Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

If you’re like so many genealogy buffs, language barriers prevent you from learning everything you can about your family’s past. Unfortunately, most of us shy away from foreign-language resources.

Eso es demasiado malo, porque hay una mejor manera!

Qu’est tant pis, parce qu’il y a une mieux facon!

That’s too bad, because there’s a much better way!

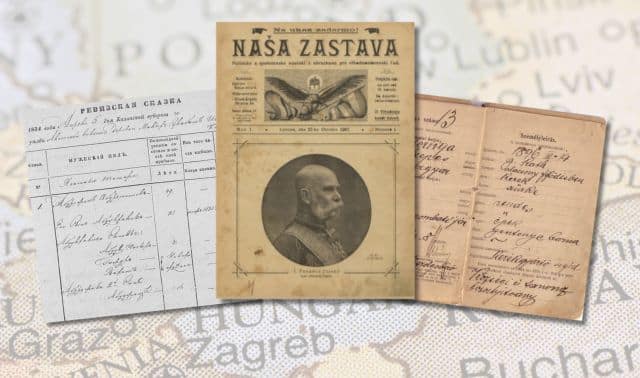

You can pry answers about your ancestors out of non-English genealogy materials quickly and easily — even if you can’t speak or read the language. Bring on those family treasures: the diplomas, immigration records and land deeds inscribed in the languages of your past. Open those coveted diaries and personal letters filled with details of your heritage. From marriage certificates to emigration records, baptism records to obituaries, these records of your ancestors’ lives are just waiting to speak.

With the help of key reference materials and the assistance of language professionals, you can finally find out what’s written in these family records. Plus, you’ll learn what’s written “between the lines” — sometimes priceless secrets about your legacy. Whether your goal is tackling the marriage records in the Italian Stato Civale, deciphering those old family recipes in Norwegian or conversing with Great Uncle Hans when you finally visit Denmark, language can help you discover your legacy.

Y usted aprenderá tanto más sobre su pasado!

And you’ll learn so much more about your past!

REDISCOVER FORGOTTEN LANGUAGES

In your ancestors’ native lands and later in the United States, language served as a unifying force — the tie that binds. Language meant connection; it forged alliances, smoothed over differences and spoke to a shared vision. Many years later, Romanian, German or Lebanese may seem totally foreign to your ears and eyes. But these were the words of your forefathers: the newspapers they read, their conversations over supper, the words they used to pray.

Yet now these languages are forgotten by their American descendants — why? In less tolerant days, a foreign language often carried a stigma for new arrivals. Sadly, it was more practical to be “modern”; many first-generation children barely learned their parental tongues. Knowing your clan’s tradition for preserving or discarding their native language (for example, Great-grandfather still wrote in Czech in 1924) can give you a rare glimpse into how your forebears lived.

Before you begin the process of unlocking foreign documents, understand that genealogical translation involves much more than just deciphering foreign words, or even mastering foreign alphabets, such as Hebrew or Cyrillic. Over the years, the meanings of words themselves have changed. Wirth means innkeeper in modern German, but years ago it meant landlord. Terms for professions, sicknesses and other important words have evolved or become archaic. Even the days of the week were written differently in some languages a century ago. Alphabets also transform over time, as Russian did after the 1917 revolution. Old German scripts are written in a dying language that hasn’t been taught since 1941.

Add to this that many immigrants had little chance to learn how to write — even in their native tongues. Great-great-uncle Anton may have mixed Hungarian and English in the same sentence. Or spelled new and unfamiliar words by ear. Or used no punctuation — where do his run-on phrases begin and end?

Like you, your ancestors occasionally misspelled — is that casa (house) or cosa (thing)? Splattering fountain pens and writing as illegible as our own can make deciphering your foreign-language legacy a puzzle. But what a joy when the words finally come forth.

Cosi otteniamo iniziato!

So let’s get started!

START BY DOING IT YOURSELF

Many texts will provide you with translations for basic genealogical terms, the kind you find in official records. So it’s simple to learn that in Italian, Sindaco is mayor, and Municipio is town hall. Klingenschmied means your German ancestor was a sword maker; Ullersmann means he was also father of the bride. A.G. (Amtsgericht) is district court. Old church records are almost always in Latin; for example, agricola is farmer, spurius means bastard. And the abbreviation D.S.P. is decessit sine prole — died without issue. FamilySearch <www.familysearch.org> offers a number of genealogical word lists and letter-writing guides for foreign languages. (Click on the Search tab, then Research Helps, then Sorted by Document Type. From here, you can view links to all word lists or letter-writing guides.)

