Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

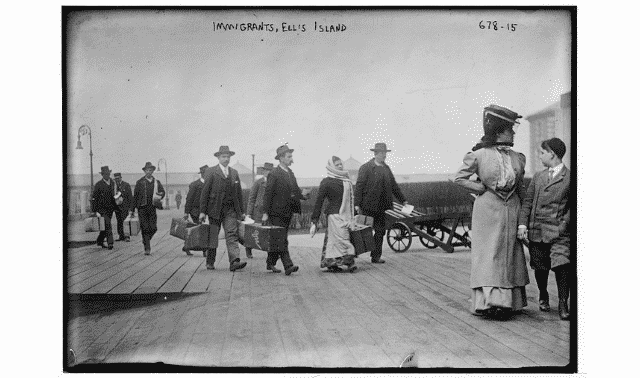

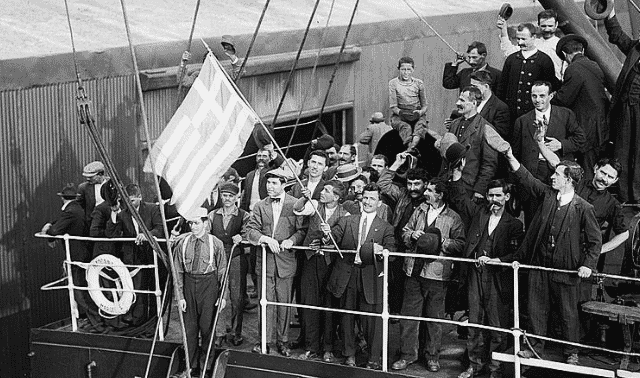

Most genealogists end up doing it at one time or another. We’re talking about crossing the pond, of course. Whether your ancestors sailed over on the Mayflower, sought to escape the Great Famine in Ireland, or helped form the mass migration starting in the late 1880s, your research trail will likely lead you to Europe—not necessarily literally, but definitely mentally.

Of course, the figurative journey back to the old country isn’t always a smooth one. Name changes, confusing geography, and records in unfamiliar languages and formats can easily intimidate even experienced researchers. But don’t let these challenges hold you back. With our 10 tips for tracing your immigrant ancestors from Europe, you’ll sail right through these potentially rough research waters.

1. Look for US Records First

Gather as much information as possible on this side of the ocean before you try to cross it. You’ll want to learn your immigrant ancestor’s hometown in Europe, his original name, and other details to help you identify him in foreign records.

Believe it or not, the best place to begin researching is at home. Talk to your relatives and ask them for copies of family documents such as birth certificates, passports, naturalization records, correspondence, and other papers likely to contain clues to ancestral origins.

Next, search genealogy records. The old standby, the federal census, usually provides only a country of origin. Even immigrant passenger lists can be hit or miss—sometimes they give a village or town; other times, just a province or region. Birth, marriage or death certificates and military papers may have clues. Obituaries may list where an immigrant was born, but because a relative or associate provided the information, it may not be accurate.

Other government records can also provide information about country of origin. In 1917 and 1918, male US citizens and aliens born from 1872 to 1900 had to fill out WWI draft registration cards, searchable online at Ancestry.com and FamilySearch. If the person had a Social Security Number, request his SS-5 (Social Security number application) through the Social Security Administration. (See the SSA’s FOIA guide for more information.)

Keep in mind that immigrants often traveled together and put down roots among relatives and friends, forming “cluster communities.” They ran their own churches and schools, established newspapers and formed social organizations. Don’t overlook repositories specializing in these immigrant communities, such as the Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Immigration History Research Center (IHRC) at the University of Minnesota and the Slovak Institute in Cleveland. An ethnic-based genealogical society might yield even more results.

2. Determine the Immigrant’s Correct Name

It’ll be hard to find your ancestor “William Smith” in Germany if he went by Wilhelm Schmidt there. The names you find in North American records may be Americanized versions of their European equivalents, or altogether different. But don’t buy into the family lore about your ancestor’s name being changed by immigration officials at Ellis Island (or other ports). This simply didn’t happen.

But many immigrants changed their own names once they arrived in America to make the name appear “more American.” Often, they’d change or drop a few letters. For example, the Polish name Jablonski might become Yablonski, or the first name Jan would become John. Or they’d switch to a phonetically similar name (Stanislaw becomes Stanley). Some bosses or teachers called immigrants by names that were easier to spell or say.

Connecting with others researching the name might help you determine its original form. A Google search is a good start, but you might have better luck on a genealogy-oriented site such as Cyndi’s List or RootsWeb’s Surname Resources Page. Whatever the name, search for all conceivable variations and phonetic spellings in indexes and online databases.

3. Study Naming Practices

Studying European cultures’ naming customs can often help to clue you in to previous generations and extend your family tree. They can also be useful in determining siblings’ birth order or determining whether there were other children.

For example, children’s names can give you important clues to likely names of the grandparents. For example:

- In the Italian tradition, the first-born son is named for the paternal grandfather, the first daughter for the paternal grandmother, the second son for the maternal grandfather and the second daughter for the maternal grandmother.

- Carpatho-Rusyns often named the eldest son after the father and the second son after the paternal grandfather. The third son was named after the maternal grandfather. The eldest daughter would be named Mary; the second, Anna; and the third, Helen. Subsequent children would be named after other relatives. This explains why the same given names seemed to be repeated through the generations in many of my own family lines.

Learn how different cultures use patronymics for hints to a father’s first name. In Scandinavian languages, the patronymic surname was formed by adding suffixes to the father’s first name: –son or -sen to indicate “son of”, and –dotter,-dóttir or -datter for “daughter of.” The Spanish use double surnames; when a woman marries, she keeps her last name, and adds her husband’s surname (Maria Pérez Álvarez).

4. Study Social History

Finding out the “why” behind your ancestors’ lives is just as important as the who, what, when and where. Sociologists and historians studying the migratory patterns of humans often refer to “push” and “pull” factors causing such movements.

“Push” factors are conditions that drive people to leave their homelands, such as crop failures, epidemics, scarcity of land, poverty, high taxes, political or religious persecution, obligatory military service and wars. My paternal grandfather left Slovakia before his 17th birthday to escape a mandatory three-year service in the Austro-Hungarian army.

“Pull” factors attract people to a new area, typically providing the potential for social and material betterment. These include the promise of political or religious freedom, or the availability of land or jobs. Perhaps you’ve heard stories about your ancestor’s “hope for a new life” or belief that in America, “the streets are paved with gold.” Sometimes you’ll find several reasons for your ancestors’ immigration decisions.

Creating a timeline with family and historical events can help you see what influenced their decisions. Start with our free biographical outline, or use family-tree builders like Ancestry.com to create profile pages for your ancestor. You also can generate a timeline from your genealogy software.

5. Study Geography

In order to successfully trace an immigrant ancestor, you’ll need the name of his town or village of origin. Usually, just knowing that an ancestor came from Ireland or Germany won’t help you research an ancestor in the old country. And even knowing that an ancestor came from London, Paris, Kiev or some other large city might not be enough.

That’s because in most foreign countries, the majority of records were kept on a local level, in a town hall or parish office. But especially in US sources, immigrants often would give a large city as their place of birth simply because it was a more familiar point of reference.

To know where to look for records, you’ll need to know how boundary changes might’ve affected your family’s town (wars and political moves may have changed its name or the country it was in) and have a working knowledge of historical and current geography.

Most cities, and even smaller towns or villages, have websites. Try a Google search for town or village name (such as Donegal Ireland); add a province or county name if needed. To get more specific, consult gazetteers—these geographical dictionaries list the towns in an area and tell you about political jurisdictions (provinces, counties, districts) and where a town’s inhabitants went to church. For more help putting the place name into context, see Place Names of the World—Europe Historical Context, Meanings and Changes by John Everett-Heath (Palgrave Macmillan).

6. Bypass Foreign-Language Barriers

Don’t expect key records to be in English. The same applies to websites and correspondence. Therefore, you’ll want to learn some basic genealogical terms such as baptism, marriage and death; husband, wife, mother, father, occupations, and so forth. Consult the FamilySearch’s foreign word lists and letter-writing helps. Family Tree Magazine has its own downloadable word lists for German, Czech and Spanish.

For short, rough-but-serviceable translations, try the free online translators available from Google or BabelFish. Just type in a word or block of text, choose from a list of languages and click Translate. Consult a professional for tougher jobs (see No. 10).

7. Find Immigration Records Online

“Crossing the pond” doesn’t mean you have to hop on a plane or ship. Thanks to the Internet, you can make great progress even on your laptop. Explore the free FamilySearch Record Search, the massive, totally free collection of genealogy records compiled and digitized by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS).

Ancestry.com’s World Explorer subscription includes records from the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, France, Sweden and other countries. UK-based Findmypast has hundreds of millions of records, including censuses, military documents and civil registrations. You’ll need to pay for full access; plans range from pay-as-you-go to about $179 a year.

Other subscription sites have records from specific countries or regions. On ScotlandsPeople, search wills and testaments and coats-of-arms databases for free. Viewing record images of wills, statutory registers, old parish registers, censuses and more will cost you on a pay-per-go basis, with cost varying based on record type. Find more online resources at WorldGenWeb and, for the UK and Ireland, GENUKI. Also check the 101 Best Genealogy Websites list for honorees offering records from your ancestor’s home country.

8. Use FHL Collections

FamilySearch is digitizing and indexing many of the records the Family History Library has collected over the decades. But that’s not the full scope of what the FHL and FamilySearch has to offer, since the Family History Library has been a well-known genealogical resource for years. The FamilySearch Research Wiki can tell you what records to look for from your ancestral homeland.

As of 2020, FamilySearch is working to upload images for all the microfilm in FHL’s care. Consult the online catalog to determine what collections have been digitized (and, if you’re lucky, what have been indexed).

Start by searching the catalog by place or keyword, rather an ancestor’s name. The default is place; to search, type in a place and select it from the dropdown to search its standardized name. A keyword search helps get you to a specific record group or topic (for example, 1869 Hungarian Census).

Though you can no longer order microfilm to your local Family History Center, you still may find a nearby center has the record(s) you need. Or you can note microfilm listings to consult on a trip to the FHL in Salt Lake City.

9. Write to Archives

Of course, the FHL doesn’t have all the records for all the countries in the world. Your next move may be to contact archives or churches of the area you’re researching. Knowing where records are located gives you a huge advantage. Check the International Vital Records Handbook, 5th edition, by Thomas Jay Kemp (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

Many archives post research request instructions and fees on their websites. When you make a request, follow the instructions exactly and make your question as specific as possible. Be brief and simple, using short sentences, and ask for records related to only one ancestral line at a time. Give dates European-style—day, month, year—for example, 10 February 1897. Be sure to provide an upper limit for the fee you can pay, if you have one. (See a sample request letter.) You’re more likely to get a response if you compose your letter in the native language.

Responses will vary depending on the archive’s location, facilities and communications protocol. In general, don’t send money or a check with your request unless instructed to do so. Do include a self-addressed business-sized envelope, and at least two international reply coupons (available at your post office) to cover return postage. Not all countries accept them, though, so ask the postal clerk for advice. If you’re writing to a church, include a small donation ($10 or $15) in the form of an international money order. Cyndi’s List links to additional advice for corresponding with an archive.

10. Hire a Professional Genealogist

When you’ve tried all the other avenues and you still can’t get your hands on the records you need, consider hiring a professional researcher based in your ancestral homeland. He or she will be familiar with the area’s geography, history and languages, and will be able to access records available only in person.

This option isn’t cheap, but it may prove the most effective for locating key records overseas. Perhaps a fellow researcher or ethnic-based genealogy society can provide a referral, or check online directories of organizations such as the Association for Professional Genealogists (APG), Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG), International Commission for the Accreditation of Professional Genealogists or ProGenealogists. Ask upfront about the fee schedule, payment terms, expenses and any other costs.

Don’t let a few thousand miles keep you from finding your ancestors. With the right road map and careful planning, you can chart the course for genealogical success.

A version of this article appeared in the January 2010 Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT