Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Those who served in the Civil War faced untold horrors and challenges. Roughly 750,000 troops never returned home. Battlefield doctors chopped off limbs to save lives. Some troops endured extreme neglect in prisoner-of-war camps. For years afterward, survivors suffered permanent disfigurement, lingering illness and psychological damage.

If your ancestor was somewhere in the smoke of the war (which was also called the War Between the States or the War of the Rebellion), you likely want to know more. Where was he? On which battlefields, carrying out what responsibilities? Was he killed, injured or captured? Was he ever promoted (or demoted)? If he survived, what happened to him? Did he collect a pension? Did he continue to suffer physically? What were the lasting effects on his family?

Answers to many of these questions unfold in a variety of historical records. Here, we honor those who served with this 21-resource salute, ranging from common genealogical records to less-familiar military documents. Start your search for ancestors that served with these Civil War records.

Determining Whether Your Ancestor Fought

Neither the Union nor the Confederacy supported large standing armies when the conflict began. The North—also called the Federals—held command of the nation’s small regular army and navy, while the South claimed the arsenals of military installations in Confederate territory. Both sides recruited additional volunteers, instituted drafts, and called upon loyal state militias.

Hodgepodge recruitment resulted in piecemeal record-keeping by each side, as well as within each military branch or militia. The result is that no single collection of historical records can confirm whether your ancestor fought in the Civil War.

However, his circumstances may be telling. If he was born between about 1828 and 1848 and was a US citizen (rendering him eligible for the draft), he likely served. Or if he could afford it, he hired a substitute. (Yes, paid substitutes were legal on both sides—at least for part of the war.)

But these aren’t the only men who served. Resident aliens were not subject to the draft, but not all of them knew that or chose to stay out of the conflict. Thousands of immigrants who hadn’t yet naturalized volunteered or served as paid substitutes, especially on the Union side.

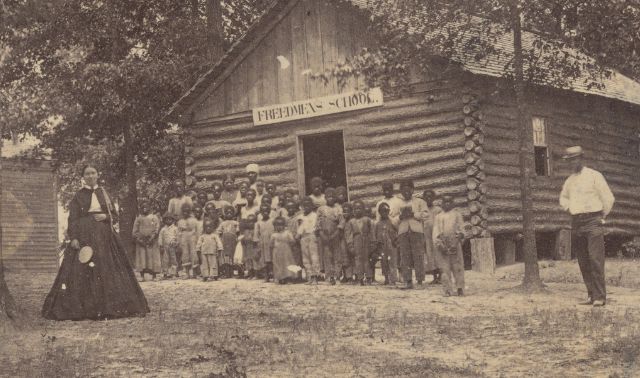

Free men of African heritage could only serve in the US Navy at the war’s outset; eligibility broadened after the US Militia Act of 1862. In 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation declared freedom for enslaved people in the Confederate South, the US Army established the United States Colored Troops, which eventually numbered more than 178,000 men. Regional black militia units also served the Union. On the Confederate side, Black military recruitment was limited almost entirely to non-combatant roles.

Before you rule out any ancestor’s service—or rush off to order military records—look closely at the following resources.

Family stories and artifacts

Maybe you grew up hearing proud tales of the ancestor in Confederate gray or Union blue. Perhaps a cherished military portrait photograph graced a family album or fireplace mantel. If you were lucky, maybe your family had Great-grandpa’s Civil War letters, a belt buckle from his uniform, or other artifacts. Even if you’ve seen no evidence, ask around—maybe another relative has.

Federal census records

Study your family’s entries in the 1860 and 1870 US censuses. Did an adult male disappear from your family? Did children’s births stop when a father would have been away fighting?

Next, check the 1890 schedule of Union veterans and widows. It survives for about half the country and includes some Confederate names. The 1910, 1930 and 1940 censuses also asked about past military service. (In 1940, this was only in the supplemental questions that were asked of a small minority of participants.) The 1950 census also asked about military service, but only a handful of Civil War veterans were still alive at the time.

You can find US censuses, including the 1890 veterans schedule, on most major genealogy websites.

State and territorial censuses

States also took their own censuses, and sometimes asked about military service. The New York State census of 1865, for example, enumerated men who had or were currently serving in the “present war.” Later Minnesota censuses of 1885, 1895 and 1905 asked about participation. Alabama took censuses of surviving Confederate veterans intermittently beginning in 1907.

Obituaries and death notices

Newspapers may have reported a serviceman’s death in papers local to the deceased or his distant loved ones. For decades following the war, obituaries of veterans proudly proclaimed their service to the Union or Confederacy.

Tombstone inscriptions and databases

Gravestone inscriptions, icons and even the shape of the stones can all hint at military service. Burial in a military cemetery or with military honors—which you may discover in a burial database—is also a good clue.

Soldiers and Sailors database

Millions of Confederate and Union servicemen appear in the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System database. To date, entries of Army soldiers are most complete. The sailors’ listings include about 18,000 African Americans on the Union side. While not comprehensive, this is a great place to start searching for Civil War ancestors.

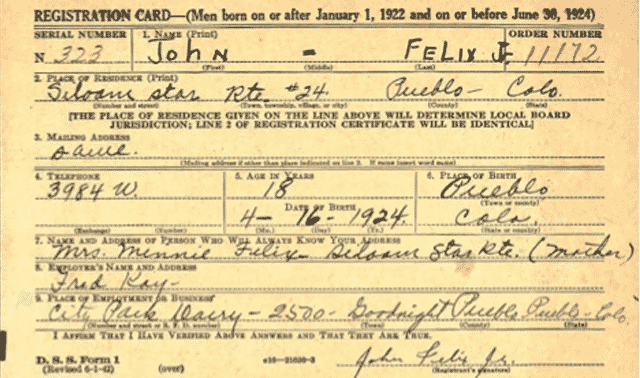

Draft registrations

Civil War-era draft registrations exist in some places, but they won’t indicate whether a man actually served. You can find some Union draft records online at Ancestry.com, but you’ll need to research surviving Confederate records (as well as additional Union documentation) at the National Archives.

Researching Civil War Service Records

Once you’ve established a relative served, you can access several kinds of records to learn about his service. You can even determine what action his regiment would have seen.

But before explaining where to find records, we should stress a distinction among Civil War servicemen. As mentioned earlier, a small number of “regulars” were career military at the time of the Civil War—their service wouldn’t have begun or ended due to the war.

But the vast majority of Civil War servicemen joined just for the duration of the war and were considered “volunteers”—whether they actually enlisted of their own accord or were drafted. It’s important to note the difference, because records of volunteers and regulars were kept differently.

The vast majority of Civil War servicemen joined just for the duration of the war and were considered “volunteers”—whether they actually enlisted of their own accord or were drafted.

CMSRs

Individual Civil War service details are buried in a bewildering variety of enlistments, muster rolls, furloughs, hospital rolls, prisoner-of-war records, medical records and other official documents. Fortunately, for volunteer (i.e., non-career military) forces, these were eventually indexed and organized into individual compiled military service records (CMSR). This effort was so thorough that, in most cases, you can just look for your ancestor’s CMSR—you don’t need to track down all those original documents.

While not known as strong sources of genealogical information, CMSRs are the go-to resource for revealing your ancestors’ wartime experience. They can tell you where your ancestor was, what he was doing, and when he was absent from his command. You may learn about his assignments to specific units, promotions and demotions, injuries, and whether he was a prisoner of war. You may even find a statement of substitute, if your ancestor was hired to fill someone else’s shoes in the ranks.

Both Confederate and Union CMSRs are available. Confederate CMSRs have been digitized on subscription site Fold3. Search within individual state collections and also in separate collections for officers, Confederate government employees, and former Confederates (“Galvanized Yankees”). A miscellaneous collection of unfiled Confederate papers—sorted by surname but never actually deposited into CMSRs—is also searchable on Fold3 and FamilySearch.

CMSRs for Union volunteer Army troops are indexed on Ancestry.com; Fold3 has fuller collections for several states and the United States Colored Troops. (The latter may also include emancipation records, which would reveal the identity of a former enslaver.) Compiled service records for other states—and comparable record collections for other military branches—may need to be researched at the National Archives. Explore instructions for ordering copies on the NATF-86 form.

You may find yourself somewhat lost as you begin paging through CMSRs. They aren’t always self-explanatory; they weren’t written with a public audience in mind. Consult a guide such as Trevor Plante’s Military Service Records at the National Archives, downloadable for free at HathiTrust.

What if your ancestor was an Army regular? You won’t be looking for CMSRs. Rather, turn first to the Army registers of enlistments at both Ancestry.com and FamilySearch. If you find an enlistee, follow up in scattered collections on Ancestry.com. (Under Search > Catalog, enter the keywords regular army.) Then explore additional manuscripts at the National Archives.

Other branches of the military kept comparable records of service. Look for US Navy rendezvous reports on Fold3 and FamilySearch, and Marine Corps muster rolls on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch. Research more records for these branches—as well as original shipping articles and payroll records for the Revenue Cutter Service (forerunner of the Coast Guard)—at the National Archives.

The Ainsworth List

This collection summarizes every federal unit from the Revolutionary War to the end of the 1800s. Details of Union regiments (broken down into companies) include mustering dates and places, commanding officers and regiment size. Find a digitized version in the FamilySearch Catalog.

Dyer’s Compendium

The first of three volumes in this series describes the organization of the federal armies into brigades, divisions, corps and so on. Second is a chronological listing of battles and skirmishes, with participating units. Volume 3 traces the lineage of regiments; look one up by state to see when it was organized, commands to which it was attached, a service record of campaigns, and casualty statistics.

Consult A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion by Frederick H. Dyer (Sagamore Press) for free at HathiTrust. Or go back to the regimental histories summarized on the Soldiers and Sailors database, which references Dyer’s Compendium.

Record of event cards

Available for both sides of the conflict, these handwritten cards document individual events for each company—such as where it was stationed or fighting—intermittently throughout the war. This is a more advanced resource for those who want to dig deeply, since you’ll have to consult them in-person at the National Archives.

Official Record (OR)

OR and ORN (for the Navy) refer to compiled collections of original, significant documents created during the course of the war, such as military orders and correspondence. Consult these via Cornell University’s online portal, Making of America.

Regimental histories

Some military units have had their histories recorded in dedicated works. Search for these in your web browser or in WorldCat. Or ask reference librarians at major research libraries to help you locate them, perhaps via bibliographic works such as United States Army Unit and Organizational Histories: A Bibliography by James T. Controvich (Scarecrow Press).

Images

Photographers were practicing widely by the Civil War, creating resources for those studying both individual servicemen and historical context. Get access to one of the largest collections for individual images from the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center in Carlisle, Penn. Try a keyword search for a battle or unit name, and watch for images in your results. Two other great sources for discovering Civil War-era images are catalogs of the National Archives and the Library of Congress.

Accessing Post-Service Records

Those wartime records don’t generally tell you what happened after the guns finally ceased. Even if your ancestor didn’t survive, you can still explore the aftermath in burial and pension records. Additional records help you follow veterans’ families over succeeding decades.

Union pension records

These are perhaps the single most important genealogical resource for Civil War veterans. That’s because pension applicants—both veterans and their qualifying beneficiaries—had to provide evidence for their claims.

Early in the war, the federal government authorized pensions for the Union Army, Navy and Marine service. Federal pension files generally include the claimant’s declaration; a confirmation of service by the War or Navy department; and any number of affidavits submitted in support of a claim. You may find personal and family-history questionnaires with family identities and relationships. Medical records, especially pertaining to post-war physical disabilities, are part of pension records, too. Pension packets can easily exceed 100 pages.

Search among nearly 2.5 million applicants in the Civil War Pension Index, available at FamilySearch and subscription sites Ancestry.com and Fold3. Indexed entries point to card images summarizing the serviceman’s dependents and service history. If you find an entry for your ancestor, use the same National Archives link (and the form NATF-85) to order a copy of the pension application file.

If your ancestor’s pension is instead at the National Personnel Record Center in St. Louis, the National Archives will provide you with instructions to order from there instead. (This especially applies to long-lived ancestors and those who applied long for benefits long after the conflict.)

Confederate pension records

Confederate pensions were implemented by individual Southern and border states years (even decades) after the war. Pensions were paid out by the state in which Confederate veterans resided at the time they applied. Pensions were only granted to veterans or widows who could demonstrate financial hardship and sometimes physical disability. Unfortunately, except in Mississippi, African Americans were excluded from pension benefits until 1921, by which time most of those who were eligible had died.

A growing number of state Confederate pension collections are available at FamilySearch. Search the FamilySearch Catalog at the state and county levels for entries that may include links to digitized images. Otherwise, ask about Confederate pension records at state archives. (Unlike Union pension records, Confederate pensions are not held at the National Archives.)

Veterans Administration pension payment cards

These are a related resource for Union veterans and dependents. For the years 1907 to 1933, you can look up surviving veterans or widows and learn the veteran’s unit, death dates of beneficiaries, quarterly payment history (look on the back) and when the pension was dropped. Search this collection at FamilySearch and subscription sites Fold3 and Findmypast.

Veterans organizations

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a social organization created for Union veterans after the war. It eventually encompassed Ladies of the GAR and the Woman’s Relief Corps, and dissolved in 1956. A comparable group in the South was the United Confederate Veterans organization, active 1889 to 1951.

Records of local posts for both sides were never centralized. Visit the GAR Records Project for a catalog of known local records. Search for any digitized records online at sources like the Internet Archive. Use ArchiveGRID, an enormous online catalog of archival resources, to locate original manuscript collections, or contact state archives or libraries to ask about them.

Soldiers’ homes

Your elderly, disabled and/or indigent Civil War veteran may have ended up in a federal or state soldiers’ home. Find clues in a pension file, or notice whether a veteran outlived his natural caregivers. Start your search in an Ancestry.com collection of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers records, and pursue originals at the National Archives. Ask about records for state homes at state historical or genealogical societies, or search ArchiveGRID.

Military burials databases

An ancestor’s final resting place may provide confirmation of his Civil War service—and more. Explore Civil War burials in national cemeteries at the National Park Service or the National Gravesite Locator. The Confederate Graves Registry now documents more than 160,000 burials in 47 states. Or search the National Graves Registration Project for Union burials and accompanying biographical details and GAR membership information (if relevant). Yet another collection, available at both FamilySearch and Ancestry.com, includes headstones provided for deceased Union veterans.

Lineage societies

Groups that preserve the memories of Civil War heroes may help you learn more about your ancestors and celebrate their legacies, such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of Confederate Veterans. The latter offers basic genealogy assistance (under the Contact tab). Explore the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War website for resources that might help you research a Union forebear.

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2021 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT