-day existence in the time and place your ancestors lived. If your local library doesn’t have books on your topic of interest, ask about interlibrary loan and consult booksellers’ catalogs.

Genealogists benefit from investigating history from many angles. As a case in point, my chronological profile of Elliott Coleman shows that in 1872 he moved his family from Tennessee to south-central Texas, where he divided his time between farming and working as a carpenter until his death in 1892. The bare facts tell only part of the story. History helps explain one of Elliott’s surviving letters and perhaps one of the reasons for the family’s financial problems indicated in county records, letters and later interviews.

Historians of the Great Plains and of Texas explain that the Plains’ arid conditions reach deep into Texas and that many 19th-century farmers learned the hard way that the drier climate was not suited to traditional farming techniques or crops, especially those from the southeastern states. Such observations are not idle words when they concern ancestors. A prime example is the decade of drought that began in the Plains and parts of Texas in 1886. In October of that year, Elliott wrote a letter from central Texas (which he knew as west Texas) to relatives in Virginia about the hard times his family was experiencing. The drought had ruined the cotton crop, the corn crop was “also short” (limited) and “the oats was only tolerable.” He observed, “Western Texas is not a reliable farming country and I don’t think a plow should ever have been brought west of the Colorado [River].” Seemingly with frustration and/or disappointment, Elliott expressed his desire to return to his native Virginia, indicating that if he continued to starve his family there as he had in Texas, at least they’d starve among friends and relatives.

Whether your ancestors experienced traumatic events or led fairly ordinary lives, placing them into historical context will enhance your genealogical research. Each time you begin studying an ancestor in detail, create a chronological profile — either with a prepared form or a computer document. The more personal, family and historical events your timelines contain, the more likely you are to feel that you know your ancestors.

Links to the Past

WEB SITES

American and British research guides

<www.libraries.rutgers.edu/rul/rr_gateway/research_guides/history/history.shtml>: Click on Sites Organized by Subject for links to all sorts of resources.

American History Timeline

<www.si.edu/resource/faq/nmah/timeline.htm>

American Memory Collection Finder

<memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/finder.html>

An Outline of American History from the US Department of State

<usinfo.state.gov/products/pubs/history/toe.htm>

United States of America Chronology

<campus.northpark.edu/history/webchron/usa/usa.html>

US History Timeline

<www.infoplease.com/ipa/a0902416.html>

BOOKS

• The Almanac of American History by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. (Barnes & Noble Books)

• Encyclopedia of American History, 7th edition, edited by Jeffrey B. Morris and Richard B. Morris (HarperCollins)

• Timelines of African-American History: 500 Years of Black Achievement by Thomas Dale Cowan and Jack Maguire (Berkley)

• Timelines of American Women’s History by Sue Heinemann (Berkley)

ADVERTISEMENT