Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Family letters, journals and diaries are precious, one-of-a-kind documents. However, these items often need a bit of editing to make them more accessible and easier for living family members to understand and enjoy.

Say you’ve located a precious family document. Of course, you want to preserve, protect and

share your find with loved ones. But you might want to edit it before passing along to others. That might seem counter-intuitive: Why would you want to change a snapshot in time—a voice from the past?

For some documents, you won’t. A short love letter between your grandparents is probably

perfect as it is.

But what about your grandparents’ privacy? Are there parts of their letters they might not have

wanted to be shared? Or maybe your less genealogically inclined family members would be put

off by the letter’s unfamiliar grammar, length, hard-to-read handwriting or obscure references to

other relatives.

Editing can help loved ones appreciate these missives from the past. Here’s how to turn your family’s journals and letters into a narrative fit for the whole family.

Transcribe the Original Document

To begin, scan the document (if you haven’t already) and transcribe. Though daunting, an exact, word-for-word record provides a digital canvas for any annotating or editing you decide to do later.

Transcription also eliminates legibility issues, giving you a version to share with fellow family historians. You can still also present them with an image of the original document.

You don’t have to transcribe the materials yourself, however. You can let text- or voice-recognition software do the heavy lifting for you. Optical character recognition (OCR), which “reads” an image file and converts non-text formats into text, continues to improve, examining shapes and patterns in images with greater accuracy.

Even just a few years ago, OCR software was too expensive for the average family historian. But most of us already have access to a version of it today. Many scanners come equipped with OCR, and programs like Microsoft OneNote , Google Drive and Adobe Acrobat Pro have built-in text-recognition programs. In fact, Google Docs can “read” most of my Aunt Ann’s handwriting from nearly 25 years ago—even a lot better than my 20-something sons can do.

You can also read the documents aloud, then use voice-recognition or “dictation” software to “type” it out for you. Google Docs and both Apple and Windows devices have dictation functionality. The result won’t be perfect, but it makes transcribing less intimidating.

Of course, if you’re not comfortable learning new software, there’s nothing wrong with simply transcribing family documents into your favorite word-processing program. Remember to keep the digital files for future use even after you’ve printed your final project.

Whatever technology you use, make backups of your work. Save your digital “original” in a separate folder so no one can accidentally overwrite it, and create a working copy for editing.

Determine Your Editing Goals

Family historians edit family papers for a variety of reasons. Preserving a document as-is safeguards our family history. But widening the audience of family members (and the general public) who may read it also helps keep its legacy alive.

You have several options for how to re-produce a family journal or letter, ranging from copying as-is to extensive editing. Below are some different options, organized from least- to most-involved. These are not mutually exclusive, and you could select an editing method:

- Original text as-is, scanned and/or transcribed

- Original text as-is with added footnotes and annotations that provide clarifications and context

- Edited text: Possible changes include removing irrelevant details, cleaning up language, and formatting text to be more reader-friendly

- New text, written by you and quoting the original piece as a firsthand source

Editing Your Family Narratives

The easier the document is to read, understand and appreciate, the larger its potential readership. Think about ways that editing can make the narrative easier to comprehend, digest and enjoy. Here are some ways you might do so.

Annotating Text with Relationships

We often think of editing in terms of a teacher’s red pen. But editing can also include adding information.

Clarify family relationships in sidebars or notes next to your text, which can be especially helpful if the same names repeat through multiple generations. You might even include a full family tree that readers in an appendix can reference, with snippets alongside text so readers don’t have to flip back and forth.

Providing Context

“Editorializing” has a negative connotation, implying that an author strays from historical fact. But adding socio-historical, familial, and emotional context through editing is crucial to properly conveying historical documents and narratives.

Because they’ve done so much of this research already, family historians can add valuable background information to narratives. Was there a family rift that preceded the correspondence? Or was it written amidst a war, pandemic, or economic depression? We want readers to fall into the text and see the world through their family members’ eyes. Adding a little context to old documents can do that for them.

In a similar vein, if you stumble upon historical inaccuracies, you can provide corrections and your source. To preserve the original text, insert your explanation in brackets or an italicized editor’s note.

My mom transcribed her mother’s journals. I don’t think she struck a single word (Grandma wasn’t loquacious), but she did annotate stories with her own memories and backstories. A lifelong social worker and advocate, Mom provided important family information through those notes. They didn’t interfere with my grandmother’s stories, but instead gave them context that made them richer.

Making Text Easier to Read

Writing styles have changed over the decades, and our ancestors had a different relationship with standard spelling and grammar than we do today. To make a text more digestible to a modern audience, consider:

- Correcting spelling and grammar mistakes or inconsistencies, including standardizing place names

- Breaking up long paragraphs

- Adding “white space” that gives your readers a reprieve and helps them better understand the piece’s structure

- In addition, you may run into specific requirements for length, punctuation and style if you’re submitting for publication.

Removing Irrelevant Details

Your goal should be creating an impactful narrative, not necessarily reproducing a facsimile of your ancestor’s writing. That may mean you have to make decisions about what details stay, and which are left out because they distract from the main narrative.

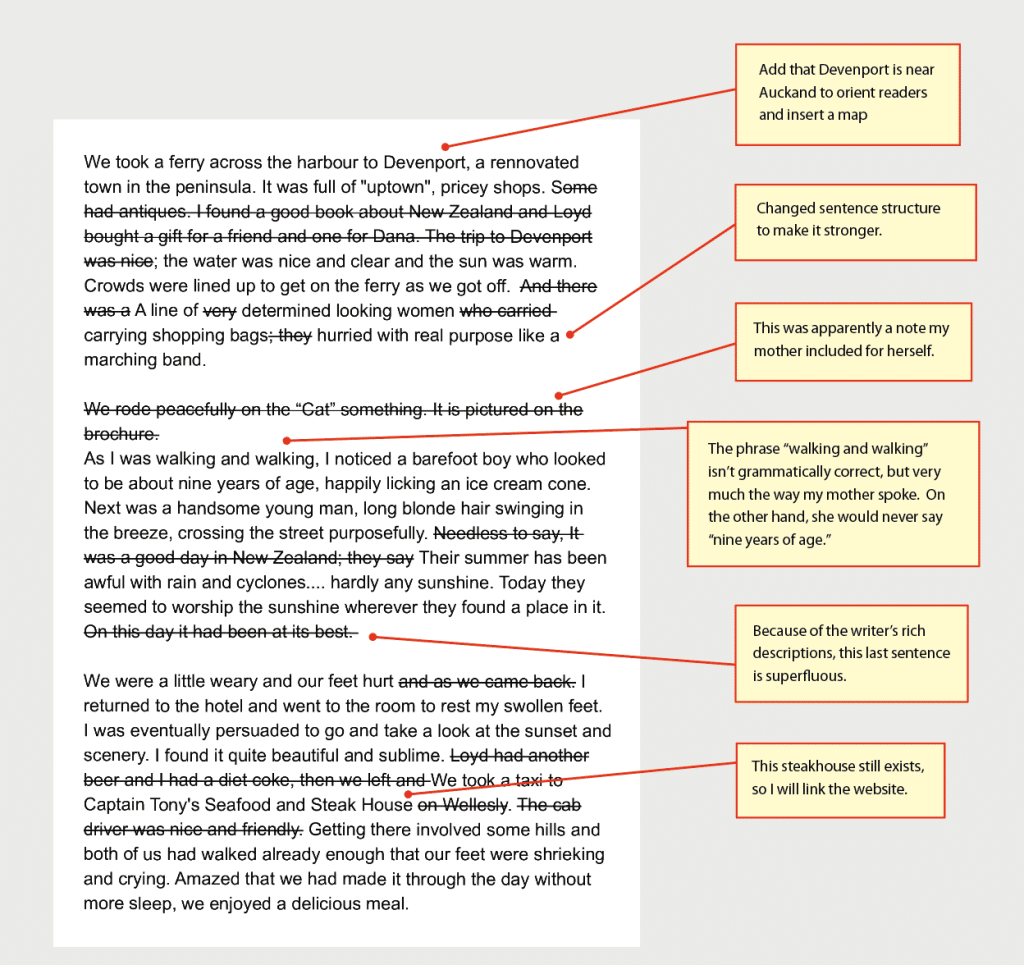

My mother kept travel journals, primarily for herself. She wanted to remember the names of restaurants, what she ate, and if the food was good or not. Twenty-five years later, that minutiae can pull readers out of her stories. The readers begin to skim over those sections, missing the vivid descriptions and slices-of-life she observed on her adventures. See the example above for how I approached editing the journal entry.