This approach may suffice for isolated words. But don’t try to translate the whole diary of your 18th-century Oslo ancestor using a Norwegian-English dictionary. Even if you could find a sufficiently old one, the rules of grammar in Norwegian — or most any language — will surely defeat you. If you could understand him, Uncle Lars would tell you, “De må må vite språket!” (“You must know the language!”).

Computer-based translators have added a powerful new language resource to the genealogist’s toolkit (see the Toolkit in the February 2001 Family Tree Magazine for a guide to machine-translation aids). Just type in a sentence, and Spanish becomes English. Or French becomes Finnish. Does this mean that you can just “cyber-translate” all your foreign language family records? Probably not.

While electronic translators do a great job of interpreting short, direct sentences, language has many nuances that computers simply aren’t designed to convey. For example, they can’t recognize German compound words, marvelous strings that say an entire sentence in one word. They won’t translate the “gender” case of nouns, verbs and adjectives common in many foreign languages, causing you to wonder if a passage is about your great-great-uncle or your great-great-aunt. And computer-based translators can’t distinguish between many different meanings for the same word (I voted for Banknote Clinton — I mean Bill Clinton!) They are terrific tools, but won’t yield all the information that a careful genealogist needs.

SEEK PROFESSIONAL HELP

To really understand your ancestor’s words, you need the help of a special kind of professional: the genealogical translator. Part linguist, part researcher and part historian, these professionals translate not only across languages, but across centuries as well.

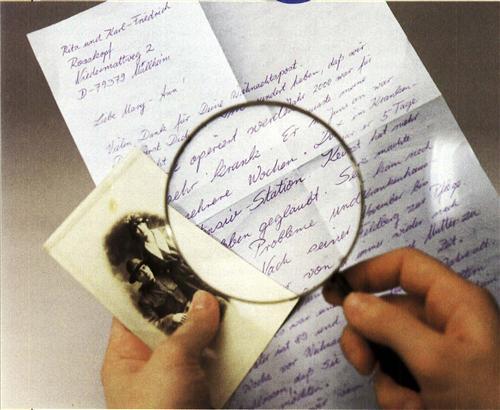

Good translators can decode more than just words. They can often tell you about the person who wrote them, when they wrote (even without a date), where they wrote (even without a postmark), their level of education (despite lack of diplomas) and maybe even their profession and religion. How can they do that?

Professional translators draw on unique backgrounds, training and resources to reveal the secrets of your family’s past. Elke Hedstrom, (e-mail elke.hedstrom@home.com; <www.geocities.com/elke4444>) is a genealogical German translator with a doctorate in 17th-century German literature and a master’s degree in library science. Her translation tools include a 32-volume dictionary that traces German words back to their 15th-century roots. Linguist Inna Oslon (e-mail inoslon@mindspring.com; <www.fastlane.net/~inoslon>) is an expert in the translation of Russian and Ukrainian. “To do this work properly,” Oslon says, “you must be a master in the history of the language. You must understand how words have evolved over time.”

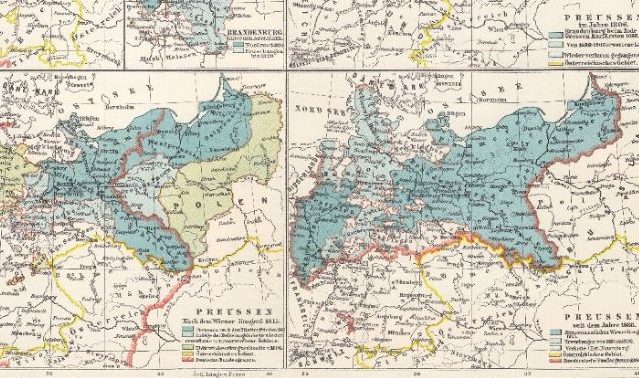

Genealogical translators are well-versed not only in the current geography of nations, but also the geography of the past. Polish translator Adela Chudziak-Kuchinka (e-mail szynon@hotmail.com; <akuchinka10.tripod.com/polishgentranslate>) has been serving the needs of genealogy clients for more than 20 years. She says, “I can draw on detailed maps, encyclopedias and gazetteers to identify even long-forgotten locations mentioned in your old family records.”

DECODE OLD WORDS

For the professional translator, every old word carries a kind of “linguistic DNA” that can reveal its past. For example, casa simply means “house” in modem Spanish. But coza indicates the writer probably originated from Andalucia. And cossa, if the spelling is accurate, may date the passage to the 17th century. Vosotros, an archaic verb conjugation, is a term of respect; perhaps a clue to family or social relationships.

“A professional can often date an old correspondence simply by the context of the letter,” Chudziak-Kuchinka explains. “We can spot the fads and trends of a historical period, or a style of writing from, say, the 18th or 19th centuries. A good translator can also recognize subtleties, like irony or humor, which can completely change the meaning of a sentence in an old letter. And to the trained ear,” she notes, “a dialect may belie a region or even a specific town.”

Immigrants often had to improvise ways to describe their new land. “They couldn’t always express themselves clearly,” says Oslon. “As a translator, I find a way to bridge that gap.” Good translators can decode almost untranslatable idioms (such as “It’s raining cats and dogs!”). They can recognize indigenous words for food names, festivals, local customs and rich folk traditions, which can reveal the “flavor” of your ancestors’ lives.

One client presented Inna Oslon with a unique challenge. “It was a fragile reel-to-reel tape recording of their grandfather telling old Ukrainian folk tales,” she recalls. “I had to listen to that scratchy amateur tape over and over, but I finally deciphered a priceless oral history.”

The vagaries of war, politics and commerce may have left languages in your past that have nothing to do with your nationality. For example, Western Ukraine was once part of Poland. “So old deeds and marriage certificates carry their instructions in Polish,” Olson says. “But the answers are handwritten in Ukrainian.” During the same period, some villagers actually wrote in Ukrainian, but spelled their words using the Polish alphabet. “Believe me,” she says, “only a professional linguist can unravel something like that!” For some emigres, Russian wasn’t their native tongue. They were Jewish immigrants, speaking and attempting to write a Yiddish version of Russian.

FlND THE RIGHT PERSON

What should you look for in a good translator? Most experts agree that truly effective translators virtually must be native speakers of the language. “There are many things that only native speakers know,” says Chudziak-Kuchinka. “Their understanding is broader. They know the people, as well as the traditions, culture and customs of the land.” Advanced education abroad is always a plus. The translator should be fully bilingual in English, sensitive to genealogical issues and familiar with the writing styles of the past.

In short, while your Czech-speaking third cousin or the high school French teacher may be well-meaning, she may not be entirely equipped to handle the nuances of old legacy documents. Nor are corporate translating services; they usually handle present-day translations for international firms.

One easy way to find the right translator for your family treasures is to contact genealogical, historical and ethnic research centers related to your mother tongue. Or inquire with the genealogical archives in a state where your target language was once widespread (such as Pennsylvania for German, Minnesota for Danish, New Orleans for French). Any good reference text can provide the contacts you need (see the box on page 65).

Once you’ve identified professionals in your target language, approach each with an introductory letter or e-mail. Provide the basics — indicate the document’s language, the subject matter (if you know) and the number of pages. Also indicate the type of document (diary, letters, etc.), its present condition and the approximate age, if known. Be as specific as possible. “To better acquaint the translator with the complexity of the task,” Chudziak-Kuchinka advises, “it is always a good idea to mail or fax a representative page of your material.”

As with any research work, submit only photocopies. Always retain your originals and take care when duplicating them. Color copies may preserve some of the contrast in old script. If the original is very crisp (as with a typed birth certificate), you might be able to scan it to a file and e-mail it. “Some translators can also work directly from microfilm. You should ask,” Hedstrom says.

But how quickly will you finally be able to read Great-great-uncle Gustave’s letters? “Naturally, work time varies greatly with the complexity of the document,” Chudziak-Kuchinka says. “Still, I can often turn-around simple documents in only a few days.”

Finally, agree on a finished product. Translators may be able to provide their materials by fax, e-mail, mail and as paper or diskette. (Specify an operating platform, such as PC or Mac; computers have languages, too!)

Now surely you’d believe that such a service — requiring so much scholarship and careful work — would be very expensive. But in fact, genealogical translation remains one of the best bargains in family history. Rates vary, but many documents can be translated for less than 15 cents per word — just $20 per typed page.

Very old documents and handwritten materials may cost somewhat more because the task is so labor-intensive. “If clients send me a representative page and number of pages, I can give them an estimate for the entire document,” Oslon says. Surely, having your ancestors’ foreign-language records translated can be one of the best investments you can make in your genealogy research.

DO YOUR PART

To boost your chances for fast, accurate translation, there are a few more tricks about submitting your materials. For instance, old church records are a frequent target for translating. Chronicling marriages, births and deaths in the parish over centuries, these are the gold mines of genealogy.

The bad news? “Unless the information was recorded in careful columns, efforts to decipher these passages will almost surely defeat an amateur,” Hedstrom cautions. Varying penmanship, unorthodox abbreviations and other obstacles abound. “Even professionals feel like they almost can’t decipher these pages. But somehow we always do,” she adds.

With church records, or almost any official documents, always provide more than just the entry about your clan. Send the entire page or copy several pages. This will help the translator learn the characteristics of the writing. “If I’m in doubt about a word,” Oslon says, “I often need to find another letter f or p for comparison.” Chudziak-Kuchinka adds: “Don’t just copy a letter. Show me the envelope, the stamp and the cancellation mark. These may offer surprising clues.”

Genealogical translation starts with words, but in fact the process is much more comprehensive. “Good genealogical translators do far more than translate words,” Hedstrom says. “They can help you to assemble a vital list of contacts in the genealogical community, in Internet newsgroups, as well as abroad.”

Because translators often maintain contacts in their native lands, they can also provide key guidance for your research activities abroad. What’s the best way to access foreign-language records in an Italian town unchanged from medieval days? How should you approach the local mayor or pastor in a rural Polish village? A good translator can often help. “I don’t just understand German,” Hedstrom says. “When it comes to Germany, I understand how things are done there.”

Going above and beyond the call of duty often becomes the norm for these polyglot pros. “I’ll contact the village priest for more information about a town name mentioned in an old letter,” Chudziak-Kuchinka notes. “I’ll even argue with my colleagues about the exact way to translate a word. It’s very important to us.”

Hedstrom agrees: “For me, there is always a personal connection. I’ve helped clients find that local history about the town where their forefathers where born. Don’t you think the village is curious about return of their ancestral son? They will help you in all kinds of ways, if we approach them properly.” Clearly, what begins as “translation” often becomes a total genealogical service.

The same translators who rendered your ancestors’ words into English can help you prepare those all-important letters of inquiry to churches, libraries and town officials in foreign lands. Their knowledge of etiquette can be invaluable. “I can help by writing in Polish letters to Poland,” Chudziak-Kuchinka says. “This can help you in your search for relatives presently living in Poland.” Oslon often interprets Russian and Ukrainian phone calls, sometimes making the phone calls herself.

So now you’re the one who needs your words translated to another language, just as your ancestors did so long ago in their new country. But while they sought to change their Italian, Swedish or Lithuanian into the words of their new land, you’re making the return trip — back to the mother tongue.

Möglicherweise haben Sie Ihre Weise Haupt gefunden.

Perhaps you have found your way home.

Find it on the Web

• Cyndi’s List: Languages and Translations

<www.cyndislist.com/language.htm>: More than 125 links to Web sites on alphabets, foreign language translations, form letters and professional translating services.

• Federation of Eastern European Family History Societies Database of Professional Translators

<feefhs.org/frg/frg-pt.html>: Lists names and contact information for translators who specialize in Eastern European languages.

• Genealogy Pro

<www.genealogypro.com>: Provides translators, historical researchers and other genealogical professionals with expertise in more than 70 nations of origin in Europe, Asia and Africa.

• FreeTranslation.com

<www.freetranslation.com>: Instant machine translation that allows basic comprehension of text.

• Babel Fish

<babelfish.altavista.com>: Translates text and Web sites from English to other languages and vice versa.

• Lexicool

<www.lexicool.com>: Links to any translation dictionary imaginable.

• e-transcriptum

On the bookshelf

• Following the Paper Trail: A Multilingual Translation Guide by Jonathan Shea and William Hoffman (Avotaynu Press): Alphabets and word lists for translating official records in 13 European languages.

• The Genealogist’s Address Book by Elizabeth Petty Bentley (Genealogical Publishing Co.): Lists genealogical societies by country, language and state.

• Translation Guide to Nineteenth Century Polish Language Civil Registration Documents (Jewish Genealogical Society)

• In Their Words: A Genealogist’s Translation Guide to Polish, German, Latin, and Russian Documents, Volume I: Polish by Jonathan D. Shea and William F. Hoffman (Language & Lineage Press)

• German-English Genealogical Dictionary by Ernest Thode (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

• Central European Genealogical Terminology by Jared A. Suess (Everton Publishers): German, Latin, French, Hungarian and Italian terms with English translations.

• Mini Dictionary for Research in Foreign Genealogical Records, Volume I (Everton Publishers): Danish, Dutch, German, Norwegian and Swedish writings with English translation.

From the August 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT