Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The home movies of your childhood probably look a lot like those at the beginning of the old Wonder Years TV show: grainy, jumpy, no sound. When Dad wanted to show off the family memories he’d captured, he hauled out a clattering projector and unrolled a balky screen at one end of the living room. Editing home movies meant slicing and splicing.

Today, your family memories can look like they were recorded in Hollywood instead of at home. You can play them — in stereo — on your TV set, or e-mail snippets to Grandma and Grandpa. And you can edit today’s home movies on your computer, adding special effects to rival Star Wars.

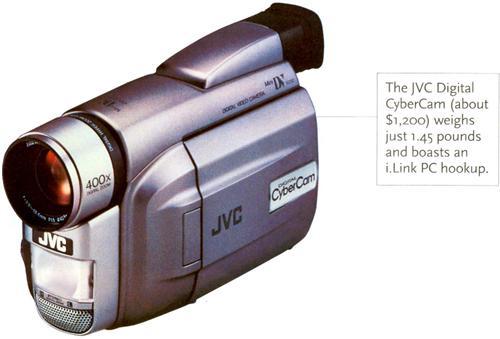

Even if you already own a video “camcorder,” the time may be right to upgrade to state-of-the-art home movies, which these days means digital video. For not much more than you paid for your VHS camcorder five years ago — $700 to $1,400 — you can get a cutting-edge camcorder that stores ultra-clear footage on digital cassettes. Some digital camcorders are compatible with older tape formats, too: If your brother-in-law has a stack of 8-mm cassettes lying around the house, they’ll play fine on one of Sony’s digital cameras, for example.

The digital video revolution promises to do for your home movies what programs like Family Tree Maker have done for your genealogy record-keeping. By turning your memories into digital bits and bytes, this technology makes it easier to record, work with and share your family heritage.

See how digital video compares with the familiar “analog” video:

• Digital video is typically brighter, sharper and more colorful than analog video.

• Digital video is ideal for copying. Because digital camcorders convert images and sound into computer-style 1s and 0s, duplicates look just like the originals. Analog footage looks less sharp when copied, and is prone to distortion.

• Digital video is the most computer-compatible. With the right camera and computer, you can quickly transfer footage on and off your hard drive without loss of quality.

In short, digital is the best option if you can afford it. If you’re on a budget, analog camcorder options abound — we’ll take a look at what’s new here, too. But be warned: Analog cameras account for an ever-smaller slice of the market, and they may go the way of your dad’s home-movie camera sooner than you think.

The incredible shrinking cassettes: DV and MiniDV

If you’ve ever tried using a camcorder that records on standard VHS tapes, you know how cumbersome such a behemoth can be. The latest digital camcorders, by contrast, fit in the palm of your hand.

This is made possible in part by DV and MiniDV cassettes that are smaller than an 8-mm cassette and only a fraction of a VHS tape’s bulk. Yet a DV cassette can hold several hours of footage.

The latest DV-style consumer camcorders use match book-size MiniDV cassettes, which measure only 2.6 inches by 1.9 inches by 0.5 inches. This means cameras can be really small: Canon’s Optura could be mistaken for a professional 35-mm camera. The Canon ZR looks like a compact audiotape recorder. MiniDV tapes hold only about an hour of video, but a 120-minute version may be hitting the market as you read this.

MiniDV camcorders are pricey — -the latest models were introduced at $700 to $1,400. But you’ll get CD-quality sound and imagery that’s at least 25 percent clearer than analog video.

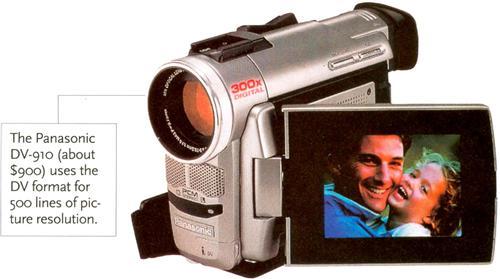

Think of video footage in terms of “lines of resolution,” as in the horizontal lines that make up the pictures on a television screen. A TV has 525 lines of resolution, while DV and MiniDV images have up to 500. Analog video has 400 or fewer.

Bridging both worlds: Digital8

Embracing the latest movie-recording technologies has often meant leaving older formats behind. You can’t use a new MiniDV camcorder to play 8-mm or Hi-8 cassettes, for instance.

But now analog-camcorder users can go digital without relegating your 8mm or Hi-8 tape libraries to your attic. Sony has released a new line of Digitals cameras that play and record on 8mm and Hi-8 cassettes as well as the latest Digitals cassettes. (If you’ve been using VHS or VHS-C tapes, you’re out of luck — but you can always play those on your VCR.)

Digitals camcorders are bulkier than MiniDV cameras, to accommodate the larger cassettes. The DCR-TRV 510, which was Sony’s top-of-the-line Digitals model last summer, has roughly the dimensions of three stacked paperback books but more heft.

Otherwise, Digitals camcorders offer the same benefits as DV and MiniDV cameras, including vivid digital footage with up to 500 horizontal lines of resolution. They also cost roughly the same — about $800 to $1,400 as this article went to press.

Best budget bets: Analog formats

Still want an analog camcorder? OK, making sense of this marker means mastering a confusing array of acronyms: VHS, S-VHS, VHS-C, S-VHS-C, 8mm, Hi-8, Hi-8XR and others. Here are your key choices:

• VHS variants: Some of the first analog camcorders played and recorded on standard VHS cassettes, the same tapes used in a VCR.

• Newer camcorders use a compact version of VHS called VHS-C. Because the cassettes are smaller, the cameras can be more compact. VHS-C cassettes play on your VCR when fitted into an adapter.

• A “super” form of VHS, as in Super VHS and Super VHS-C, improves image quality. S-VHS has up to 400 lines of resolution while VHS and VHS-C have 240 or fewer. Super VHS-C cameras retailed for about $600 at press time.

• 8mm variants: Camcorders that use 8-mm tapes remain plentiful. Such cassette formats range from standard 8mm, which let you record up to two hours on a single tape, to Hi-8 and Hi-8XR.

The latter two are probably your best bet — Hi-8 has up to 400 lines of resolution, while the harder-to-find Hi-8XR has up to 440 lines. Put another way, Hi-8 delivers images that are up to 65 percent clearer than 8mm, and with high-fidelity sound.

Hi-8 cameras retailed for about $600 when this article went to press, while 8mm cameras were available for $400 or less.

Digital do’s

So have we sold you on going digital instead of old-fashioned analog? When you go shopping for a digital camcorder, look for these features that can make your home movies look like Hollywood extravaganzas:

• Zoom and digital zoom: Good camcorders have zoom lenses, plus digital enhancements to get you even closer.

• Optical image stabilizer: If you’re a bit unsteady, this feature makes for smoother, more stable pictures.

• Special effects: Want to get creative? Digital camcorders provide built-in special effects such as “fade” and “wipe.”

• Still images: Get double duty from your camcorder by snapping still pictures as you would with a digital-still camera.

• Enhanced batteries: Camcorders drain batteries quickly. Features such as Sony “Stamina” boost battery life.

• FireWire capability: Digital camcorders have FireWire or “i.Link” ports for transferring footage to PCs or Macs.

• Composite and S-video output: Play your video on your TV or transfer it onto an analog VCR or camcorder.

• Analog line-in: Get footage into your digital camcorder, too. This feature works with TVs, VCRs and analog camcorders.

The computer connection

Because digital footage is made up of computer-style 1s and 0s, it can be moved to your hard drive like any other kind of digital data. Then you can mold your home movies into polished productions that would do Francis Ford Coppola proud.

The latest digital camcorders and some computers have a built-in feature called IEE 1394 or “FireWire” that makes such transfers quick and easy. Look closely at these gizmos and you’ll find oval-shaped FireWire ports. Desktop computers typically have large FireWire ports while camcorders and laptops have small ones. Connecting with a FireWire cable takes all of 10 seconds. Then you simply instruct the computer to yank all that footage of your toddler onto your hard drive, and you’re ready to make magic.

FireWire isn’t the only way to get video into a computer. In some cases, you can use a computer’s Universal Serial Bus port to transfer digital footage. A USB port is similar to a Fire Wire port, but video transfers take more time.

Video-capture cards will also do the trick. These cards fit inside your computer and let you plug in an analog or digital camcorder. This is the best option for those with older cameras and computers that don’t have FireWire.

To better understand how computers and camcorders work together, let’s scrutinize a few PC-camera combos and the software products that turn them into video-editing powerhouses:

Sony computers and camcorders: No one has embraced Fire Wire more fervently than Sony. Don’t use the word “FireWire” around Sony salespeople, though, because the company has coined its own term for the technology, “i.Link.”

Sony has released an entire line of desktop PCs and laptops that incorporate this technology. Its digital camcorders are i.Link-enabled, too. This means the company’s cameras and computers work as a seamless whole. Users of non-Sony camcorders may run into trouble, however.

Notable Sony computers with Fire Wire — er, i.Link — include the VAIO Digital Studio line of desktop PCs and the PictureBook mini-laptop, which has a built-in video camera for creating your own clips.

Sony includes video-manipulation programs with many of its i.Link-equipped computers. This software includes DVGate Motion, a simple program for scanning, splicing and organizing footage, and Video E-mail, a tool for compressing video clips into a format that’s easy to send as e-mail attachments. This software is useful but too simple for some users. Try it, then ponder whether you’ll need a more sophisticated video-editing package.

FireWire Macs and digital video: It’s no surprise that many Macintoshes incorporate FireWire — since Apple Computer invented this technology. The company’s Power Macintosh G4 professional machines and most of the latest iMac consumer machines have built-in FireWire capabilities.

Apple even makes video-editing software. A consumer-oriented program called iMovie comes bundled with FireWire-equipped iMacs, also known as “DV” iMacs.

To make Final Cut Pro really sing, you need a Power Macintosh G4; these machines start at about $ 1,600. You also need a good camcorder such as the Canon Elura, a curved beauty that snuggles in the palm of your hand. Expect to pay $1,000 or more for such a camera.

For those who lack FireWire: Don’t despair — video-editing alternatives abound. Let’s say you have a Pentium PC or a Power Macintosh without FireWire. If the computer is a relatively recent model with ample horsepower, consider getting a FireWire card that installs in a PCI slot and adds FireWire ports. Such upgrade kits are available from ADS Technologies, Digital Origin, Orange Micro, Pinnacle Systems and Siig.

Or, for a non-Fire Wire PC solution, get the Dazzle Digital Video Creator ($250). This external device plugs into a USB or parallel port to capture camcorder video. The Dazzle contraption comes with full-featured video-editing software.

For Power Macs without FireWire, consider Iomega’s Buz Multimedia Producer. This $.300 kit includes an Ultra SCSI controller that fits inside your computer, plus an external device for plugging in a camcorder. Iomega no longer makes a PC Buz.

If you own an iMac without FireWire ports, you can’t install a FireWire or SCSI card because the Mac doesn’t have expansion slots. Avid comes to the rescue: A version of the company’s popular Cinema video-editing software ships with an external video-capture device that plugs into an iMac’s USB port.

Cinema is one of the most consumer-friendly video-editing programs you can buy. It has only a fraction of Final Cut Pro’s capabilities but, at $100 or so, doesn’t induce sticker shock.

Avid makes a Windows version of Cinema, too. To use the software, you’ll need a video-capture card from ATI or one of several other makers. Such boards, which run up to $300, fit into a PCI slot. When buying such a card, make certain it’s compatible with the video-editing software you plan to use. Avid, for instance, is very selective about the cards that operate with its software; as of this writing, Matrox bundled Avid Cinema with its Marvel G200-TV board ($279).

Other affordable and consumer-friendly video-editing programs include Ulead’s VideoStudio and MGI’s Video Wave II, both of which cost about $100. For more professional results, look at Ulead’s MediaStudio Pro and Adobe’s popular Premiere, which run $500 to $600.

Put it all together and the latest digital home movies can make your memories a show your family will line up to watch. The only thing you’ll still have to do the “analog” way is pop the popcorn.

ADVERTISEMENT