Maintaining the Writer’s Voice

A large part of the charm of family documents is hearing the “voice” of loved ones. That voice encompasses more than just the sounds emanating from someone’s throat. In a 2019 article in The New York Times, author Katherine Schulten explains that “A writer’s voice is the way his or her personality comes through on the page, via everything from word choice and sentence structure to tone and punctuation.”

In other words, voice is the character that comes through writing. When that sense of your family member’s character doesn’t resonate, your editing has gone too far. Preserving the original writer’s voice may require you to let a couple of awkwardly worded sentences go if that sentence structure was typical of the way the person expressed themselves. Of course, you want to correct glaring issues or wordiness that try even the most patient reader. But your goal will be to balance personality and flare with the rules of grammar and readability.

One way to accomplish this is to make your edits in phases and save your documents as versions. Give your brain time to process things and then go back and compare the original to your edited version. Does the narrative flow without dragging? Can you still “feel” your family members’ personality? If you decide you’ve taken too much out, you can re-insert text you deleted.

A critique or writing partner can also be a great asset. Have them read both the original and edited versions. Do they still “hear” the original writer through your edits? Do they still stumble over awkward phrasing?

Example: Editing a Journal Entry

Here is a 327-word excerpt from my mom’s journal of her 1997 trip with my dad to New Zealand. Since my sisters and my children don’t remember their grandparents, my editing goal was more about revealing personality than documenting travel locations. The journal is long, and many of my edits were to shorten the length and focus on details relevant to a modern reader. You’ll see my comments to the right.

The final version (183 words) reads:

We were weary and our feet hurt. I went to the hotel room to rest my swollen feet. Eventually, I was persuaded to take a look at the sunset and scenery. I found it quite beautiful and sublime. We took a taxi to Captain Tony’s Seafood and Steak House. Getting there involved some hills and both of our feet were shrieking and crying. Amazed that we had made it through the day without more sleep, we enjoyed a delicious meal.

The Ethics of Family Narratives

Editorial decisions aren’t always straightforward. Though genealogy standards encourage us to protect living people, we face more of a quandary when we think about protecting our ancestors.

Perhaps a letter from one sister to another mentions her husband’s snoring. That’s an innocent-enough complaint in private, but the author presumably never meant to air it publicly. Do you include it because it’s relatable? Or do you prioritize your ancestors’ sense of privacy? Family pressure can also play a factor if certain members insist on a different, more-positive narrative.

As amateur editors, we need to be cognizant of the power we have in making strikeouts. You don’t want to edit the truth out of a family narrative—omitting anything that isn’t “Leave-it-to-Beaver”-worthy is a slippery slope.

In other cases, manuscripts might use language modern readers would find offensive. Deleting or replacing those words could change the historical and cultural accuracy of the text, or perhaps the terminology didn’t have the same connotation at the time the document was written. You could use an abbreviation that readers would immediately recognize as a stand-in for such a word, or include a note that explains the context or your reasoning.

Future descendants certainly want to read sweet or heroic stories. But they also need to be able to imagine knowing their ancestors. How will they connect with their family history if we leave all sensitive topics in the box at the back of the closet? One way to approach whether or not to include a detail or anecdote is by asking yourself if the narrative is as strong without it. Author Annette Gendler considers how to handle decisions like this in her article for Family Tree Magazine.

Sharing Reconstructed Narratives

The last step to this labor of love is sharing the documents you’ve edited. Close family members will want copies, but the wider family history community may also be interested in reading these viewpoints from the past. You could consider publishing the edited narrative through online booksellers, such as Amazon or blogging a journal or letters in smaller segments.

Remember, first impressions matter as readers skim a book or document. (Have you ever thumbed through a book, then quickly put it down due to dense text, small fonts, or a cluttered layout?) Making a page of text more visually appealing not only draws readers into the narrative, but helps them better understand and absorb information.

Here are some ways to organize text so it’s more digestible:

- Add white space

- Use headings and subheadings to convey structure

- Use standard margins

- Break up long paragraphs

- Choose an easy-to-read font at 12-point size or larger

- Use bold and italics sparingly

- Insert historical photos or maps (with appropriate permissions)

- Create graphics like family trees

You can also use excerpts of family documents in other family history writing projects. For instance, you could insert a quote from a firsthand account to bring depth and detail to a historical narrative. In biographical sketches, small quotes that encapsulate your family member’s personality can help readers envision them.

Hopefully, you’ll find the process of editing, rewarding. It allows you to step back in time and grasp not only your family member’s situation, but their personality.

A version of this article ran in the Nov/Dec 2023 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT